On August 23, 1954, 70 years ago, a new era in aviation began when Lockheed test pilots Stan Beltz and Roy Wimmer, accompanied by flight engineers Jack Real and Dick Stanton, embarked on a historic flight.

The YC-130 prototype, which would later become the iconic C-130 Hercules, took off from Burbank, California, and soared into the skies towards Edwards Air Force Base, located about 50 miles to the east.

What made this maiden voyage extraordinary was its takeoff, achieved in just 855 feet of runway—remarkably short compared to the 5,000 feet typically required by aircraft of similar size.

This brief yet impactful takeoff was a precursor to the many feats the C-130 Hercules would accomplish over the next seven decades.

Since that historic flight, the Hercules has been a reliable workhorse for militaries and humanitarian missions globally, delivering troops, equipment, and life-saving supplies to some of the planet’s most challenging and remote locations.

From the scorching deserts of the Middle East to the dense jungles of Southeast Asia, from the icy terrains of Antarctica and Greenland to various other global hotspots, the C-130 has consistently proven its ability to operate in diverse and demanding conditions.

One feature that has helped establish the C-130’s lasting legacy is its ability to take off and land on short, unpaved dirt runways. This aircraft’s versatility and reliability have made it one of the longest continually produced aircraft in history, with over 2,500 airframes delivered to 70 countries.

The aircraft officially entered active service in 1956, primarily taking on the tactical airlift mission for the United States Air Force. With a range of 2,500 miles and a top speed of 380 mph, the Hercules can transport up to 92 combat troops with their gear or 42,000 pounds of cargo.

On August 23, 2024, members of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s C-130 Program Office marked the 70th anniversary of the C-130’s first flight with a commemorative group photo alongside an AC-130A Spectre Gunship at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

The AC-130A, one of the 28 C-130s transformed into side-firing gunships by the 4950th Test Wing’s Aircraft Modification Division in the 1960s, exemplifies just one of the numerous roles this adaptable aircraft has fulfilled.

Over its service life, the Hercules has taken on a range of missions beyond airlifting troops and cargo. It has performed radar weather mapping, mid-air space capsule recovery, search and rescue, aeromedical evacuation, aerial spray missions, firefighting, drone launching, helicopter mid-air refueling, and hurricane tracking.

The aircraft has also supported scientific research at the North and South Poles, proving that its adaptability and reliability are second to none.

1958 C-130 Shootdown Incident

The impressive legacy of the C-130 Hercules over the past 70 years stands as a testament to its groundbreaking design and enduring influence on the aviation industry. However, the C-130’s heritage is not without blemishes.

A significant event in history is the 1958 C-130 shootdown incident, where an American C-130A-II-LM reconnaissance aircraft was accidentally shot down by four Soviet MiG-17s after it inadvertently crossed into Soviet airspace while conducting a mission in the vicinity of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The incident highlights the high-stakes nature of the Cold War, a period marked by intense rivalry and espionage between the United States and the Soviet Union.

After World War II, the Soviet Union, once a crucial ally, quickly evolved into a formidable adversary of the United States.

The closed nature of Soviet society made it nearly impossible for US leaders to gauge the full extent of the Soviet threat. To overcome this challenge, the United States engaged in a variety of intelligence operations, many of which involved aerial reconnaissance.

The Cold War, though largely devoid of direct military confrontation between the superpowers, frequently saw tension flare up in proxy conflicts such as those in Korea and Vietnam.

Despite the presence of nuclear weapons, which both sides were reluctant to use, the Cold War often turned “hot” in these regional skirmishes. In this tense atmosphere, the US and the Soviet Union constantly probed each other’s military, political, and diplomatic strengths and weaknesses.

Information was paramount in the battle for supremacy. Aerial reconnaissance became a crucial tool for gathering intelligence on Soviet capabilities. These dangerous missions involved a range of aircraft skirting the borders of the USSR to collect photographic and signal intelligence.

The unarmed and vulnerable planes needed to fly close enough to collect the required data while steering clear of Soviet airspace.

Soviet fighters, however, were always on the lookout for such aircraft, seizing every opportunity to shoot them down. On the early morning of September 2, 1958, a crew from the 7406th Support Squadron prepared for what they believed would be a routine reconnaissance flight along the Turkish-Armenian border.

Although the squadron was based at Rhein-Main Air Base in Germany, it was temporarily stationed in Incirlik, Turkey, for this mission. The crew of flight 60528 was diverse, ranging from Master Sergeant Petrochilos, a seasoned World War II veteran, to Airmen Bourg and Moore, who were beginning their military careers.

The flight plan called for the aircraft to fly a racetrack pattern between Van and Trabzon in Turkey, ensuring it stayed at least 100 miles away from Soviet airspace. However, shortly after takeoff, at 11:21 a.m. local time, the aircraft veered off course.

The last communication from the crew came at 12:42 p.m. when co-pilot Captain John Simpson radioed Ankara control to report that they had reached Trabzon. That transmission was the final message from the ill-fated flight, which tragically never returned.

What Do We Know About The Shootdown?

The reasons behind the 1958 shootdown of a C-130 Hercules remain a mystery even after all these decades. Some theories suggest that the crew may have misinterpreted a radio beacon, leading them inadvertently into Soviet airspace.

Others propose that the crew might have deliberately strayed from their flight path in an unsanctioned attempt to gather intelligence. Alternatively, the mission could have been officially authorized to test Soviet air defenses.

However, these ideas are purely speculative, as no definitive evidence has surfaced to clarify the circumstances.

What is known for certain is that the C-130 was intercepted by four Soviet MiG-17 fighter jets from the 236th Fighter Air Division. Shortly after 1:00 p.m., the aircraft crossed into Soviet territory and was promptly engaged.

Without even having time to issue a Mayday call, the aircraft was attacked, resulting in the deaths of all 17 crew members, most of whom were in their late teens or early twenties, as described by Larry Tart in his book, The Price of Vigilance.

Unlike other Cold War incidents where American aircraft went down over international waters, this C-130 crashed on Soviet soil. The US government, hesitant to acknowledge that the aircraft was on a reconnaissance mission, initially did not confront the Soviet Union.

It wasn’t until September 6, four days after the shootdown, that the U.S. sought information from the Soviets, who denied any knowledge of the event.

On September 12, the Soviets acknowledged finding a destroyed aircraft and stated that, based on the remains found, it could be assumed that six crew members had died.

When the US demanded details regarding the eleven missing crew members, the Soviet response on September 19 was vague, claiming that no further information about the crew was available.

The situation remained unresolved, with the Soviets providing no additional details about the missing airmen. It was not until 1991, under Russian President Boris Yeltsin, that more information about the incident began to be released.

A major source of new insights came from a joint American-Russian commission on MIA/POW (Missing in Action/Prisoner of War) issues, established in 1992. This commission obtained several declassified reports from Soviet Air Defense Command archives, shedding light on the shootdown of the C-130.

According to a detailed report dated September 4, 1958, sent from Armenia to the Kremlin, Soviet MiGs intercepted and shot down the C-130, which bore the tail number 60528 and belonged to the 7406th Support Squadron.

F-16s “Sitting Ducks” For Russian MiG-31 Fighters? Putin Warns Of Consequences Over Fighting Falcons

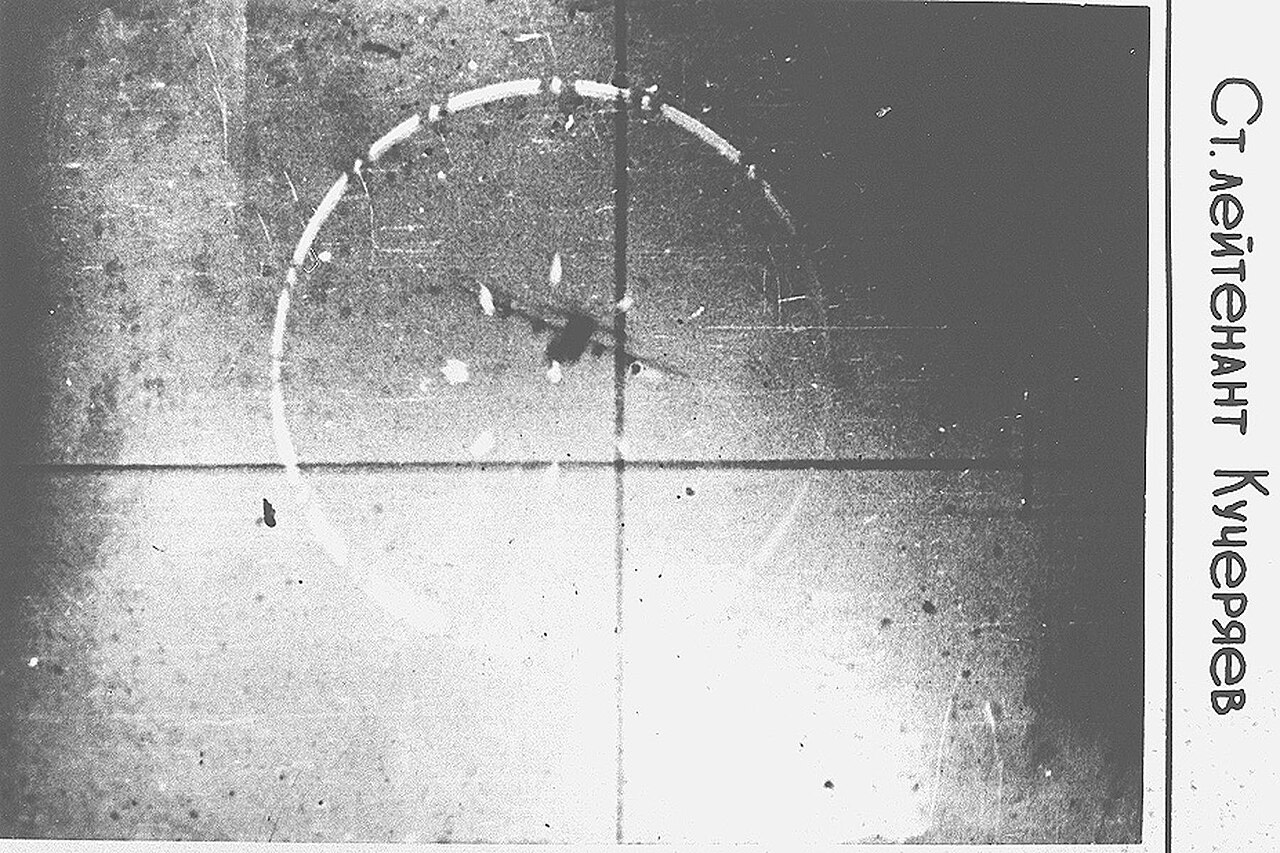

The report documented the aerial engagement, named the four MiG pilots involved, and included gun-camera photos showing the C-130 in the MiGs’ gunsights, with smoke billowing from its engines moments before the crash.

The report also confirmed that only six sets of human remains were identifiable due to the severity of the post-crash fire and noted that no parachutes were seen, indicating that no one survived the crash.

What Happened To Others?

In 1993, a US Army excavation team was sent to Armenia, where they located the remains of soldiers. The remains were subsequently returned to the United States and interred together at Arlington National Cemetery.

The team recovered an identification “dog” tag at the crash site, which belonged to A2C Archie Bourg, an airborne maintenance technician from the USAFSS aboard aircraft 60528 when it went down.

In 1993, Armenian sculptor Martin Kakosian, with the support of local villagers, unveiled a khachkar—a traditional Armenian cross-stone—at the site of the aircraft crash in the village of Nerkin Sasnashen.

Kakosian, who had witnessed the crash as a college student during a field trip in 1958, played a pivotal role in this commemoration. The khachkar, symbolizing a solemn tribute to those lost, initially stood at the crash site but eventually fell and cracked.

Later, a joint US-Armenian memorial was constructed to honor the site and those who perished. In 2011, acknowledging the villagers’ efforts to commemorate the fallen soldiers, the US Army Office of Defense Cooperation renovated the village kindergarten.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News