The Vietnam War was a theater of intense aerial combat, where United States Air Force (USAF) pilots often found themselves facing deadly anti-aircraft missiles.

Among the many stories of courage that emerged from this conflict, Pardo’s Push stands out as a remarkable display of camaraderie and ingenuity.

On March 10, 1967, Captain Bob Pardo, flying a damaged F-4 Phantom II, performed an unprecedented maneuver to push his wingman’s crippled aircraft out of enemy airspace, saving both pilots from certain capture or death.

Robert “Bob” Pardo was born in 1934 in Herne, Texas. From a young age, he aspired to become a pilot, fascinated by aviation and fighter jets. He pursued his education at Texas A&M University, but his true passion lay in flying.

At the age of 19, he joined the U.S. Air Force, determined to fulfill his dream of becoming a fighter pilot. After completing flight school, he went on to fly the F-4 Phantom II, logging 132 combat missions during the Vietnam War.

Vietnam War & F-4 Phantom

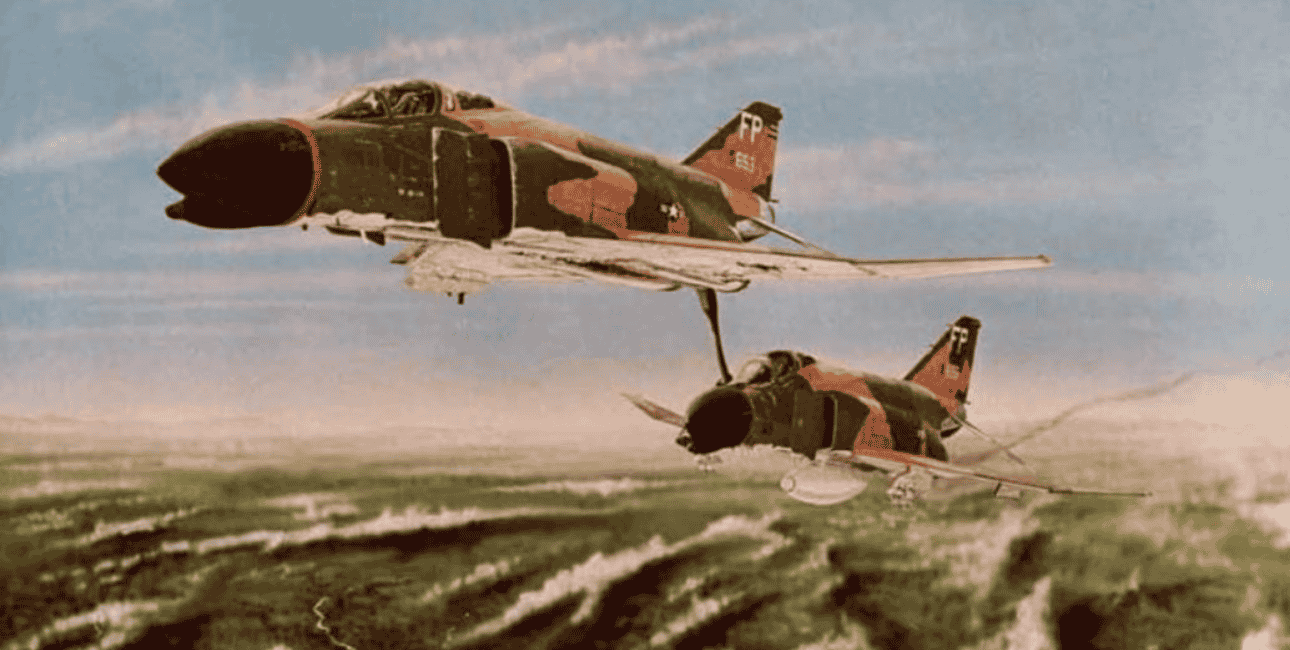

By 1967, the United States was deeply involved in the Vietnam War, relying heavily on air power to strike North Vietnamese targets. The F-4 Phantom II, a twin-engine, two-seat supersonic fighter bomber, was the cornerstone of the U.S. Air Force.

Its speed, firepower, and versatility made it highly effective, yet it remained vulnerable to North Vietnam’s formidable air defenses.

The F-4 Phantom II was equipped with Pratt & Whitney J79 engines, allowing it to reach speeds of over Mach 2. Its advanced radar and weapons systems enabled it to engage targets at a distance, but its lack of a gun (in early variants) made close dogfights challenging.

The country’s dense network of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), and MiG fighter jets made every mission a dangerous gamble.

On March 10, a squadron of F-4 Phantoms was assigned to attack a steel mill in North Vietnam, a heavily fortified target. Among them were Captain Bob Pardo and his wingman, Captain Earl Aman, each accompanied by their weapons systems officers (WSOs), Steve Wayne and Robert Houghton.

As they approached their objective, enemy fire intensified. Both aircraft were hit, but Aman’s jet suffered critical damage to its fuel tanks. Within minutes, it was clear he would not have enough fuel to reach safety.

Ejecting over enemy territory meant certain capture or death.

Moment Of Innovation

With Aman’s aircraft rapidly losing fuel and friendly airspace still nearly 100 miles away, Pardo faced an impossible choice.

He had no official procedure to follow, pilots were trained to save themselves when a plane was beyond recovery. However, leaving his wingman behind was not an option.

He recalled an unusual maneuver attempted during the Korean War when fighter ace Robbie Risner had pushed a fellow pilot’s stricken jet out of North Korea using his own plane’s nose.

Though later deemed too risky for standard operations, Pardo now saw no other way. He instructed Aman to lower his tailhook, a mechanism designed for aircraft carrier landings, and positioned the nose of his own F-4 beneath it.

The plan was simple but incredibly risky. The tailhook was not designed for such pressure, and maintaining steady contact was nearly impossible. The turbulence from the two jets, combined with the difficulty of keeping perfect alignment, caused the nose of Pardo’s jet to slip repeatedly.

Each time he lost contact, he had to reposition and try again. Eventually, he found a steady force technique that allowed him to push Aman’s jet forward.

Struggling Against Physics and Fire

As Pardo pushed Aman’s aircraft toward Laos, a new problem arose. His own F-4 had taken significant damage from enemy fire, and one of his engines caught fire mid-maneuver.

He shut it down, restarted it, and watched it catch fire again. He repeated this process multiple times, trying to extend the push as long as possible.

Adding to the challenge, turbulence between the two jets created aerodynamic challenges that required Pardo to constantly adjust his position. Even slight misalignments could have caused catastrophic damage to both aircraft.

When the maneuver began, the two aircraft were flying at 30,000 feet, but they were steadily losing altitude. Pardo had to balance speed and power while ensuring Aman’s aircraft didn’t spiral out of control.

For nearly 88 miles, Pardo’s push kept Aman’s jet in the air. When Aman’s fuel finally ran out, they had just reached Laotian airspace.

The crews ejected safely, but their ordeal wasn’t over yet. Aman and Houghton were pursued by North Vietnamese soldiers on the ground but managed to evade capture until U.S. rescue helicopters arrived. Pardo, who bailed out last, was picked up 45 minutes later.

Aftermath & Recognition

Despite the extraordinary nature of Pardo’s actions, his heroism was not immediately recognized.

In fact, he initially faced scrutiny for losing an expensive aircraft. Some military officials even considered charging him with the loss of his F-4.

In an interview, he said, “Being an Air Force veteran means a lot to me, especially having the honor of serving in combat. It doesn’t give me any extra privileges, but I can guarantee you, it makes me feel better about who I am.”

It was not until 1989, more than two decades later, that Pardo and his backseat officer, Steve Wayne, were awarded the Silver Star for their actions that day. Aviation artist Steve Ferguson later immortalized the event in a striking painting.

Despite acts of courage like Pardo’s, the Vietnam War ultimately ended in failure for the United States. North Vietnamese forces, backed by Soviet and Chinese support, waged a relentless guerrilla war, gradually wearing down U.S. and South Vietnamese troops.

The war cost America more than 58,000 lives and billions of dollars, sparking widespread anti-war protests at home.

Political pressure forced the U.S. to gradually withdraw, and by 1973, most American forces had left Vietnam. In 1975, North Vietnamese troops captured Saigon, bringing the war to a definitive end and unifying the country under communist rule.

Pardo’s heroism extended beyond the battlefield. Years later, when he learned that Earl Aman had been diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and had lost his voice and mobility, he stepped up again.

He founded the Earl Aman Foundation, raising funds to provide his former wingman with a voice synthesizer, motorized wheelchair, and computer. The foundation later expanded to assist other veterans in need.

“If one of us gets in trouble,” Pardo famously said, “everyone else gets together to help.”

Bob Pardo passed away on December 5, 2023, at the age of 89, in College Station, Texas. His legacy as a fearless pilot and loyal comrade remains an enduring part of military aviation history.

Bob Pardo’s reflections on his mission are often summarized by his iconic statement:

“You don’t leave a wingman.”

- Penned By: Mohd. Asif Khan, ET Desk

- Mail us at: editor (at) eurasiantimes.com