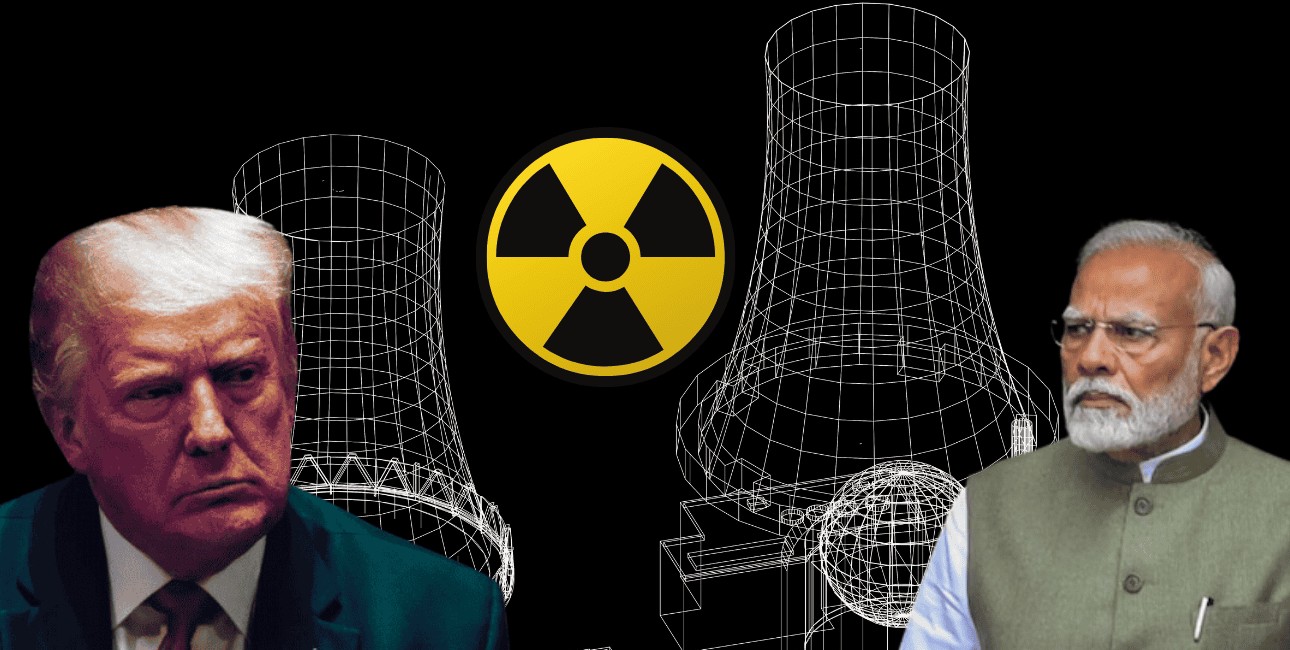

In his just concluded farewell visit to India, the outgoing U.S. National Security Advisor (NSA) Jake Sullivan announced that the potential of the stalled nuclear deal between the two countries would now be realized with Washington removing Indian entities, including the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, from its restricted list to boost nuclear power and high-tech cooperation.

These restrictions were imposed following India’s nuclear weapons tests in 1998. Originally numbering over 200, many such Indian entities, though, have been removed from this list as Indo-U.S. bilateral relations improved over time.

But what about India? After all, more than the U.S., Indian laws have proved to be the real bottlenecks for American companies in setting up or collaborating with Indian nuclear power plants (NPP).

It may be noted that on July 18, 2005, India and the U.S. announced the launch of the Civil Nuclear Cooperation Initiative. Under the parameters of this initiative, India was to commit all of its civilian nuclear facilities to IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) safeguards.

On August 1, 2008, the IAEA Board of Governors approved India’s safeguards agreement, paving the way for exemption from restrictions on countries for trade and partnership with India’s expanding peaceful nuclear sector.

The idea was that American and Indian companies would partner together to foster growth in India’s civil nuclear sector, create a clean energy source that would benefit the environment, and offer India greater energy security with stable energy sources for its large and growing economy.

In fact, it is ironic that though the landmark India-US civil nuclear agreement was the result of the shared vision of the then U.S. President George Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to end India’s international isolation in the field of peaceful use of nuclear energy, it is Russia, not America, that has reaped its real dividends.

Following the summit meeting between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and US President Barack Obama in 2016, it was officially stated that “Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd (NPCIL) and US firm Westinghouse have agreed to begin engineering and site design work immediately for six nuclear power plant reactors in India and conclude contractual arrangements by June 2017.”

Apparently, the proposed reactors worth billions of dollars, which were supposed to be stationed in Gujarat earlier, were later shifted to Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat could not overcome the land acquisition hurdles. The NPCIL is believed to have made a down payment for acquiring 2,000 acres (800 hectares) in Srikakulam district for this purpose. But things have not moved beyond.

There has been a big bottleneck, and that is India’s unique nuclear liability laws of 2010 that talk of compensation in the event of nuclear accidents in a plant. The universal practice is that in the event of an accident, the NPP (Nuclear Power Plant) gives compensation.

No nuclear-exporting country or firm undertakes the responsibility of safety, operations, and maintenance of the NPP to which it has sold fuel and technology. There has to be a national law or bilateral arrangements or international liability regimes — such as the Vienna-based Convention on Supplementary Compensation (CSC) for Nuclear Damage or Paris Convention on Third Party Nuclear Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy — for the exporter and importer to manage liability in case any nuclear accident takes place affecting a third party or the country.

Based on this principle, India passed the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (CLNDA) in 2010 in Parliament that places responsibility for any nuclear accident with the operator, as is the standard internationally, and limits total liability to around US$450 million “or such higher amount that the Central Government may specify by notification.”

Operator liability is capped at Rs 1,500 crore (US$285 million) or such higher amount that the Central government may notify, beyond which the Central government is liable, though the government liability amount is limited to the rupee equivalent of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs).

It may be noted that CLNDA was framed and debated in the context of strong national awareness of the Bhopal disaster in 1984, probably the world’s worst industrial accident. (A Union Carbide (51% US-owned) chemical plant in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh released a deadly mix of methyl isocyanate and other gases due to operator error and poor plant design, killing some 15,000 people and badly affecting some 100,000 others. The company paid out some US$ 1 billion in compensation – widely considered inadequate).

However, comparing the situation of an NPP with the Bhopal gas tragedy is irrelevant since Union Carbide, owner of the Bhopal plant, was a foreign body (American organization). In contrast, here, the government of India owns the NPP. And the government can always go beyond the written liability amount by either meeting the excess amount from its own exchequer or from international sources such as the CSC.

Coming back to CLNDA, even after compensation has been paid by the operator (or its insurers), clause 17(b) allows the operator to have legal recourse to the supplier for up to 80 years after the plant starts up if, in the opinion of an Indian court the “nuclear incident has resulted as a consequence of an act of supplier or his employee, which includes supply of equipment or material with patent or latent defects or sub-standard services.”

This clause giving recourse to the supplier for an operational plant is said to be contrary to international conventions and undermines the channeling principle fundamental to nuclear liability internationally. Besides, no limit has been set on suppliers’ liability. The supplier community has interpreted this provision to be ambiguous, rendering it vulnerable to open-ended liability claims.

Incidentally, the CSC, which India signed in 2010 and ratified in 2016, provides for “only” two conditions under which the national law of a country may provide the operator with the “right of recourse,” where they can extract liability from the supplier – if it is expressly agreed upon in the contract or if the nuclear incident “results from an act or omission done with intent to cause damage.”

A second sticking point has been Section 46 of CLNDA, which states that the provisions of the Act ‘were in addition to, and not in derogation of, any other law for the time being in force,’ leading to concerns among the suppliers that they could be subjected to multiple and concurrent liability claims.

The Act, after all, does not prevent a person from bringing proceedings against the operator under any law other than this Act. That could even allow criminal liability to be pursued against the operator and the supplier, it is feared.

Obviously, all potential nuclear suppliers to India have been unhappy, even though the Government of India has said that with India ratifying the CSC, there should not be any misapprehensions.

The Modi government has also taken steps towards creating a nuclear insurance pool to meet any liability cost, which is anyway desirable as, unlike in other countries, all nuclear entities are state-owned. So, there is no private motive to limit liability in cases of a nuclear accident, which, in any case, is the rarest possibility.

Russia, it seems, is considerably comfortable with the insurance factor. It is the only country that has expanded its nuclear cooperation in India by installing additional reactors in Tamil Nadu (Kunndakulam) after the enactment of CLNDA.

There was a breakthrough in negotiations for four more Russian reactors meant for the Kudankulam plant (each of which is valued at US$2.5 billion), following India’s public sector General Insurance Company’s evaluation of each component of the Russian reactors and prescription of a 20-year insurance premium that would be charged to cover Russia’s liability for an accident.

However, American company Westinghouse, which is to set up units in Andhra Pradesh, is yet to follow the Russian example. It still seems to have issues with India’s nuclear-liability regime‘s foreign technology provision.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board of the EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, and strategic affairs for nearly three decades. He is a former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and a recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com