China, which is home to 40 major transboundary rivers, ranks fourth in global freshwater reserves. Still, it faces severe water scarcity and has the second-lowest per capita water supply of any country in the world, according to some studies.

Being the upper riparian state, China has a distinct advantage in utilizing these water resources. However, Beijing has remained vague and ambivalent in showing its dedication to international water norms, and its decisions regarding these rivers have often caused worries regarding water security for lower riparian states such as India.

It is widely known how the communist country, for decades, has been embroiled in disputes with many Asian nations over the construction of dams upstream. Now, it has emerged that China is charging India millions of dollars for hydrological information on transboundary rivers. It appears that the country is now using water diplomacy to supplement its military endeavors in the region.

China’s Water scarcity

“China’s water scarcity problem is quite intense. The water stress level in China is increasing and their agriculture, industry, and transportation all have a high water requirement,” Srikanth Kondapalli, professor of China Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, told The EurAsian Times.

The country has 20% of the world’s population but only 7% of its freshwater. Vast regions, especially those in the northern part of China, suffer from water scarcity worse than that in the dry Middle East.

Not only have thousands of rivers within China disappeared, industrialization and pollution have also rendered much of the remaining water unfit for use. Some estimates state that 80 percent to 90 percent of the country’s groundwater, along with half of its riverine water is too dirty to drink.

In fact, the water contamination levels are so high in the country that over half of China’s groundwater, and one-fourth of its river water is not even suitable for use in industry or farming. In addition, there is the fact that a lot of China’s freshwater is concentrated in areas such as Tibet.

Increasing water problems are causing geopolitical tensions as China tries to exercise control over these vital natural resources.

Exploiting The Mekong

The Mekong is a 4,350-kilometer-long river that originates in China as the Lancang River and flows through Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar, before draining into the South China Sea through Vietnam.

The river is the lifeline of several Southeast Asian nations, supporting the livelihood of around 200 million people.

China built its first dam on the upper Mekong in the 1990s. It is currently running 11 dams along the river. Beijing also has plans to build more dams for the purpose of generating hydropower. However, some of the giant dams have triggered recurring droughts and devastating floods in countries including Thailand and Laos that are dependent on the Mekong.

A US-government-funded study that came out in April 2020 and was conducted by research and consulting firm Eyes on Eart has found that some of these dams have changed the natural water flow of the river, resulting in the Lower Mekong recording “some of its lowest river levels ever throughout most of the year”.

China has bigger plans for this river, though. Its master plan could include opening a passage for massive cargo from the Yunnan province all the way to the South China Sea. This transportation may potentially include military ships in the future.

Myitsone Dam Fiasco

China had provided $3.6 billion for the construction of the Myitsone dam at the source of the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar. This was slated to be the largest of seven dams that China’s State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) had promised to build in the region. Some estimates said that this single project would generate more energy than what the entire country was producing then.

While the full contract that the then military government signed with SPIC is not available for public scrutiny, the former deputy minister of Myanmar’s state power company, U Maw Thar Htwe, in an interview with BBC Burmese had revealed that 90% of the electricity generated by the dam would go back to China.

Not only this, but the dam would also displace thousands of people and would flood an area the size of Singapore if built. The construction of the massive project was halted in 2011 due to widespread protests against it. China has been lobbying for the work to resume.

Issues In South Asia

The Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra/Jamuna River supports the lives of more than 130 million people in China, India, and Bangladesh. However, the river that originates from western Tibet is also the subject of major disputes.

The three riparian states do not have a water-sharing agreement amongst themselves and dam construction by upper riparian state — China — is viewed as a threat by downstream countries — India and Bangladesh, respectively.

The Chinese government’s outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan, issued in November 2020, articulates the country’s national development goals between 2021 and 2025. The document stated an ambition to “implement …the downstream hydropower development of the Yarlung Zangbo River.”

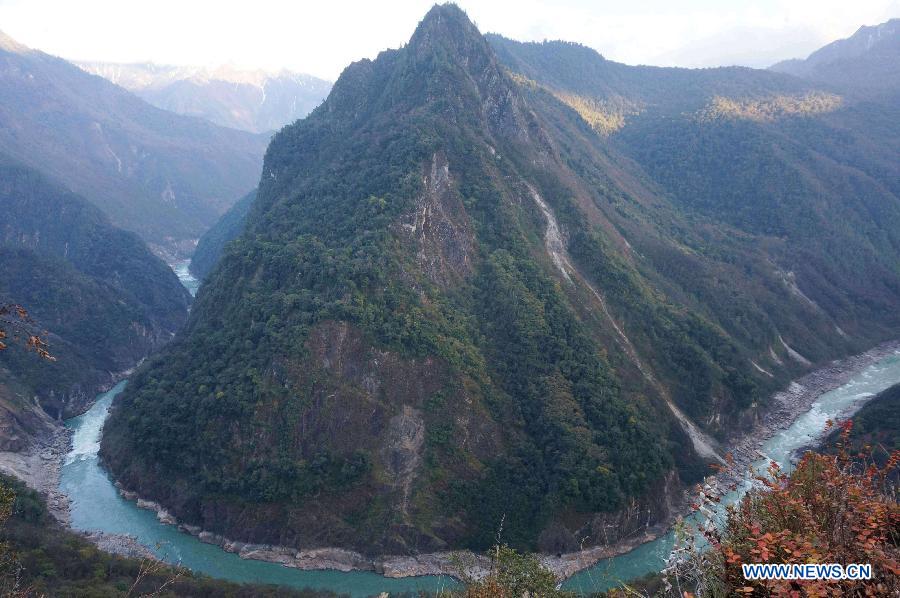

The language in this outline is significant because it highlights the aim of moving the center of Chinese hydropower construction closer to Indian territory. The “great bend” section of the river that lies closest to India features a two-kilometer drop spread over 50 kilometers. This is ideal for electricity generation.

The Brahmaputra river accounts for close to 30 percent of India’s freshwater resources and about 44 percent of its total hydropower potential.

Given its significance to the country’s water and energy security, and the link to ongoing territorial disputes (the waterway passes through the contested Arunachal region), India is wary of China’s designs for the river. New Delhi has expressed concern regarding China’s intention to divert waters from the river to its drought-prone northwestern region ever since the idea was floated in 1986.

Prof. Kondapalli noted that India has close to 140-150 billion cubic meters of the river’s water passing through the Indian territory. “China has already completed covering 31 billion cubic meters as part of its North and Central projects. India will have a problem if there is a diversion of 62 billion cubic meters. The Government of India let the Chinese build 36 dams on the river as they were assured that these will be run-of-the-river projects, not diversion ones. Either way, through the other tributaries, India would still have enough water and the suggestion for these dams didn’t really pinch the country at that time,” he added.

India Paying Millions Of Rupees To China

India and China have signed Memorandums of Understanding for sharing hydrological data on the Langqen Zangbod/Sutlej and the Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra rivers. Under the agreements, China provides data from the three hydrological stations at Nugesha, Yangcun, and Nuxia on the Yarlung Zangbo river from May 15 to October 15, and from Tsada on the Langqen Zangbod from June 1 to October 15 every year. The information provided is significant for India for preparing for flood control and disaster management.

For the data it shared between 2002 and 2007, China did not charge India anything. However, there seems to be a new norm in place.

In 2019, professor Nimmi Kurian of the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research (CPR) revealed that in the absence of an institutional mechanism, India had to pay close to Rs 8.2 million to China every year for accessing water information from the Brahmaputra every year.

“The argument that is made for the payment is on the ground that these three stations are in remote locations and China has difficulty in accessing and the cost involved in fetching the hydrological data. So, the lower riparian should also share the burden of accessing the data,” Kurian said.

Recently, The Quint published a report citing Central Government data revealing that India paid close to Rs 158 million so far to China for hydrological information on the Sutlej and Brahmputra rivers that originate in Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR).

“In terms of the money, the MOU suggests that India pay for the reading for the monsoon. That is the payment India has to make because people have to go to the specific area and measure the water. There is a technical cost involved, we do not know exactly how much,” Kondapalli said.

China also seems to be controlling the flow of information in alignment with military confrontations. During the 73-day Doklam stand-off between India and China in 2017 Beijing had stopped sharing the data, saying that the hydrological gathering sites were washed away due to floods. It resumed the practice from 2018 onward.

Kondapalli said, “China used the transboundary rivers that it has with India as a means of taking revenge over certain actions that did not sit well with China. It did so in Galwan, and in Doklam. We didn’t have measurements of waters during Doklam. What that means is that they are absolutely using these rivers in that particular fashion. Based on these precedents, and the background in Doklam and Galwan, one could reasonably speculate that there is a chance that China is likely to punish India in this way in the future as well. This is the coercive diplomacy on water.”

He noted that China has at least one experience with using water as a weapon, recounting that “Chiang Kai-Shek, in 1938, during the second Sino-Japanese war, busted a dam on the Yellow River and drowned the Japanese troops situated in the lower region. So, if India crosses the line, China can also take an extreme step and burst the Motuo dam or one of the other dams that they are constructing. This is an extreme step with minimal precedence, though.”

Not All Bad

In their book, China’s International Transboundary Rivers, writers Lei Xie and Shaofeng Jia highlight that the country has engaged in a number of diplomatic initiatives with the Mekong countries to allow trust-building with these lower riparian nations. This includes consultation, information sharing, disaster control, and biodiversity protection.

In Kazakhstan, disagreement over shared transboundary rivers is a liability between the two states. Here, China is seeking to utilize water resources for the development of its western Xinjiang region. However, since Kazakhstan is a lower riparian country, its water security is potentially at risk due to China’s water exploitation practices. To sort this issue, the two countries have engaged in various trust-building diplomatic initiatives.

Lastly, the Amur, a transboundary river shared between Russia, Mongolia, and China comes up as a success story. Here, water diplomacy between Moscow and Beijing is characterized by stability, reflected in the large number of bilateral agreements signed by both parties.

- Contact the author at: shreyya.mundhra@gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News