Is China India’s fiercest military rival or closest business associate? Or both? The standard theory of international relations suggests that trade brings peace. Two nations, which trade together, render themselves reciprocally dependent; for if one has an interest in buying, the other has an interest in selling. Therefore, the incentive to use military force in inter-state relations is limited.

The converse is also equally true, it is suggested. Fighting nations do not trade among or between themselves. But this theory seems to be partly true. It may have worked elsewhere, but it is not able to explain the state of India-China relations, as evolved over the last decade or so.

Militarily or politically there have been many standoffs during this period, including the continuing one over Ladakh, between India and China. But that has not impacted their bilateral trade. In fact, as will be elaborated later, each Indian friendly gesture during this period has been followed by Chinese hostility but that hostility has had no adverse impact on the bilateral trade.

Following the Chinese violation of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the disputed Sino-border areas in Ladakh, India had imposed many restrictions on the Chinese goods and investments, but that has not affected the overall bilateral trade figure, which has grown 44 percent in 2021. It is now revealed that Indian imports grew over a record 46 percent while exports were up 35 percent.

Over $100B Bilateral Trade

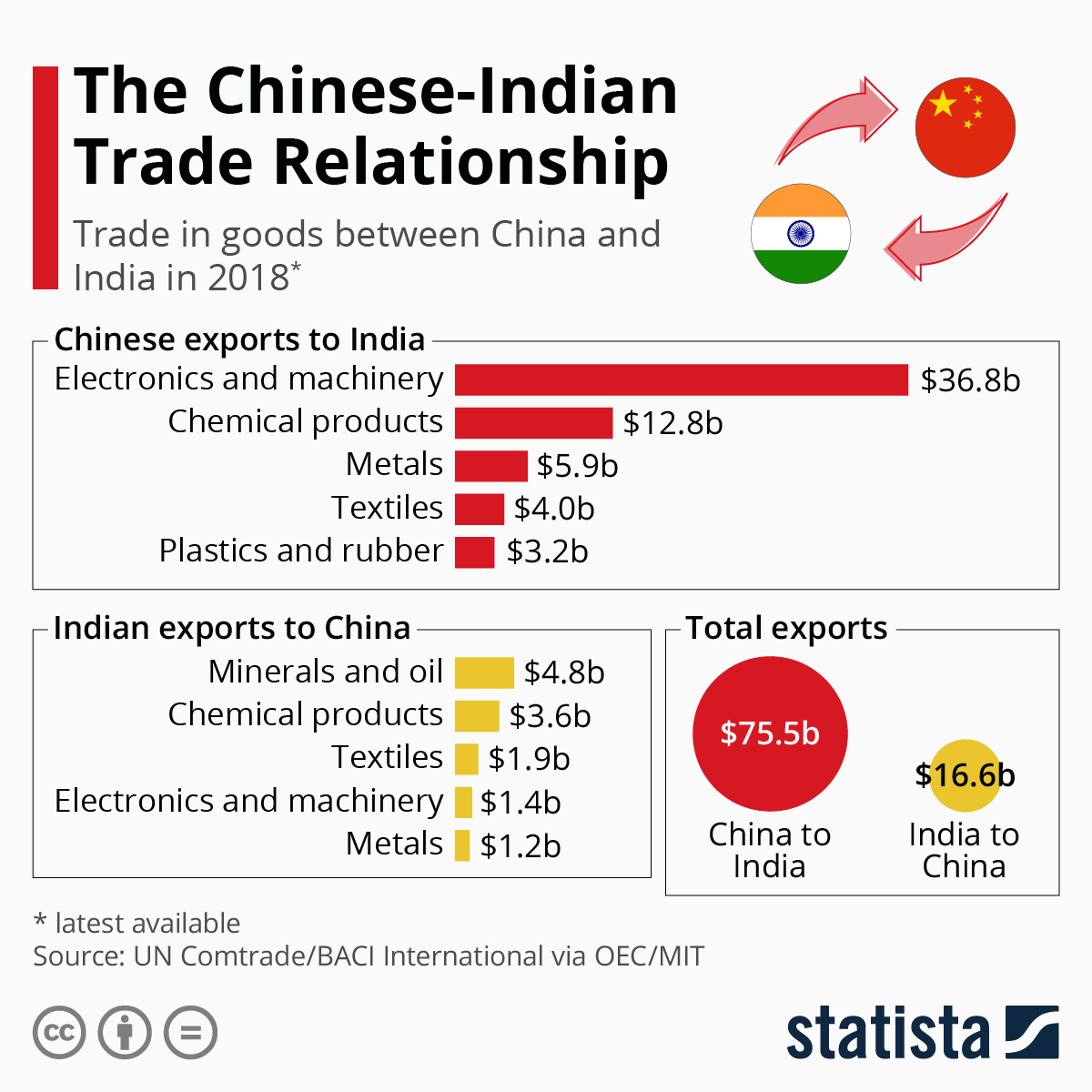

India’s total trade with China was $125.7 billion in 2021 although it was predominantly in favor of China. In fact, this was the first time that bilateral trade crossed the $100 billion mark. Another noteworthy fact is that increased imports pushed India’s trade deficit with China to $69.4 billion in 2021, up from $45.9 billion in 2020 and $56.8 billion in 2019.

In the April-November period last year, China was India’s second-largest trading partner, after the US. Some of India’s key imports from China include smartphones, components for smartphones and automobiles, telecom equipment, plastic and metallic goods, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), whereas Indian exports to China include essentially raw material, particularly iron ore.

No wonder why, in an excellent study, Delhi University scholars Bipin K. Tiwary and Anubhav Roy, have found out that “the political-military and economic strands of India-China relations have seen a divergence in the past decade, with bilateral business and economic interactions quietly continuing – or even improving – despite political-military strains over multiple discords continuing”.

So much so that within six months of the Ladakh standoff in 2020 (April to December), during which the Indian government had devised many measures to scale down business attachments to China and commissioned plants to accelerate the indigenous production of items that were major Chinese exports to the country, China reclaimed its spot as India’s top trading partner. Till then, i.e. from FY 2017- 18, the US was India’s largest trading partner (it has reclaimed this position though last year).

In FY 2013-14, China had replaced the UAE as India’s top overall trading partner. It had retained this position for four years until the US displaced it in FY 2017-18.

China Provoked India Despite Modi-Xi ‘Bonhomie’

Incidentally, these are broadly the years when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President XI Jinping had met as many as 18 times (one-on-one meetings and those on the sidelines of multinational summits), the most by any Indian head of the government.

But these were also the years (broadly 2014-20) when China did its best to provoke India, militarily and politically, Tiwary and Roy have aptly pointed out.

First, in September 2014, the Chinese PLA made an unprovoked intrusion in Ladakh’s Chumar sector.

Second, In October 2016, China persisted with blocking India’s bid to get Pakistani terrorist outfit Jaish-e-Mohammad chief Masood Azhar blacklisted by the Sanctions Committee of the UN Security Council.

Third, in November 2016, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), traversing through India’s territory in Pak-occupied Kashmir (POK) became partially functional despite repeated protests by Delhi.

Fourth, between June and August 2017, the Indian Army and the PLA remained locked in a standoff at the Doklam plateau near the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction.

Fifth, in June 2019, going against the overwhelming majority, China, under a specious plea of ‘consensus’, blocked a discussion at the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group on Indian admission to the body.

Sitting 200kms north of #India #Bhutan #Doklam is the #PLAAF #Xigaze dual use airbase, recent sat images of monolith in #Tibet show how #China has silently expanded its structure and continues to use its network of UAV's,Jets and Radar sites to monitor #india uncontested pic.twitter.com/HRgamJ5mnT

— Damien Symon (@detresfa_) September 5, 2019

Sixth, in June 2020, it crossed the LAC in Ladakh that ensued the egregious skirmish at Galwan which resulted in the death of reportedly 20 Indian and at least 38 Chinese soldiers.

Cars, Smartphones, Startup Funds

However, during all these years, and this has been highlighted prominently by Tiwary and Roy, China’s business and financial interests in India expanded phenomenally. As many as 92 Indian startups came up with Chinese investments. Xiaomi of China emerged as India’s largest selling mobile. MG, Volvo, and Great Wall Motors were allowed to cast their footprints in India’s car market.

Incidentally, the Modi government constructed the world’s tallest statue, that of late Home Minister Sardar Patel, in Gujarat by “using 553 bronze panels” made in China.

Another trend that has been noticed is that many Indian startups and established companies, particularly those dealing with the automobile sector, have had direct or indirect links with Chinese investments or collaborations.

As it is, the Chinese electric car flagship ZS EV has been in India since 2019. It has partnered with “eChargeBays”, a Delhi-based start-up in establishing public EV chargers. It has also partnered with Tata Power in this regard.

Reportedly, China is now the single largest source of automobile parts imported by India. The latest available data suggests that the Chinese share in this segment is as high as 27 percent, with an annual worth of $4.7 billion. And this segment includes critical car parts like engine pistons, transmission drives, steering and body components. Car manufacturers like even Maruti Suzuki India Limited have admitted that India currently “cannot make the Chinese-exported parts or source them from elsewhere cheaply”.

Of course, it is a global phenomenon, and India cannot escape from the hard reality, that China’s fast globalizing supply chains and aggressive overseas corporate acquisitions, which, in turn, enter foreign territories, for instance, as British or American companies (though in reality, these are now owned by China), have made Beijing’s footprints omnipresent all over the world.

As long as this Chinese supply chain is not broken, one should not be surprised to see instances of contrast between the political-military and economic strands of the countries in their relationship with China. This is true of whether it is the United States, Japan or India, or any other.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of Editorial Board – EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy on strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies. CONTACT: prakash.nanda@hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News