China is all set to weaponize water against India by building the world’s largest hydropower project—the 60,000 MW Motuo mega-dam—on the Yarlung Tsangpo River, which is known in India as the mighty Brahmaputra River.

In the post-Galwan world, New Delhi is worried that the dam will give Beijing the power to control the river flow, which provides drinking water to an estimated 1.8 billion people in countries including China, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh.

The mega dam is in addition to the series of dams that China has built to tame Tsangpo. China’s ‘Mother of all Dams’ can curtail the river flow during the lean season and trigger artificial floods during the rainy season. A concerned India has proposed an 11,000 MW hydropower project on the Siang River in Arunachal’s Upper Siang district.

The dam design includes a “buffer storage” of over 9 billion cubic meters of water during peak monsoons. This would act as a reserve when water flow is reduced or act as a buffer for downstream areas of Arunachal and Assam if China releases sudden water.

Outdated Tech, Delayed Delivery, Russian S-400 AD System No ‘Game Changer’ For Indian Military: OPED

The proposed dam aims to strengthen India’s water-sharing rights as a riparian state.

India’s fears are not unfounded. In 2021, China cut the water flow of the Mekong River by 50 percent for three weeks without a prior warning. The flow was cut ostensibly for power-line maintenance, but this affected the millions of people living along the waterways in the Southeast Asian countries of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam.

In 2019, China’s dams in the upper Mekong River basin retained a record amount of water, setting a new record despite experiencing above-average rainfall in the region during the wet season. Consequently, countries downstream faced an unprecedented drought during this typically wet season.

Since 2019, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam have experienced the most severe and prolonged drought on record. The region’s economy and food security have been adversely impacted. Farmers have lost crops, fish populations have dwindled, and reservoir levels have dangerously decreased.

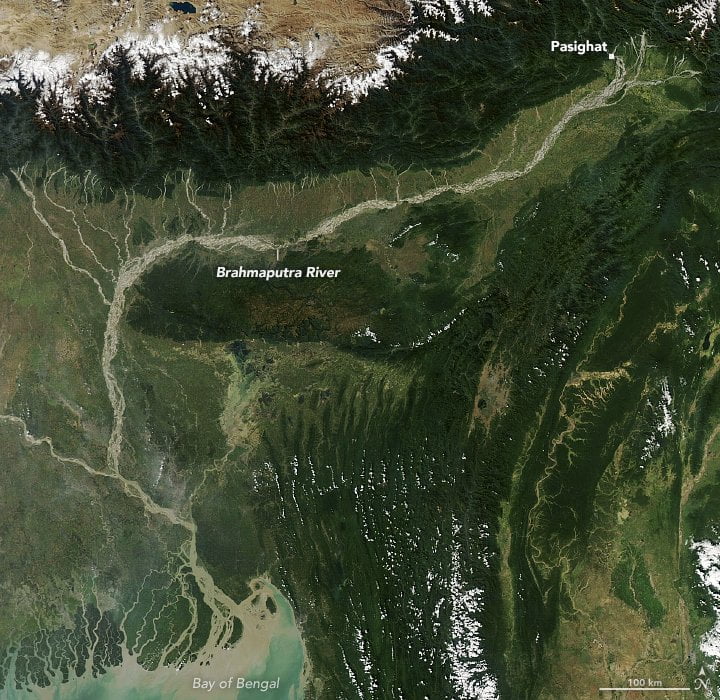

Now, the Yarlung Tsangpo is one of the world’s largest transnational river systems. It originates in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau in southwest China, flows 2,900 kilometers across southern Tibet via the Himalayas, and enters India, where it is called the Brahmaputra, through the Indian states of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh (which China claims as South Tibet).

Outdated Tech, Delayed Delivery, Russian S-400 AD System No ‘Game Changer’ For Indian Military: OPED

Siang is a tributary of Brahmaputra. In 2017, the water of Siang turned black and became unsuitable for drinking, damaging the ecology and disrupting local agricultural production. Indian officials publicly blamed China. Nonetheless, China dismissed the accusations as highly exaggerated.

Experts believe that constructing dams on rivers such as the Brahmaputra will allow China to control the flow of water downstream.

“This enables China to use water as a geopolitical tool, potentially manipulating water levels for irrigation, power generation, or flood control, which has impacted India and Bangladesh,” Neeraj Singh Manhas, Special Advisor for South Parley Policy Initiative, Republic of Korea told the EurAsian Times.

He opined: “For China, controlling the headwaters of major rivers provides an upper hand in negotiating with downstream nations. India’s geographic location, with much of its water originating from rivers flowing from China, places it at a disadvantage. India, as a lower riparian state, is dependent on these upstream flows for its agriculture and water security, which makes it vulnerable to any upstream activities by China.”

Manhas sees India’s recent proposal to build its dam on the Siang as a shift in strategy “aiming to assert its water rights and reduce dependence on China’s actions.” The National Hydroelectric Power Corporation will build the Upper Siang hydropower project.

India-China Stand-Off Enters 5th Consecutive Winter; Indian Army Takes ‘Civilian Help’ To Hold Fort!

The dam was first proposed in 2017 by the central government think tank Niti Ayog. It said it would be the country’s biggest hydropower project, with a capacity of 10,000 megawatts.

The NHPC has selected three sites along the Siang River, Uggeng, Ditte Dimme, and Parong, to assess whether the dam is feasible in this area.

The pre-feasibility report assesses the probable cost of the dam and whether it can be constructed in that area. The survey also involves drilling a 200-meter-deep hole to test the strength of the rock surface. The dam is facing considerable opposition from the local population.

Asian NATO: Why India Does Not Back Japan’s Idea Despite Tensions With China & Alliance With Tokyo?

Water Wars In The Himalayas

The Yarlung Tsangpo runs almost 3,000 kilometers through the Tibetan Autonomous Region to the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam and then out into the Bay of Bengal via Bangladesh. It is the highest major river on Earth, running at an average elevation of 4,000 meters.

In the last few years, China has been taming the river to generate hydro-power. But the super dam proposed at the remote stretch of the river known as the Great Bend is the biggest of them all.

The dam site is at the eastern reaches of the Himalayas near the disputed border with the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. It is at a place where the river makes a dramatic U-turn. Here, the river elevation drops fiercely over 2,700 meters within a 50 km stretch before it changes course towards India.

China claims that the project is being constructed to increase life quality in Tibet and manage water scarcity while meeting China’s goal of reaching a carbon emission peak before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

But the dam construction is also driven by geo-political considerations. In 2016, China obstructed the flow of the Xiabuqu River, a Brahmaputra tributary located in Tibet near the Sino-Indian border. On the face of it, the obstruction was done to facilitate the operation of the Lalho hydropower project.

However, it coincided with the time when India was contemplating a review of the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan following the Uri attack. In a research paper, Manhas and Dr. Rahul M. Lad contend that “this trend signifies the potential “weaponization” of transboundary water resources, posing a significant threat to regional stability in South Asia.”

Bangladesh, where millions of people reside in the Brahmaputra basin, will also be adversely affected by the change in the river’s course.

After the Doklam standoff with India, China “abruptly” ceased to share hydrological data for the Brahmaputra River despite previous agreements. In contrast, Bangladesh continued to receive uninterrupted data from China. This behavior by China reflects its intent to utilize water resources as a political tool against India within the South Asian context.