In the covert annals of Cold War espionage, few operations rival the audacity and technical ingenuity of Project AZORIAN. Veiled in secrecy for years, this clandestine mission orchestrated by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) serves as proof of the USA’s resourcefulness and resolve during the geopolitical conflicts of the time.

It all began on February 24, 1968, when the K-129, a Soviet Project 629A ballistic missile submarine, slipped silently from the Rybachiy Naval Base in Kamchatka. Its mission: a routine missile patrol in the Pacific waters northeast of Hawaii.

Operating under strict radio silence for the first two weeks, the submarine failed to report in as scheduled by March 8. Alarm bells rang in the Soviet ranks, triggering a frantic search operation spanning over two months.

A fleet of 36 vessels, complemented by 53 aircraft, scanned more than a million square miles of ocean, battling treacherous waves reaching heights of 45 feet. Despite their efforts, the K-129 remained elusive, lost to the depths.

Unknown to the Soviets, their every move was being closely monitored by the US Navy. Utilizing the sophisticated Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), designed to detect Soviet submarines, the Americans picked up the telltale sound of an exploding vessel within the search area. Armed with this crucial intelligence, they narrowed the search radius to a mere five miles.

Following that, the USA dispatched the USS Halibut, a submarine repurposed for intelligence operations, to locate the K-129. After an exhaustive search lasting more than a month, the Halibut achieved a remarkable breakthrough.

In the depths of the Pacific, some 1,500 miles northwest of Hawaii, the submarine discovered the K-129 resting at an astonishing depth of 16,500 feet.

Despite its tragic fate due to a catastrophic mechanical failure, the K-129 held a treasure trove of strategic importance.

The Russian submarine’s critical components, including its missile silos, remained remarkably intact, potentially harboring at least one, and possibly even two, live R-21 missiles.

Project Azorian

Recognizing the immense value of this find, particularly in the context of the Cold War standoff, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) swiftly assumed control of the covert recovery operation codenamed Project Azorian.

Under the guise of a deep-sea mining venture, the CIA orchestrated a complex salvage mission to retrieve the K-129 and its potentially invaluable cargo of nuclear missiles.

Initially, concepts like utilizing rockets or underwater balloons were examined to raise the wreck, but it soon became evident that the sole viable method would involve a claw affixed to a ship.

At that time, retrieving anything from the staggering depths of 16,500 feet remained an unparalleled feat, especially considering the weight of the object, estimated at around 2,000 tons.

While the deep-sea mining industry was still in its infancy, there was one standout among American companies: Global Marine, renowned for its expertise in crafting ocean mining vessels.

Recognizing the magnitude of the task at hand, the CIA sought the specialized services of Global Marine to construct and operate a vessel of sufficient scale for this unprecedented mission. Additionally, Lockheed was commissioned to design the pivotal component: the claw, aptly named the capture vehicle.

Yet, orchestrating such a clandestine operation required more than just technical prowess; it demanded a carefully crafted cover story. Enter Howard Hughes, the enigmatic Texas oil magnate known for his eccentricities.

His reputation as a recluse provided the perfect smokescreen — a narrative portraying a daring but financially precarious venture to extract manganese nodules using experimental deep-sea mining methods, lending an air of legitimacy to the covert operation.

With Hughes on board, both literally and figuratively, the CIA found a willing collaborator with a history of involvement in government projects.

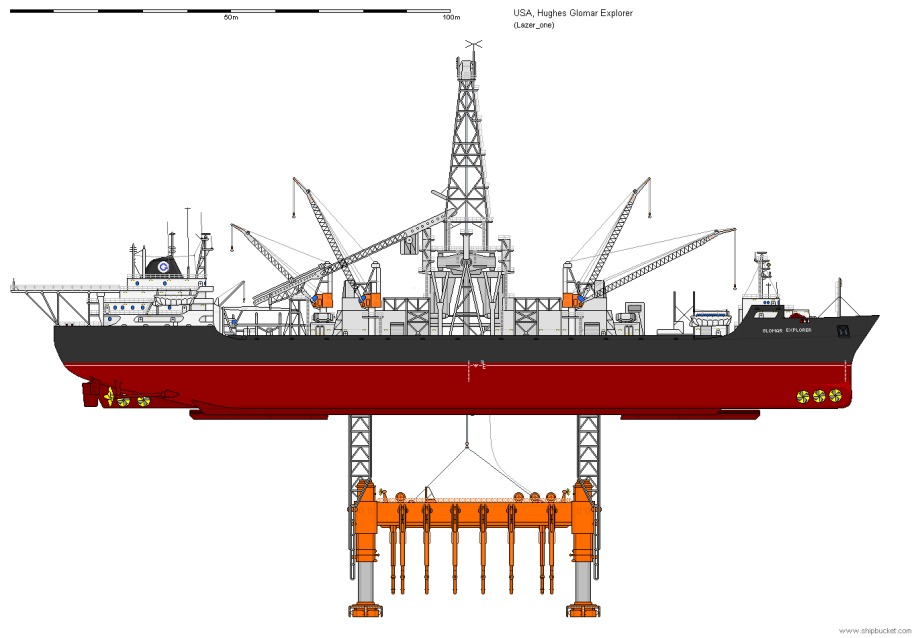

The vessel, built and owned by billionaire Howard Hughes, for this critical mission was the Hughes Glomar Explorer, an imposing 620-foot ship meticulously crafted for the singular purpose of raising K-129 from the sea floor.

Over the following four years, the vessel underwent construction, incorporating various features essential to its task. These included a derrick resembling those found on oil-drilling rigs, a crane for pipe transfer, two towering docking legs, and a substantial claw-like capture apparatus.

Central to its design was a large docking well known as the “moon pool,” capable of containing the raised portion of the submarine, complemented by floor doors for operational convenience.

To safeguard the mission’s confidentiality, the capture vehicle was assembled indoors and then discreetly loaded onto the ship from a submerged barge. With these specialized functionalities, the vessel could execute the entire recovery operation underwater, shielded from the observation of other vessels, aircraft, or surveillance satellites.

The Recovery

On July 4, 1974, six years after the submarine was discovered, the Glomar Explorer finally reached the wreckage site. Over the following month, the crew diligently worked on lowering the capture vehicle into the depths.

During the operation, the Glomar Explorer found itself under surveillance by Soviet vessels on two separate occasions. Initially, a missile-range instrumentation ship monitored the Explorer, conducting helicopter flyovers before departing after a few days.

Subsequently, an ocean-going tug utilized for intelligence gathering lingered in the vicinity for weeks. This tug positioned itself strategically to retrieve debris from the Explorer and engaged in provocative maneuvers, including sailing within proximity of the US ship.

Despite these intrusions, the Soviets remained oblivious to the covert activities unfolding beneath the surface.

Following roughly a month of painstaking efforts, several hooks on the capture apparatus unexpectedly broke, causing two-thirds of the submarine, including crucial components like the missile silos and code room, to plunge back into the depths beyond recovery.

Undeterred by this setback, the American crew persisted in raising what remained of the K-129. Fortunately, the Soviet tug departed just as the submarine’s remnants approached a depth of 1,000 feet below the Explorer.

With the retrieved wreckage aboard, the crew of the Glomar Explorer began the painstaking task of dissecting it en route to the United States.

The CIA had been gearing up for a follow-up recovery endeavor dubbed Project Matador. However, on March 18, 1975, journalist Jack Anderson exposed the details of Project Azorian to the public, defying CIA Director William Colby’s requests for secrecy.

Despite the US government’s silence on the matter, neither confirming nor denying the circulating stories, the situation escalated by late June as the Soviets dispatched a ship to monitor and protect the recovery site.

With the exposure of the Glomar’s covert mission, the White House decided to halt any further recovery operations.

Outcome Of The Operation

With the exposure of the CIA’s covert operation, the White House opted to cancel the planned second recovery effort, effectively shutting down Project Matador. Subsequently, the Soviet Navy intensified surveillance of the ocean surrounding the wreck site.

However, the contents of the retrieved wreckage have remained a subject of debate. Investigative journalist Jack Anderson asserted that Navy experts informed him that the sunken submarine held no significant secrets, branding the entire project a waste of taxpayers’ money.

Yet, alternative accounts suggest that the operation yielded valuable findings. While the CIA has never fully disclosed the specifics of what was recovered, it is widely believed that the haul included at least two nuclear-tipped torpedoes, a collection of documents, and the submarine’s bell.

The recovered section provided valuable insights into Soviet submarine design, including manufacturing locations, component replacement frequencies, and hull thickness.

Among the retrieved items were the remains of six Soviet submariners, who were accorded a formal military burial at sea.

In 1992, Director of Central Intelligence Robert Gates presented a film documenting the burial ceremony of Russian soldiers to Russian President Boris Yeltsin in a gesture of goodwill. Additionally, the USA presented the submarine’s bell to the Russians.

In 1976, the USA’s response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by Rolling Stone reporter Harriet Ann Phillippi resulted in the creation of the “Glomar Response,” a legal tactic developed by the CIA.

When compelled to respond, the agency stated it could neither “confirm nor deny” the existence of records related to the program. Subsequently, a court validated this response as legitimate.

What happened To The Hughes Glomar Explorer?

The Glomar Explorer’s covert operations ended, and after some experimental ocean mining ventures supported by a coalition of industry leaders, it was decommissioned for over 25 years.

However, in the late 1990s, a US petroleum company refurbished the vessel for deep-sea oil drilling and exploration.

Renamed the GSF Explorer, the vessel underwent conversion from 1996 to 1998, marking the commencement of a 30-year lease from the US Navy to Global Marine Drilling at an annual cost of US$1 million.

Subsequently, in 2010, Transocean, an American drilling company, acquired the vessel for US$15 million in cash.

Throughout its 18-year drilling tenure, the Glomar Explorer operated in various locations, including the Gulf of Mexico, Nigeria, the Black Sea, Angola, Indonesia, and India. It served multiple oil company clients and made numerous shipyard and port visits along the way.

Affectionately known as “The Mothership” by crew members, it played a vital role in offshore drilling operations. In April 2015, Transocean announced its decision to scrap the ship. The Glomar Explorer arrived at the ship breakers in Zhoushan, China, on June 5, 2015, marking the end of its storied career.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News