Amid India-US bonhomie over QUAD, it’s interesting to watch how China is maintaining its “all-weather” friendship with Pakistan and an “unbreakable” bond with Russia.

Although it is too soon to prove the existence of a Russia-China-Pakistan ‘axis’, the growing strategic convergence between the three is a significant geopolitical development, especially given the possible formation of power blocs given the growing strategic competition between the US and China.

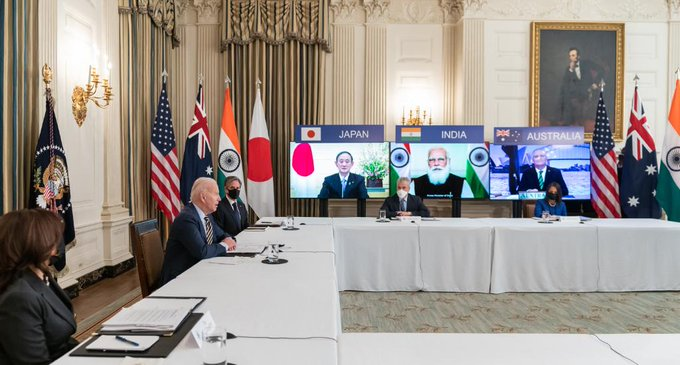

This convergence will most likely play out in the Indo-Pacific—the epicenter of US-China competition. The rechristening of Asia-Pacific as Indo-Pacific is largely a result of growing convergence among the four QUAD countries — India, the United States, Japan, and Australia.

The common vision of the countries for the region—”free, open, inclusive, healthy, anchored by democratic values”— was enshrined in the first-ever joint statement, released after the maiden QUAD summit.

China’s Opposition To QUAD

China has been vocal about its opposition to this “four-side mechanism” as it adheres to the “Cold War mentality.” Both Russia and Pakistan have displayed their ‘pro-China’ tilt on the QUAD, albeit the Russian vision for the region as a whole is more complex.

#Chinese President Xi Jinping and #Russian President Vladimir Putin attended via video link the ground-breaking ceremony of a bilateral nuclear energy cooperation project. pic.twitter.com/Aa4pNULnWN

— Hua Chunying 华春莹 (@SpokespersonCHN) May 19, 2021

Russian foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov’s remarks at the Raisina Dialogue held in New Delhi outlined how despite supporting India’s inclusive Indo-Pacific vision, Moscow is hostile towards QUAD, essentially parroting Chinese concerns about containment.

For Pakistan, America’s growing defense relations and professed commitment to bolster India’s capabilities to counter China, have further strained relations between Islamabad and Washington.

Viewing America’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ as a threat, Pakistan is seeking deeper security cooperation with Russia and China through joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean, exchanging naval officials, and deepening military cooperation.

Pakistan’s PNS Zulfikar frigate is all ready to participate in the Arabian Monsoon exercise with Russian ships in the Arabian Sea after the two navies participated in the Pakistan-hosted biannual maritime multinational naval exercise Aman-2021, which included China and 45 other countries.

Russia-Pakistan-China Convergence

Beyond their shared criticism of QUAD, there are other areas where the strategic objectives of the three countries converge. Despite the Chinese projection of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) as a purely ‘economic’ project, few would deny the strong geopolitical implications it would have—particularly in the Indian Ocean.

Gwadar Port, in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, handed over to the Chinese in 2013 for 40 years provides Beijing direct access to the Indian Ocean through the Arabian Sea. This would extend Chinese power projection well into the Western Indian Ocean, effectively counterbalancing US and Indian naval capabilities.

AT €7.8B, WHY INDIAN RAFALE JETS ARE ‘DOUBLE THE COST’ THAN EGYPTIAN RAFALES?

In 2016, Pakistani media was abuzz with reports of Russia joining the CPEC, which was swiftly denied by the Kremlin, but it has indicated its “strong support” for the project and its intention to link its own Eurasian Economic Union project with CPEC.

According to an article published by a leading Russian think tank, the “only explanation” for Russia deferring participation in CPEC is “respect for India’s sensitivities” given New Delhi’s sovereignty concerns over the nature of the project.

However, in view of the growing ties between Islamabad and Kremlin exemplified in Sergei Lavrov’s visit to Pakistan— the first by a Russian foreign minister in 9 years—has raised apprehensions about whether India can continue to deter Russian participation in the project.

Russia and China’s increasing presence in the resource-rich Western Indian Ocean can be a game-changer in the ongoing geopolitical contest in the region.

Despite being a late entrant, Russia has significantly stepped up its presence in the region, striking a 25-year agreement with Sudan to establish a naval base in the country which will station four Russian ships and up to 300 personnel, although reports suggest Sudan is currently reviewing the deal.

China, which has already penetrated deep into the Indian Ocean through strengthening maritime ties with East African countries, is independently strengthening maritime cooperation with both Russia and Pakistan.

It is against this backdrop that Iran, Russia, and China held their first-ever joint naval exercise in the Northern Indian Ocean in 2019, where Iran reportedly also invited the Pakistani Navy.

Growing Military Ties

Meanwhile, the latest iteration of bilateral naval exercise between China and Pakistan—Sea Guardians 2020—reflects the growing complexity and expanding the scope of their bilateral maritime partnership.

With Pakistan and Russia committing to increasing the frequency of their joint military drills and maritime exercises to fight terrorism and piracy, the possibility of a Russia-China-Pakistan naval exercise, may not be so remote anymore.

Arguably the strongest glue holding the three countries together is a common aversion to the ‘western construct’ of a ‘rules-based order.’

Against the ‘rules-based order’, China and Russia have been parallelly pushing the narrative on ‘global governance’—premised on the centrality of United Nations—as reflected in the Lavrov-Wang joint statement following the Russian foreign minister’s visit to China earlier this year.

Meanwhile, China and Pakistan have strengthened cooperation in multilateral forums such as the United Nations, evident from the recently released joint statement where the two countries pledged to back each other’s “core interests” and “firmly safeguard multilateralism.”

In October last year, Pakistan—on behalf of 55 countries, which included Russia—made a joint statement at the UN “opposing interference in China’s internal affairs under the pretext of Hong Kong.”

In the context of the evolving geo-strategic construct of Indo-Pacific and rapidly fluctuating power relations, each country will act in a manner that maximizes its national interest.

The QUAD countries are working together to defend a regional order which was largely constructed by the United States, from rivals, namely China.

WHY DID NETIZENS ‘MOCK’ NIGERIA FOR JF-17 DEAL WITH PAKISTAN?

China’s careful critique of Western intentions in the Indo-Pacific and representation of QUAD as an “Indo-Pacific NATO” gels well with Russian interests.

The emerging disconnect in US-Pakistan relations has paralleled closer Indo-American ties which have effectively pushed Pakistan closer to China and Russia, binding the three together by shared criticism of what they see as ‘Western hegemony.’

In the current era of strategic uncertainty, the deepening relations between Russia, Pakistan, and China is a major challenge for the QUAD countries, although they are gaining recognition for their agenda from regional and extra-regional actors.

Going forward, one of the first steps QUAD must take is to convince actors, especially Southeast Asian countries, that QUAD is indeed not an ‘Asian NATO.’ To do this, it must begin by robustly defining what it means by a ‘rules-based order’ and clarify that it is not at variance with multilateralism or ASEAN centrality.

Written by Rushali Saha

(The author is a Research Associate at the Centre for Airpower Studies, New Delhi)