The presidential and parliamentary election in Turkey is scheduled for May 14. Political commentators give special importance to this election. They believe it will decide whether Turkey remains glued to drawing political support from Islamic religious positioning or envisions a liberal West-impacted democratic and progressive nation.

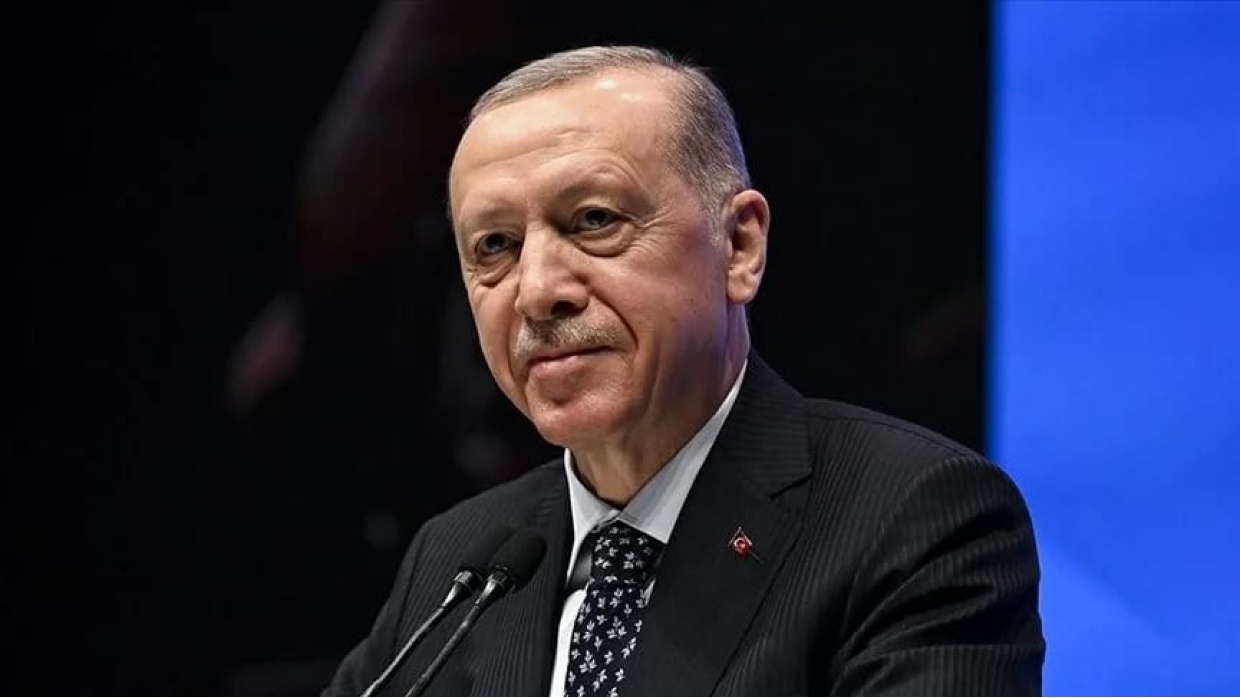

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has remained in power for nearly twenty years. In recent years, he has pandered to a pro-Islamist predisposition, sometimes aggressively and at other times like a benign fanatic.

Erdogan recently converted Hagia Sophia from a museum into a mosque, a decision that apparently involved no consultation and was executed swiftly after a surprise announcement. What were Erdogan’s true motivations for taking this provocative step?

Hagia Sophia (“Holy Wisdom” in Latin) was built in the 4th century as a Byzantine church. It was converted into a mosque following a decision by the Turkish court and the final confirmation of the Turkish President.

Many saw the decision as anti-Christian, but it was intended, first and foremost, to please Arab Muslims. The President wished to establish himself as the worthiest leader to stand at the head of the Sunni Muslim world. He carefully displays his religiosity, regularly quotes verses from the Qur’an in his speeches, and frequently prays in public.

Erdogan has always seen himself as the Muslim ummah/community leader. He seeks to regain the glory of the Ottoman Empire, whose cherished conquests have parallels with present Turkish actions as listed below:

Turkey’s occupation of Northern Cyprus, the arrival of Turkish fighters in Libya; invasions by the Turkish army of Syrian territory and occupation of Kurdish towns; Erdogan’s tacit support for ISIS forces; absorption into Turkey of thousands of Egyptian activists from the Muslim Brotherhood and granting them refugee status in Turkey; efforts to control large areas in Sudan; seeking to weaken Saudi Arabia’s position as custodian of Islam’s holiest shrines in Mecca and Medina; interference in Israel’s internal affairs and its conflict with the Palestinians, and later taking a stance against India in the context of Kashmir.

Erdogan is trying to present himself as a defender of the Palestinians and the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This positioning is part and parcel of his desire to expand Turkey’s activities and ultimately take over the Arab world.

Two years ago, the abortive Malaysian meeting of three anti-Saudi Arabia countries, namely Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan, testified to Erdogan’s aspiration to project himself as the sole leader of the Islamic world.

In recent years, tension among Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, and the Emirates divided the Middle East into fronts. Turkey became a defender of Qatar along with Iran.

This led to a covert war between Ankara and Riyadh that reached new heights in the assassinated journalist Jamal Khashoggi affair. The Turkish army has bases in Qatar and protects the Emir and his land.

Some believe that through such actions, Erdogan is trying to steal the kingdom’s role as defender of the Arabs, Muslims, and their two holiest sites in Saudi territory. His popularity among Arabs is undoubtedly high, especially when he is hostile to Israel. It should be noted that the Turkish army is considered the second-strongest in the Middle East after Israel.

On May 14, Erdogan’s Peoples Alliance will lock horns with the Nation’s Alliance in a presidential and parliamentary election. Opposition parties welded into Nation’s Alliance hope to give a democratic and pro-Western boost to Turkey once called the ‘Sick Man of Europe.’

The country is polarized between Islamists and liberal modernists. If incumbency is accepted as crucially catalytic, then it goes against Erdogan, who has been in power for two decades. Change is paramount in a democratic dispensation.

Whether the election sends Erdogan home or reinstates him in power, in either case, the country is standing at historic crossroads.

Three political groupings are in the fray. Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) leads a broader group of smaller parties, the People’s Alliance, and includes MPH or Nationalist Movement Party. It comprises the main opposition Kemalist Republican People’s Party (CHP) and five smaller parties that need to synthesize their ideologies if they want to dislodge Erdogan. Kemal Kilicdaroglu is its chosen leader.

The manifesto released by the Nation’s Alliance in January proposes stripping the powers of the President and restoring the parliamentary system compromised through a presidential order in 2018.

It aims at bringing in several constitutional amendments to overhaul the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary and add accountability. This appears to be a bold agenda and can sail through only if the Nation’s Alliance remains united in case of winning in elections. Constitutional amendments require large majorities in the Grand National Assembly.

Predicting the outcome of presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey is somewhat tricky. There could be a neck-to-neck fight. Generally speaking, electoral behavior in Turkey is influenced by various factors like religion, geography, and economic performance. In contemporary times and societies with an open mind, the main criterion for judging the performance of a government is the economic area.

For them, it has priority over other factors. During its earlier stint, the Erdogan regime’s efforts to advance the national economy had won public appreciation. However, of late, it had to face many challenges. A Gallop survey in 2022 showed that a record-high 39% of Turkish citizens were “suffering.”

Last year, inflation hit 64%, and the lira lost some 30% of its value against the US dollar. The situation worsened after the February earthquake, and according to the World Bank, the repair costs may exceed $34 billion.

A recent Global Academy survey shows that 28.9% of voters care most about economic problems, followed by terrorism (15.4%), the refugee crisis (9.4%), restriction of personnel freedom and rights (7.8%), foreign policy (6.1%) and Kurdish issue (4.6%).

It may be mentioned that India was the first country to bring relief and medical assistance to the quake-afflicted populace in Tukey, and Erdogan lost no time to speak against India in the United Nations thanklessly.

Commenting on Erdogan’s foreign policy, the Begin-Saadat Center for Strategy writes in its Perspective Paper: “Notwithstanding an apparent trend of Turkey normalizing relations with several countries, notably Israel, Egypt, and UAE, Erdogan’s acrobatics between East and West and his muscular strategy in the Mediterranean have elicited concern in Washington, Jerusalem, and other capitals such as Athens and Cairo.”

Erdogan’s victory would likely lead to a replication of standard policies in the Mediterranean in which partnerships are paired with tensions. A governmental change could bring Turkey closer to the US and the EU.

- KN Pandita (Padma Shri) is the former Director of the Center of Central Asian Studies at Kashmir University. Views expressed here are of the author’s.

- Mail EurAsian Times at etdesk(at)eurasiantimes.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News