In the years following 9/11, the global manhunt for Osama bin Laden became the symbol of America’s relentless pursuit of justice. Yet, for three decades, another name —Warren Anderson—stirred similar outrage and calls for accountability in India, but to no avail.

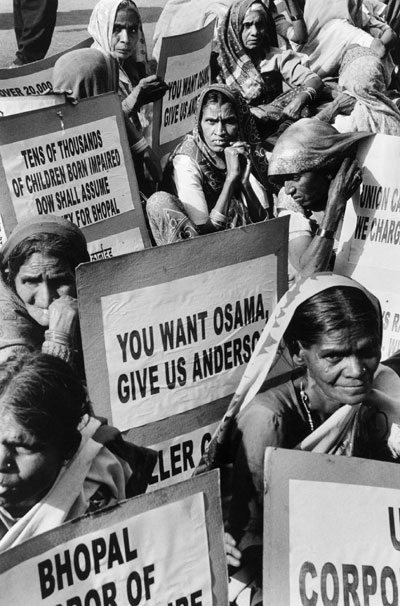

The slogan “You want Osama, give us Anderson” became one of the rallying cries for justice after the Bhopal gas tragedy of 1984, one of the world’s worst industrial disasters.

While Bin Laden was hunted down for his crimes, Anderson, the American CEO liable for the Bhopal gas disaster, was allowed to evade responsibility, sheltered by the very nation that always calls for accountability on the global stage.

Forty years ago, on the night of December 2 and 3, 1984, a toxic gas leak from the Union Carbide India Limited pesticide plant in Bhopal blanketed the city in a lethal haze. Thousands died, and hundreds of thousands were poisoned, leaving a scar that continues to haunt survivors and the city itself.

The commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Bhopal gas tragedy kicked off on November 15, 2024, with artists covering the factory’s boundary wall in striking graffiti that captured the essence of the disaster.

Just days later, on November 23, an exhibition opened in a roadside tent at JP Nagar Colony, directly across from the decaying remnants of the Union Carbide plant. The exhibition, which ran for two weeks, displayed photographs, posters, and artifacts that chronicled the devastation.

The Recipe Of The Bhopal Disaster

The Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) was a US-majority company during the 1984 disaster. UCC’s Indian branch, Union Carbide India Ltd. (UCIL), had built the Bhopal plant in the late 1960s to produce carbaryl, an insecticide, through a reaction involving methyl isocyanate (MIC)—a highly toxic compound known for its volatility.

When exposed to water, MIC reacts violently, releasing both heat and more toxic gas, making it incredibly hazardous. The plant was riddled with issues from the outset, many of which pointed to the risk of disaster. In 1976, two local trade unions raised concerns about pollution within the facility.

In 1981, a worker was fatally exposed to phosgene gas after a maintenance error. This was followed by a series of leaks, including a phosgene leak in January 1982 that exposed 24 workers and another in February 1982 when 18 workers were affected by an MIC leak.

These incidents caught the attention of local journalist Rajkumar Keswani, who began investigating the plant’s safety issues. In his reports for Bhopal’s local paper Rapat, he famously warned the public, urging, “Wake up, people of Bhopal, you are on the edge of a volcano.”

The warnings went largely ignored. In August 1982, a chemical engineer suffered severe burns after coming into contact with liquid MIC. By October of that year, another MIC leak occurred, injuring workers who attempted to stop it.

Between 1983 and 1984, numerous other toxic leaks—including chlorine, monomethylamine, and carbon tetrachloride—continued to occur. By December 1984, the plant’s safety systems had deteriorated drastically.

Most of the MIC-related safety mechanisms were malfunctioning, valves and pipelines were in poor condition, and key equipment, such as the vent gas scrubbers and the steam boiler used for pipe cleaning, had been out of service for some time. The stage was set for what would become one of the worst industrial disasters in history.

A Night Of Disaster & Suffering

On the night of December 2, 1984, a large volume of water entered a tank containing methyl isocyanate (MIC) at the Bhopal plant, which caused the MIC to heat up and boil.

Meanwhile, the plant’s cooling systems, designed to prevent such a scenario, were diverted elsewhere. As a result, MIC vapors were released into the atmosphere and spread across nearby settlements.

MIC itself is nearly odorless at concentrations that could alert people to danger, but it does cause eye irritation. Unfortunately, most residents were asleep during the night, unaware of the impending disaster.

In the span of just 45 to 60 minutes, approximately 30 tonnes of MIC escaped into the air, with the total rising to 40 tonnes within two hours. The toxic cloud drifted southeastward over the city of Bhopal.

At 12:50 a.m., a UCIL employee activated the plant’s alarm system as the gas concentration became unbearable. This should have triggered two sirens: one inside the plant and another for the public. However, the two sirens had been disconnected in 1982, allowing the internal alarm to sound while the public alarm quickly went silent after sounding briefly.

The Union Carbide Corporation has never officially confirmed which gases were released, including MIC, leaving health workers without critical information.

This lack of transparency hindered their ability to respond properly to the influx of people seeking medical attention at hospitals and clinics in Bhopal that night and the following day.

By the morning of December 3, thousands had died. The primary causes of death were suffocation, circulatory collapse, and pulmonary edema.

Autopsies revealed not only severe lung damage but also brain swelling, kidney failure, liver degeneration, and severe intestinal damage. Survivors were left to cope with long-term effects like cancer, blindness, loss of income, and financial hardship.

Some signs, such as the blood-red coloration of the internal organs of the deceased, suggested the presence of hydrogen cyanide in the fumes.

Even after four decades, the true death toll from the Bhopal gas disaster remains a matter of dispute. The central government reports 5,295 deaths, while the state of Madhya Pradesh estimates over 15,000, and the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) puts the figure at a staggering 25,000.

The long-term suffering of survivors persists, with many still grappling with the devastating health effects of the gas exposure. Meanwhile, compensation remains an agonizing mockery of the tragedy—survivors were offered a meager Rs 25,000 for lives irrevocably altered.

“You Want Osama, Give Us Anderson”

In the aftermath of the catastrophic 1984 Bhopal gas leak, Union Carbide CEO Warren Anderson was never held accountable for his role in the disaster despite allegations of corporate negligence.

Following the leak, Anderson, along with a technical team, flew to India just days after the deadly event. Although the 63-year-old executive, standing six-foot-two, intended to inspect the factory, he was discouraged from doing so by local authorities and placed under house arrest.

However, within hours, Anderson was released on bail and swiftly departed the country, never to return for trial. Reports suggest that Anderson’s swift departure was aided by high-level connections, with some alleging that the US government exerted pressure on the Indian authorities.

Arjun Singh, a senior Congress leader, later recalled that the Union home secretary had contacted him on the orders of then-Home Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao.

Moti Singh, Bhopal’s collector at the time, further revealed the circumstances surrounding Anderson’s escape. He claimed Anderson used a phone in his detention room to contact US officials, which helped him flee India.

Despite India’s repeated requests for Anderson’s extradition in 2004, 2005, 2008, and 2010, the United States rejected these efforts, a move that fueled widespread anger and led to protests demanding justice.

One iconic slogan that emerged from these protests was: “You want Osama, give us Anderson,” highlighting the frustration of Bhopal survivors who saw Anderson’s evasion of justice as a stark contrast to the US’s pursuit of international criminals. Anderson died in 2014 in the US without facing any legal consequences for the lives lost in Bhopal.

On the other hand, in 1989, Union Carbide and the Indian government reached an out-of-court settlement of just US$470 million, far below the compensation initially sought, and many victims—including children affected by the gas—were excluded from the payout.

The payment was made without delay. In 1990, the Indian Supreme Court deliberated on several appeals contesting the settlement terms.

In 2010, the Indian legal system convicted seven Indian nationals and Union Carbide’s Indian subsidiary for causing death by negligence. However, no US individuals or corporations were held accountable.

Even after various legal attempts, it remains clear that US authorities played a significant role in shielding Anderson and other key figures involved in the disaster from facing justice.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News