Will Bhutan become the 13th neighbor of China to settle the boundary disputes to the satisfaction of Beijing? The answer is not as easy as projected in the global media.

Bhutan must consider the “India factor” before agreeing with China. Any concession on its part to please Beijing that has ominous implications for India’s security will hurt Thimphu’s ties with Delhi.

Thimphu is unlikely to afford that at present. For a landlocked country like Bhutan, the hard reality is that ties with India matter more than with China.

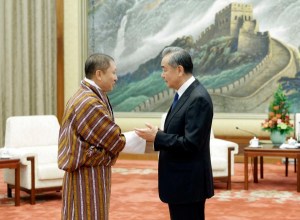

Much has been made in various media reports on the 25th round of boundary talks this week between Bhutanese Foreign Minister Tandi Dorji and China’s foreign vice-minister Sun Weidong in Beijing.

The signing by the two of what is said to be “a cooperation agreement on the responsibility and functions of a technical team for the delimitation and demarcation of the boundary” is described as a big “breakthrough.”

Is this breakthrough heading toward the eventual realization of the Chinese goal? The answer here requires a brief history of the boundary disputes between Bhutan and China.

Of China’s 14 land neighbors, Bhutan and India are the only two that have not yet resolved border disputes with Beijing. Bhutan does not even have formal diplomatic relations with China.

On the other hand, relations between India and Bhutan have been traditionally very close. The two had signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation of 1949.

Under this, India was to “guide” the foreign policy of Bhutan while assuring the latter of its sovereignty. The treaty also discussed “common security” in their relationship and allowed a security arrangement between both countries.

Accordingly, the Indian Army has been present in Bhutan and is posted on many China-Bhutan border posts.

The Indian Army maintains a training mission in Bhutan, known as the Indian Military Training Team (IMTRAT), not to speak of the exemplary work done in that country by the Border Roads Organisation, a subdivision of the Indian Army Corps of Engineers.

Besides, the Royal Bhutan Army relies on the Eastern Command of the Indian Air Force for air support during emergencies.

Above all, in 1958, the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared in the Indian Parliament that any aggression against Bhutan would be seen as aggression against India.

This assurance had come in the wake of China forcibly taking over Tibet and China’s then-Communist ruler Mao Zedong’s assertion that Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh were “five fingers” of Tibet.

Until 2007, India is said to have exercised significant leverage over Bhutan’s foreign policy, as envisaged under the Treaty of 1949. But when Bhutan transitioned from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional democracy in 2008, it was renegotiated to give greater autonomy to Bhutan in its foreign policy and military purchases.

But Article 2 of this renegotiated Treaty has emphasized that in keeping with the abiding ties of close friendship and cooperation between the two countries, “the Government of the Kingdom of Bhutan and the Government of the Republic of India shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests. Neither Government shall allow the use of its territory for activities harmful to the national security and interest of the other.”

Against this background, let us look at Chinese claims over the Bhutanese territory. Initially, the claims covered a total of 764 square kilometers – the North West (269 square kilometers), constituting the Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana, and Shakhatoe in Samste, Haa, and Paro districts; and Central parts (495 square kilometers), forming the Pasamlung and the Jakarlung valley in the Wangdue Phodrang district.

However, following the standoff between the Indian and the Chinese troops in Doklam in 2017, China extended the claims in 2020 over 740 square kilometers of the Sakteng wildlife sanctuary in eastern Bhutan for the first time, a typical tactic of Beijing in claiming more and more and later compromising to a more minor but significant demand to show its sincerity and reasonableness in settling disputes with neighbors.

This tactic has been displayed the most in China, settling boundary issues with the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Bhutan and China signed “The Guiding Principles on the Settlement of the Boundary Issues” in 1988 and “The Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the border areas” in 1998, whose Article 3 says that the status quo is to be maintained on the boundary as before March 1959. The two sides have also agreed to refrain from taking unilateral action on their border.

Incidentally, in 1996, China offered Bhutan a “resolution package deal,” proposing an exchange of Pasamlung and Jakarlung valleys, totaling an area of 495 square kilometers in Central Bhutan, with the pasture land of Doklam, Sinchulung, Dramana, and Shakhatoe, amounting to 269 square kilometers in North Western Bhutan. But Bhutan rejected it.

Many observers, including most Chinese and some Bhutanese, believe that this package deal offered by China is the best option for Bhutan, but it is not being done under Indian pressure.

It is being said that Bhutan will not mind the exchange of territories. That is why Thimpu has never complained officially over the reports of China setting up villages and undertaking infrastructural activities in “Bhutanese territory.”

Officially, Bhutan and China have held 25 rounds of boundary since 1984 and a dozen other expert group meetings that yielded the three-step road map in October 2021. Though this road map has not been publicly explained, it reportedly includes agreeing to the demarcation of the border in talks on the table, visiting the sites along the demarcated line on the ground before finally and formally demarcating the boundary between them.

However, doing that is proving to be an arduous task. Bhutan gifting Doklam to China is easier said than done. As noted, in 1996, China offered an exchange of territory with Bhutan, seeking to relinquish its claim to disputed regions in the north for Bhutan to cede a more strategically important part in the west. China is saying that the territory in the north it will forgo is far more significant than it is seeking in the west.

But then, it is not the question of the size of the area but its strategic significance. If China is particular about the West, it is because it has the Doklam plateau at the tri-junction of Tibet, India, and Bhutan. Its control would give the Chinese People’s Liberation Army a tactical advantage over India.

It is adjacent to the Chumbi valley that is only 500 kilometers from the Siliguri corridor – the chicken neck, which connects mainland India to North East India and Nepal to Bhutan. This explains the rationale behind China’s package deal offer to Bhutan.

The Chumbi Valley has enormous strategic importance for India in the sense that dominance here by China will adversely affect the stability in the Siliguri corridor, vital not only for the linkage between the Indian mainland and the north-eastern Indian states but also to ensure security for Kolkata and the north Bihar plains.

This is all the more important after China opened a railway network in August 2014 connecting Lhasa with Shigatse, a small town near the Indian border in Sikkim. China now wants to extend this lineup to Yadong, situated at the mouth of the Chumbi Valley.

And once this is done, potential threats to the Siliguri corridor from China will take a menacing proportion. Doklam under China, thus, means a Chinese dagger into Indian territory.

Therefore, India argues that any agreement over Doklam has to be trilateral, not limited to Bhutan and China.

During the military stand-off with China at Doklam in 2017, its rationale was that the 2012 agreement between the two countries was explicit that the tri-junction boundary between India, China, and third countries would be finalized in consultation with the concerned countries. Any attempt, therefore, to unilaterally determine tri-junction points is a violation of this understanding.”

Understandably, the Chinese officials and commentators are projecting India as a villain of the Bhutan-China border settlement. In this context, they quote the interview of Bhutanese Prime Minister Lotay Tshering in March 2023 with a Belgian newspaper, La Libre.

“It is not up to Bhutan alone to solve the problem. We are three. There is no big or small country; there are three equal countries, each counting for a third. We are ready. As soon as the other two parties are ready, we can discuss,” Tshering said. He had expressed hope that Bhutan and China would be able to fix some of its boundaries in a meeting or two.

This interview is open to interpretation. None other than Tshering later clarified that the interview was “misrepresented” and blown “out of proportion.” Tshering explained that he said nothing new and there was no change in Bhutan’s position.

As things stand today, Bhutan is not in a position to deny that whatever happens in Doklam is not a trilateral concern. India is important not only for its security and territorial integrity but also for its economic development and social stability.

India has consistently assisted Bhutan by funding its Five-Year Plans, hydroelectric power, and significant infrastructure projects and provided it with subsidies, grants, and currency swaps.

Following the Free Trade Agreement between the two countries, India also accounts for 90 percent of Bhutan’s imports and 77 percent of its exports. This assistance has helped Bhutan’s economy grow. Its gross domestic product rose from US$128 million in 1980 to US$400 million in 2000. By 2020, this had increased to US$2.3 billion, or nearly six times in two decades.

Indeed, this excessive dependence on India is not desirable for Bhutan in the long run. And it is understandable why young Bhutanese elites want self-sufficiency and equidistance from India and China.

But then, being a landlocked country and India is the gate to the outside world — a role that China cannot replace, as seen in Nepal — Bhutan has limited space for diplomatic maneuvers.

On its part, India realizes that the wise thing to do is not publicly reveal Bhutan’s vulnerability but maintain the status quo through seasoned, persuasive arguments through normal diplomatic channels.

It is no wonder that despite the headlines in news outlets, India has not officially commented on this week’s meeting between Tandi Dorji and Sun Weidong.

Equally important, the Bhutanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not issued any separate statement on the meetings. We have read and heard the Chinese view that “Dr. Dorji concurred with Wang on the boundary issue.”

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board – EurAsian Times and has commented on politics, foreign policy, and strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News