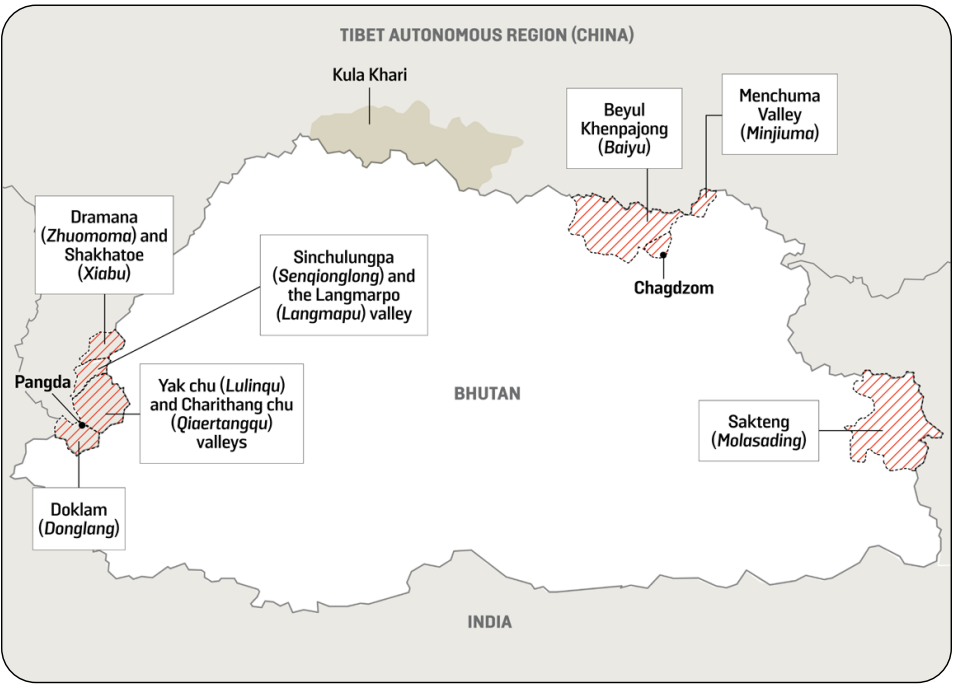

A research report reveals that China has built 22 villages and settlements within Bhutan’s traditional borders, including 19 villages and three small settlements. Three of the villages are set to be upgraded to towns. Notably, seven of these cross-border constructions have emerged since early 2023, indicating a significant acceleration in development in the annexed areas.

In 2016, China began constructing a village in a territory widely recognized as part of Bhutan. It took five years for foreign observers and governments to discover this. By then, China had already built two more villages within Bhutan’s borders, all in remote Himalayan regions.

China’s Expanding Footprint

A recent report highlights a startling development in the geopolitical landscape of the Himalayas. According to a report by ‘Turquoise Roof’ – a network of Tibetan analysts, there are now 22 such villages and settlements. Satellite imagery shows around 752 residential blocks, housing an estimated 2,284 family-sized units.

Approximately 7,000 people, along with an unknown number of officials, construction workers, border police, and military, are being relocated to these previously unpopulated areas.

These newly constructed villages are situated in high-altitude valleys and on steep ridges. They average an altitude of 3,832 meters above sea level, with ten villages perched over 4,000 meters. Menchuma, the highest village, sits precariously at an elevation of 4,670 meters above sea level.

A significant aspect of these constructions is their connectivity; all are linked by roads to Chinese towns yet remain isolated from Bhutanese urban centers.

As China strengthens its foothold in Bhutan, the latter’s military capabilities are limited. It comprises only about 8,000 personnel, primarily serving a symbolic and defensive role. This stark power imbalance raises serious concerns for Bhutan’s sovereignty amid ongoing tensions with its powerful neighbor.

A Chinese Village In Indian-Claimed Territory

China inherited Tibet’s border with Bhutan in 1951 when the Tibetan government signed a surrender agreement with Beijing, effectively ceding its territory to China.

This resulted in a border of approximately 477 km between Bhutan and China. Since then, China and Bhutan have not reached an agreement on this border, making Bhutan one of only two countries (the other being India) among China’s 14 neighbors with an undemarcated border.

China’s territorial ambitions are not confined to Bhutan. In 2021, China constructed a village in territory claimed by India, naming it “Luoba (Lhoba) New Village.”

This village is located in an area that was seized from Indian control by Chinese troops in 1959, just before the 1962 Indo-Chinese War. Since then, China has maintained full control over that territory.

China Seeks Possession Of Doklam

China is constructing cross-border villages in two primary regions of Bhutan: western and northeastern. Eight of these villages are located in western Bhutan, an area that historian Tsering Shakya notes was ceded to Bhutan in 1913 by the 13th Dalai Lama, the then-ruler of Tibet.

These villages serve strategic purposes for China, as they aim to gain control over the western region, which includes the 89-sq km plateau of Doklam.

Gaining control of the Doklam plateau would provide China with a significant strategic advantage in its ongoing tensions with India. The southern ridge (Zompelri) at Doklam overlooks the strategically vital Siliguri Corridor, which connects mainland India to its northeastern provinces.

If China gains access to this ridge, it could create a serious vulnerability for India.

India-China 2017 Doklam Standoff

Doklam, or Donglang in Chinese, is a less than 100 sq km area comprising a plateau and valley at the trijunction of India, Bhutan, and China. It lies between China’s Yadong County to the north, Bhutan’s Ha District to the east, and India’s Sikkim State to the west. China gained control of the Doklam plateau in 1988.

China claims Doklam as part of its Donglang region, but India and Bhutan recognize it as Bhutanese territory.

Despite Bhutan’s condemnation, China proceeded with its construction activities near the India-Bhutan-China trijunction in Doklam,

In June 2017, Indian and Chinese troops were engaged in a two-month standoff triggered by China’s proceeding with its construction activities near the India-Bhutan-China trijunction in Doklam despite Bhutan’s condemnation. When China attempted to extend a road southward on the plateau, Indian troops intervened to halt the construction, leading to a tense two-month border standoff.

On August 28, both sides withdrew their troops, but China has since maintained control over most of the Doklam area and built a village called Pangda there.

China’s Proposed ‘Package Deal’

China’s 14 cross-border villages and settlements are located in northeastern Bhutan, specifically in areas known as Beyul Khenpajong (including the Pagsamlung and Jakarlung valleys) and Menchuma. China has only claimed these regions since the 1980s, having marked them as part of Bhutan on official maps until at least the early 1990s.

Unlike western Bhutan, these northeastern regions hold little military or strategic value for China. So, why is China annexing north-eastern Bhutan?

China’s intent is to use these areas as leverage in exchange for territories in Bhutan’s west, particularly the Doklam plateau. This was made clear in 1990 when China proposed the “package deal,” offering to drop its claims on the northeastern areas in return for Bhutan conceding the western regions China desires, including Doklam.

The motive seems to be a bargaining strategy: China intends to exchange these territories for the desired land in western Bhutan.

China’s Six-Step Strategy To Undermine Indo-Bhutanese Treaties

However, Bhutan cannot transfer the Doklam area to China without India’s consent due to Indo-Bhutanese treaties, which require Bhutan to consider India’s security concerns. Consequently, since the mid-1990s, Bhutan has postponed agreeing to China’s proposed territorial exchange.

According to the ‘Turquoise Roof’ report, China’s reaction to Bhutan’s failure to accept the package deal has unfolded in a six-stage strategy.

First Stage: In the early 1990s, China deployed local herders into disputed areas, leading to interactions that displaced Bhutanese pastoralists.

Second Stage: Tibetan herders established huts or shelters in these contested areas.

Third Stage: Military foot patrols were sent to support the herders in these regions.

Fourth Stage: Improvised structures were built as military outposts, which were later upgraded to permanent facilities.

Fifth Stage: From around 2004, roads were constructed to connect these outposts to towns within Tibet (China).

Final Stage: In 2016, the construction of villages commenced in the claimed territories.

If Bhutan Accepts China’s Demands…

In March 2023, the Bhutanese government, seemingly left with little choice, indicated that it was nearing a deal with China involving a territorial exchange.

However, China’s construction of cross-border villages has not only continued but accelerated; since early 2023, seven more villages or settlements have been built in north-eastern Bhutan, significantly increasing the housing stock in the region.

It appears increasingly unlikely that China will fulfill its original offer to return land in north-eastern Bhutan, where it has constructed villages. Bhutan is likely to regain only those areas that China has claimed or annexed primarily as leverage to create the appearance of concessions.

Analysis of China’s construction surge in 2023-24 suggests that China is now very unlikely to return areas where it has built villages, encompassing about 80% of the disputed territory it has annexed.

“China is expected to argue that it is not obligated to return these areas because Bhutan, constrained by India’s security concerns, is unlikely to yield the Doklam region,” according to the report.

If Bhutan, as anticipated, concedes the non-Doklam areas along its western border to China, the latter is likely to relinquish its claims only to areas it has claimed but not annexed, totaling approximately 353 sq km in the Upper Langmarpo, Charitang, and Yak Chu regions in the west, and about 78 sq km in the Chagdzom area in the northeast.

China is also likely to return an area of about 147 sq km that it has occupied but has not developed with villages or relocated settlers, specifically in the Pagsamlung Valley.

The report also says that, given Bhutan’s limited defense resources and India’s historical role as Bhutan’s security guarantor, there has been little interest from India regarding Bhutan’s border issues beyond Doklam. Very little, if anything, is known about discussions between India and Bhutan concerning the Bhutan-China border dispute since 2017, and India’s position on Bhutan’s border issues, other than Doklam, remains unclear.

The Challenge For Small Nations

China’s cross-border village strategy raises significant concerns not only for Bhutan and India but also for the international community, as it sets a troubling precedent for how major powers can exploit territorial claims to expand their influence at the expense of smaller states.

Bhutan’s struggle to effectively respond to China’s opportunistic annexation efforts underscores the challenges smaller nations face when confronting powerful adversaries. This issue is similarly evident in the situations involving China and Taiwan, as well as China and the Philippines in Asia.

The current situation emphasizes the need for enhanced diplomatic support and a robust framework to safeguard the sovereignty of small nations and ensure they are not left vulnerable to the encroachments of larger powers.

- Shubhangi Palve is a defense and aerospace journalist. Before joining the EurAsian Times, she worked for ET Prime. In this capacity, she focused on covering defense strategies and the defense sector from a financial perspective. She offers over 15 years of extensive experience in the media industry, spanning print, electronic, and online domains.

- Contact the author at shubhapalve (at) gmail.com