The government of India’s Forward Policy did not leave soldiers in poorly defended and armed ‘penny packets’; the military planning was free of political interference; the late Brigadier JP Dalvi was in a position to effectively defend Namka Chu from the advancing Chinese.

These are some contrarian facts published in a book on the 1962 Indo-China war. ‘The 1962 India-China War – What They Don’t Want You To Know’ by Sandeep Mukherjee refers to parts of the yet-to-be-declassified Henderson Brooks Report (HBR), the official history of the war by the Ministry of Defense (MoD) and published interviews with former People’s Liberation Army (PLA) officers. Mukherjee is an expert in military history, particularly World War 2.

With a foreword written by retired Maj Gen K. Khorana and coming amidst renewed tensions with China in Arunachal Pradesh, the book sheds new light on India’s humiliating defeat at the border war that scarred the military and political landscape for decades.

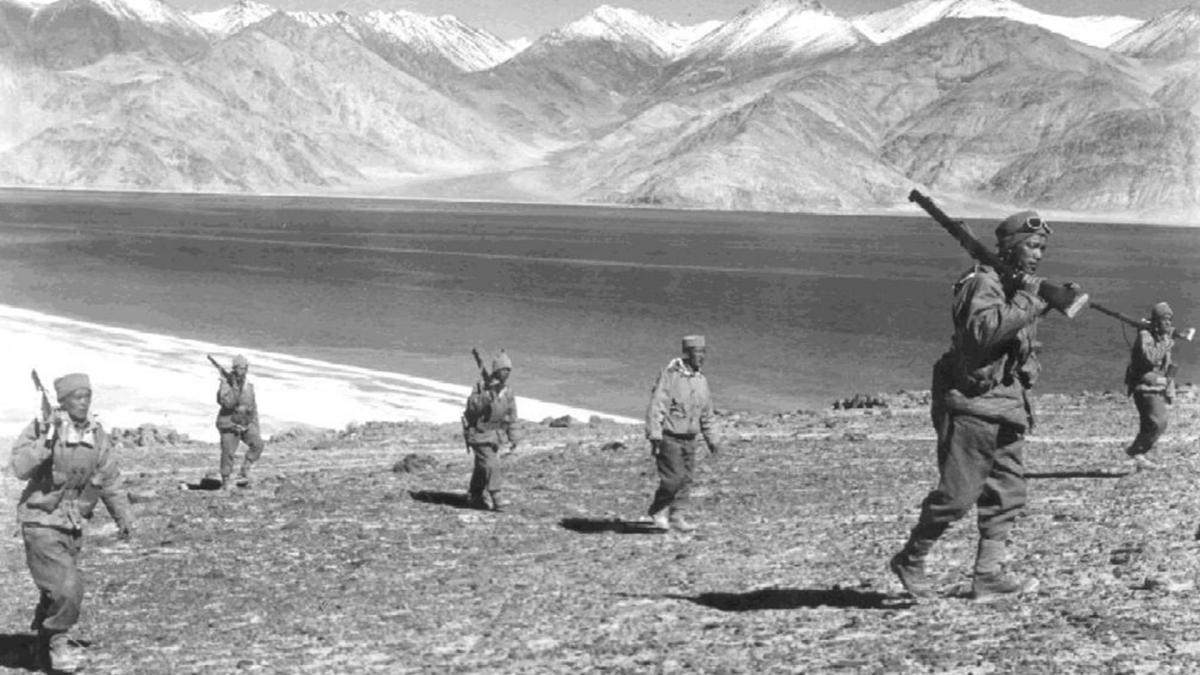

The book focuses on the Battle of Namka Chu in the then North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA, present-day Arunachal Pradesh) on October 20, where the 7th Brigade (or 7 Brigade) commanded by Brig Dalvi was wiped out and the Chinese took him prisoner. He was repatriated in 1963.

What Really Happened At Namka Chu?

Dalvi’s 1968 book ‘The Himalayan Blunder: The Curtain Raiser to the Sino-Indian War of 1962’ maintained that the Indian Army was ill-equipped and was forced into fighting and aggressively resisting the Chinese.

Three other important figures were then Army chief General PN Thapar, Eastern Army Commander Lt Gen LP Sen, and commander of the 4 Corps, Lt Gen BM Kaul.

Under late Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the government of India’s Forward Policy amply provided for strong operational military reserves in the rear areas to support the forward posts. The Army, however, deleted the bit in its order handed down to its lower formations.

The book quoted an excerpt from the Henderson-Brooks Report (HBR), which is still to be officially declassified. It said Nehru had directed “efforts (to be) made to position major concentration of forces along our borders in places conveniently situated behind the forward posts from where they could be maintained logistically and from where they can restore a border situation at short notice.”

“(Thapar), along with Sen and Kaul, knew they had not made any provisions for the creation of the logistic and operational bases in support of the forward posts, as had been originally instructed by the government,” Mukherjee writes in the book.

Moreover, he quotes Nehru from another official record, where the former PM said, “(If) the commander on the spot so felt (that) the odds were against us…we should hold on to present positions instead of attacking.” This runs contrary to the narrative that the political leadership imposed a suicidal course of action on the military.

On the day of the battle (Namka Chu), the common claim goes that the Indian Army, especially Dalvi’s 7 Brigade, was overwhelmed. The Chinese ran over Indian positions because there were no personnel and equipment resources.

But only one Battalion, the 2 Rajput (discussed subsequently), was fully engaged and overwhelmed – not because of lack of ammunition, but because they were surrounded overnight.

The right flank of Dalvi’s defenses, which consisted of the 9 Punjab and the 4 Grenadiers, had been only partially engaged on the morning of the 20th. Only the B Company of the 4 Grenadiers had taken casualties.

The 7th Brigade also had a heavy mortar detachment on the Tsangdhar Ridge, which could have been used to hit the Chinese.

“The 7th Brigade had three-and-a-half Battalions under it. But Dalvi failed to organize a credible tactical defense that could have easily halted the Chinese,” Mukherjee said while speaking to the EurAsian Times. He distinguishes between no resources/ammunition and less firepower.

“For instance, there were 60 mortar shells that were not at all used, while only some of the 80 artillery rounds were fired. If an attempt would have been made to lay out a tactical defense, the ammo would have begun running short later. The 7 Brigade could have held out longer, inflicted huge casualties on the Chinese, and might have also been resupplied,” Mukherjee explains.

Moreover, mountainous terrains usually favor the defenders, in this case, India, where an attacker (China) needs a manpower ratio of 3:1. This means there should be three Chinese soldiers for each Indian soldier. “But Chinese had only a 2:1 ratio. This offered the Indian defenders a concrete chance to stall and bloody their advance even with limited resources, by neatly arranging defenses and exploiting the mountainous terrain,” Mukherjee said.

Mukherjee’s conclusion on the 7 Brigade’s reasonable situation is ironically bolstered by praise from the former PLA Political Commissar (PC), who described the 7 Brigade as an “elite unit.” Lt Gen Yin Fa Tang, the PC of the Tibetan Army’s Formation 419, was interviewed in the Military History magazine of the Academy of Military Sciences in 2005.

“To be honest, the Indian Army was still very capable of fighting,” Yin said.

Skipping The Action – Lack Of Faith?

Other Indian Army units and officers simply disappeared from action, which Mukherjee has conjectured was because Dalvi failed to support them in a previous engagement with the Chinese. Through the official history, Mukherjee shows that 9 Punjab and the two Companies of 4 Grenadiers were not to be found for nearly one-and-a-half days.

This is because they were asked to withdraw by noon on the 20th to Hathung La but reached it only the next day (October 21) by 6 pm, by when they were taken prisoner by the Chinese there. The distance to Hathung La was just a few hours climb which they should have reached by evening the same day.

The Chinese could also not have interfered with their withdrawal since the latter did not press any attack at Hathung La until 5 am the next day (October 21). There are no records of their whereabouts in the period and their reason for absence from the fight.

Another case was that of 1/9 Gurkha’s ‘A’ Company Commander, Major AG Minwalla, who escaped into Bhutan. The GoI’s official history says Minwalla abandoned his men at Nelum upon spotting Chinese on Bridge Five.

“He did not return to Nelum, where he had left the other platoon soldiers but crossed into Bhutan. The men at Nelum were left to care for themselves,” an excerpt of the MoD’s official history in the book said. Mukherjee says Minwalla did not even send a ‘runner’ to inform his Platoon. Colonel AA Athale and Dr. PV Sinha wrote the official history in 1992.

Minwalla’s, 9 Punjab’s, and 4 Grenadiers’ seemingly inexplicable inaction was actually “utter demotivation and lack of faith” in support from Dalvi, which they had experienced ten days prior, according to Mukherjee.

On October 10, 9 Punjab had “fought valiantly” against 800 Chinese with just 50 men at Tseng Jong but did not receive medium machine gun (MMG) and mortar support from Dalvi. Seventy-seven Chinese were killed in that engagement.

Rookie Mistakes

Two instances also disprove Himalayan Blunder’s “no ammunition” claim. Jemadar Mohanlal, in charge of the medium machine-gun (MMG) Platoon of 6 Mahar, was quoted as possessing 12,000 rounds of ammunition in the official records. He was however disallowed from firing on the vulnerable Chinese troops attacking 9 Punjab’s men at Tseng Jong.

Another is the case of the 2 Rajput Battalion, which also signified poor tactical planning on the part of the 7 Brigade, besides challenging the “no ammunition” charge. For one, the 2 Rajput was positioned in an elementarily flawed single defensive line (or ‘line abreast’) without any tactical defensive positioning in its depth areas. The four Companies of the 2 Rajput were between Bridge 3 and Temporary Bridge.

Mukherjee pointed out how no basic tactical field practices, like surveying the local geography that could have revealed the Namka Chu river to have frozen or sending out night patrols, were undertaken.

The Chinese crossed the frozen Namka Chu river by walking over it overnight, went behind the 2 Rajput’s four Companies, and positioned themselves in the jungles. They attacked in the morning, surrounding 2 Rajput from all sides, who fought valiantly.

This too eliminates the claim of an ammunition shortage. Had the 2 Rajput run out of ammunition, they wouldn’t have been able to fight and would have surrendered.

To put matters in perspective, the distance between the Temporary Bridge and Bridge Five was a whopping 10 kilometers. The Chinese just walked through undetected in the night because there were no patrols. Out of roughly 500 men, more than 200 were killed, and the rest were either wounded or captured.

Maj Gen K. Khorana wrote in his foreword to the book how “senior officers wrote personal accounts and exonerated themselves of any responsibility for the disastrous outcome.”

Former Northern Army commander Lt Gen HS Panag’s short review published on the book cover, notes the “ambiguous political directions and military orders, inadequate preparations and non-tactical defenses…was a disaster waiting to happen.”

Thus, Panag, too, seems to acknowledge that the 7 Brigade was in a position to halt the Chinese advance, going on to call the book an “outstanding and authentic historical account.”

Speaking to EurAsian Times on the long-running India-China border disputes, Panag said how China’s rapid economic development to become the second largest economy in the world allows it to exert its territorial claims and foreign policy assertively.

“This is happening because we have no Comprehensive National Strength (CNP), whereas China does,” he adds.

- The author can be reached at satamp@gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News