In a recent development, Indian security forces eliminated three Naxalites, including a woman, during an encounter near the Chhattisgarh-Maharashtra border in the Abuzmad area.

This incident has pushed the total number of Naxalites killed in 2024 to 157, marking the highest number of Maoist fatalities in the past 15 years. Additionally, authorities have arrested approximately 663 Naxalites, while 656 have surrendered this year.

Among the slain was Rupesh, a member of the Dandakaranya Special Zonal Committee (DKSZC), who was killed on September 23 during an anti-Naxal operation by a joint security team.

Rupesh, who led Maoist Company No. 10 and operated in the Gadchiroli area of Maharashtra, had a bounty of ₹25 lakh ($30,000) on his head. Another Naxalite, Jagdish, a divisional committee member from Balaghat, Madhya Pradesh, had a reward of ₹16 lakh ($20,000). The forces recovered an AK-47, an SLR, an INSAS rifle, a 12-bore gun, explosives, and Maoist paraphernalia from the encounter site.

Heightened Anti-Naxal Operations

The BJP-led central government has significantly ramped up anti-Naxal operations since regaining power in Chhattisgarh last year.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah has set an ambitious goal, vowing to “totally eliminate Left Wing Extremism (LWE) and Naxalism from the country in two years” during the 2024 Lok Sabha election campaign.

In line with this objective, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) has deployed four battalions, comprising over 4,000 personnel, to the worst Naxal-affected areas of Bastar in Chhattisgarh. This strategic move aims to resolve the Maoist issue by March 2026, aligning with Shah’s declaration of a “strong and ruthless” plan to eradicate Left Wing Extremism in India.

Internal Security Challenges For India

India has been dealing with three variants of the Internal Security challenge for decades, and each has its own complexities — a proxy war and terrorism in Kashmir, sub-national separatist movements in the Northeast, and the Naxal-Maoist Insurgency in the Red Corridor.

Left-Wing Extremism, also known as the Naxal or Maoist insurgency, has been a persistent internal security challenge for India for five decades.

The Left Wing Extremism (LWE) or Naxal insurgency in India originated in a 1967 uprising in Naxalbari, West Bengal, by the Communist Party of India (Marxist). These people believe in political theory derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong.

The movement sought to address the resentments of marginalized communities, including poor farmers and landless laborers, against feudal landlords and the state. It was fueled by widespread poverty, social inequality, and discontent with government policies. The Naxalites sought to establish a “people’s government” through armed struggle.

Many Naxalite leaders have expressed respect for Mao’s strategies, advocating for armed struggle to achieve social and economic justice. The Chinese Communist Party’s historical support for various revolutionary movements has inspired Naxal leaders to adopt similar strategies to gain power.

Reports suggest that some Naxalite factions have received training and logistical support from external sources, including groups sympathetic to Maoist ideologies that may have connections to China. This support often manifests through the transfer of arms, training in guerrilla warfare, and the sharing of tactics employed during the Chinese Revolution.

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) reports that naxalism is primarily restricted to nine states: Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Telangana, and West Bengal.

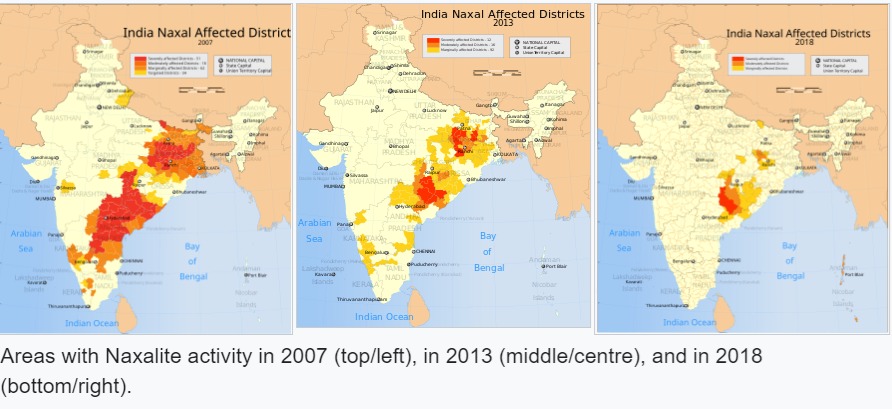

The geographical spread of Left Wing Extremism (LWE) violence has significantly decreased, from 126 districts in 10 states in 2013 to just 38 districts in nine states by April 2024.

Chhattisgarh: The Epicenter of Naxal Activity

Naxalite activity is particularly concentrated in several regions, including approximately 15 districts in Chhattisgarh, seven in Odisha (Kalahandi, Kandhamal, Bolangir, Malkangiri, Nabarangpur, Nuapada, and Rayagada), five in Jharkhand (Giridih, Gumla, Latehar, Lohardaga, and West Singhbhum), three in Madhya Pradesh (Balaghat, Mandla, and Dindori), two in Kerala (Wayanad and Kannur), two in Maharashtra (Gadchiroli and Gondia), and two in Telangana (Bhadradri-Kothagudem and Mulugu).

Chhattisgarh, a central Indian state bordering seven others – Uttar Pradesh to the north, Madhya Pradesh to the northwest, Maharashtra to the southwest, Jharkhand to the northeast, Odisha to the east, and Andhra Pradesh and Telangana to the south – remains the most affected by Naxalite activities.

Of its 33 districts, 15 are currently grappling with the Naxalite menace, including – Bijapur, Bastar, Dantewada, Dhamtari, Gariyaband, Kanker, Kondagaon, Mahasamund, Narayanpur, Rajnandgaon, Mohalla-Manpur-Ambagarh Chowki, Khairgarh-Chhuikhadan Gandhi, Sukma, Kabirdham, and Mungeli.

Social Issue or Security Threat?

The approach to tackling Naxalism often sparks debate: should it be viewed primarily as a social issue or a security threat?

“The fight against Naxalism is not just a fight of ideology but also of areas which are lagging behind due to lack of development,” said Amit Shah at a press conference following a review meeting on Left Wing Extremism (LFW) in August 2024.

Individuals without sustainable livelihoods are often vulnerable to recruitment by the Naxalite movement. The Maoists take advantage of this vulnerability by offering weapons, ammunition, and financial support.

The Bandyopadhyay Committee (2006) identified poor governance, economic disparities, and socio-political discrimination against tribal communities as primary drivers of Naxalism, recommending tribal-friendly land acquisition and rehabilitation to address these issues.

Local Mining: A Contentious Issue

Mining activities in Naxal-affected areas remain a significant point of contention.

For example, mineral research institutes have reported the presence of high-quality iron ore in Surajgarh, located in Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra, since the 1960s. However, due to the influence of Naxalism, officials have been unable to access the area, and no iron ore was extracted until 2015.

Protests against mining activities included the killing of Jaspal Singh Dhillon, a senior manager at Lloyds Metals, as well as arson and the distribution of leaflets and banners by Naxalites.

Local tribal communities have also voiced strong opposition to these projects. For nearly two years, they have protested against around 25 mining operations, including the Surjagad Ispat Private Limited iron and steel factory.

Despite the government conducting a Bhumi Pujan in July after quelling local dissent, many residents remain unconvinced.

The project is projected to produce four million tonnes of steel and create jobs for 80 percent of the local population. While the government promotes mining projects as sources of employment and development, many local residents remain skeptical.

They continue to demand essential services such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, and sustainable employment opportunities for their communities.

Conclusion

The Naxalite conflict in India presents a complex challenge that intertwines security concerns with socio-economic issues. As the government intensifies its efforts to eradicate Left Wing Extremism, addressing the root causes of the movement and balancing development with the needs and concerns of local communities will be crucial for achieving lasting peace and stability in the affected regions.

- Shubhangi Palve is a defense and aerospace journalist. Before joining the EurAsian Times, she worked for E.T. Prime. In this capacity, she focused on covering defense strategies and the defense sector from a financial perspective. She offers over 15 years of extensive experience in the media industry, spanning print, electronic, and online domains.

- Contact the author at shubhapalve (at) gmail.com