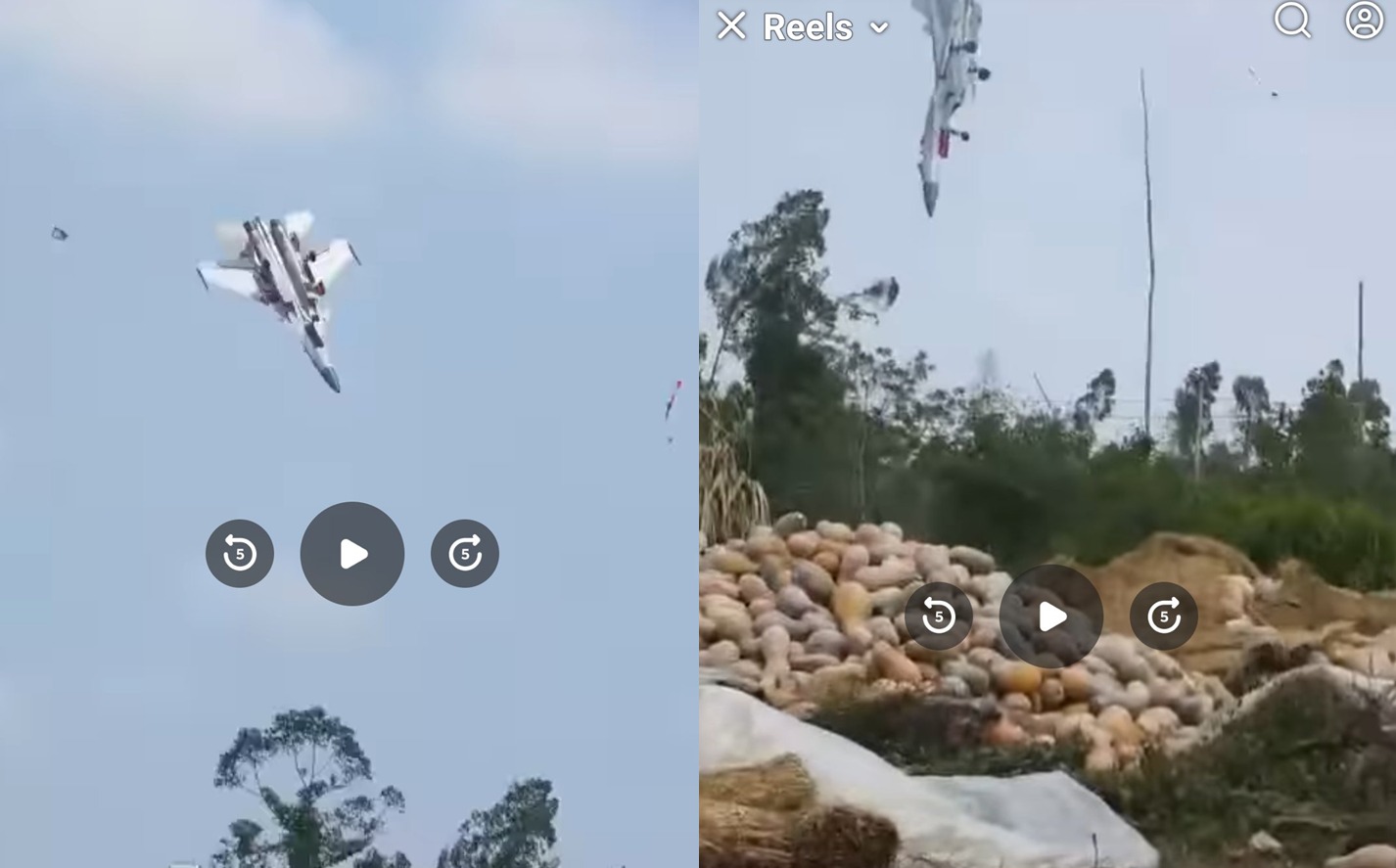

The crash of a Chinese Navy J-15 “Flying Shark” fighter jet on March 15 during a routine training exercise near Jialai Town in Lingao County, Hainan Province, has reignited scrutiny of China’s military aviation program.

While the pilot ejected safely and there were no reported casualties on the ground, the incident raises questions about the reliability of the aircraft and its components.

This latest crash is not an isolated event but a continuation of longstanding issues affecting China’s quest for self-reliance in military aviation.

Tracing J-15’s Troubles

The J-15, developed by Shenyang Aircraft Corporation, is a carrier-based multirole fighter that entered service in 2013. It was reverse-engineered from the Russian Su-33 after a prototype was acquired from Ukraine in 2001.

Touted as a cornerstone of China’s naval aviation capabilities, the aircraft was intended to project power in contested maritime areas like the South China Sea. However, its heavy airframe has consistently limited its payload and combat radius, diminishing its multirole effectiveness, especially in comparison to the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18 Super Hornet.

The J-15 also holds the unpleasant distinction of being the heaviest carrier-based fighter in service. The J-15 weighs 38,000 pounds at empty weight, almost 6,000 pounds more than the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and 4,000 pounds more than the F-35C.

Compounding these design limitations is the J-15’s reliance on the domestically produced WS-10 turbofan engine, a recurring weak point across China’s fleet.

The WS-10, developed by the Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC), was introduced to reduce reliance on Russian imports.

Initially envisioned as a breakthrough in indigenous aviation technology, the engine has been plagued by material deficiencies, quality control lapses, and insufficient testing. These challenges have not only affected the J-15 but also other aircraft in China’s fleet.

The WS-10 Engine: A Systemic Problem

The WS-10 engine is central to the challenges faced by China’s military aviation, consistently undermining the reliability of key platforms.

For example, the Chengdu J-10, a single-engine multi-role fighter, has suffered multiple accidents attributed to engine failures. In one instance, a J-10 lost power mid-flight and crashed into a river, with the pilot narrowly escaping harm.

Early J-10 models were equipped with Russian AL-31FN engines, but the later transition to the WS-10A failed to resolve reliability concerns as the engine continued to experience power losses and mechanical failures.

Similarly, the Shenyang J-11, a twin-engine air superiority fighter based on the Russian Su-27, has faced operational setbacks due to the WS-10. Although its twin-engine configuration provides a safety net, the J-11 has encountered issues during high-intensity training exercises.

The J-16, an advanced twin-engine fighter derived from the J-11, has also been affected, raising serious concerns about the long-term operational viability of platforms relying on the WS-10.

Even international operators have experienced challenges. On June 5, 2024, a Pakistan Air Force (PAF) JF-17 Block 2 crashed in Punjab’s Jhang district, the fifth such incident in 13 years. While this aircraft is equipped with Chinese RD-93 engines, its maintenance difficulties and structural vulnerabilities, including cracks in guide vanes and exhaust nozzles, echo problems within China’s broader engine development program.

Limited Combat Experience

Another significant challenge for Chinese military aviation is the limited combat experience of its pilots and platforms compared to their American counterparts.

While Chinese pilots regularly undertake training missions, such as incursions into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone, as part of their “grey zone warfare” strategy, these remain simulated exercises.

Similarly, their patrols across northeast Asia fail to match the extensive wartime experience accumulated by American pilots flying aircraft like the F-22, F-35, and F-16.

Broader Implications and Expert Perspectives

In an op-ed for the EurAsian Times, Air Marshal Anil Khosla (Retired) highlighted the broader implications of China’s struggles with engine technology. He wrote, “Building a reliable aero-engine requires far more than investment; it demands decades of experience, cutting-edge research, and robust supply chains.”

Khosla argued that the WS-10’s shortcomings not only undermine the operational readiness of platforms like the J-15 but also expose deeper gaps in China’s ability to achieve true self-reliance in critical defense technologies.

International experts share similar concerns. A report by the RAND Corporation shows the dichotomy, stating: “China’s ability to produce advanced airframes is impressive, but its engine technology lags behind Western and Russian standards, creating a bottleneck in its broader modernization goals.”

Another issue lies in upgrading and modernizing these aircraft.

As Warrior Maven notes, “The upgrades may include increasing the number of air-to-air missiles the fighter can carry in its low-observable configuration, installing thrust-vectoring engine nozzles, and adding supercruise capability by installing higher-thrust Indigenous WS-15 engines.”

Balancing Aspirations With Reality

Despite these challenges, China continues to innovate. The introduction of newer aircraft like the stealth-capable J-35 and upgraded versions of the J-15 suggests ongoing efforts to address these shortcomings.

However, incidents like the recent crash highlight the risks of relying on platforms still grappling with fundamental design and performance issues.

Balancing its ambitious aspirations with its current capabilities remains one of the most significant hurdles for China’s defense industry.

- Penned By: Mohd. Asif Khan, ET Desk

- Mail us at: editor (at) eurasiantimes.com