Japanese government officials and representatives of four domestic startups in emerging technologies with potential defense applications met in Tokyo on Sep. 6. It was to discuss ways to help the fledgling companies working on drones and robots.

The Japanese government has compiled a list of 200 startups with promising defense-related technologies.

In a country where giant conglomerates arguably produce the world’s finest consumer electronics, optical fibers, automobiles, copy machines, facsimiles, and visual media, among others, startups intending to enter the defense sector with the government’s help may look very ordinary.

But, on closer scrutiny, it implies a bright future for the Japanese defense industry, which, at the moment, appears to be way behind its counterparts in other developed countries.

What is more important to note here is that unlike its other industries, which have the exclusive Japanese stamp, Japan is prepared to produce, rather than co-produce, arms with its allies and partners.

This, perhaps, is one of the reasons why Western arms suppliers have started shifting their Asian HQs from countries like Malaysia and Singapore to Japan.

The Japanese defense market is going to be very big, with the present government led by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida determined to have the world’s third-largest military budget by 2027, thanks to the ever-rising threats from China, not to speak of the growing North Korean missiles and nuclear weapons.

Japan’s defense ministry requested a nearly 12% budget increase last week. The record US$52.5 billion request for the 2024 fiscal year marks the second year of a rapid five-year military buildup under a new security strategy that Kishida’s government adopted in December.

Over the next five years, Japan plans to spend US$315 billion. That means Japan is doubling its annual spending to around US$68 billion to emerge as the world’s third-biggest spender after the United States and China.

Japan has the world’s tenth-largest defense expenditure, trailing South Korea, Germany, France, the UK, Saudi Arabia, India, Russia, China, and the US. Japan’s defense spending is now slightly more than 1% of its GDP. This is to rise to 2% of the GDP of the world’s third-largest economy, Japan.

On December 16, 2022, Kishida’s government released three significant national security and defense-planning documents: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program (DBP).

These three security documents provide a blueprint that could fundamentally reshape Japan’s approach to defending itself and its security relationship with allies, including the United States.

The documents label China as an “unprecedented strategic challenge,” declare Japan’s intention to develop a “counterstrike” capability to attack enemy missile sites, and outline plans to increase Japan’s security-related expenditures to 2% of its national gross domestic product (GDP), in line with NATO standards.

As is well-known, Japan and the United States have a mutual defense treaty (1951) that grants the latter the right to base its troops — currently numbering over 50,000 — and other military assets on Japanese territory in return for a pledge to protect the former.

Japan pays roughly US$2 billion annually to defray the cost of stationing US military personnel in its territories. In addition, Japan pays compensation to localities like Okinawa hosting US troops, rent for the bases, and the costs of new facilities to support the realignment of American forces.

This security relationship between the two countries was based on what was said to be the concept of the “Spear and Shield” division of labor. The United States is the “spear,” providing the power projection capabilities, and Japan is the “shield,” focusing on strictly defensive operations.

Accordingly, Japan’s military was named the Self Defense Forces (SDF), which, under the country’s pacifist constitution drafted by the US after the end of World War II, is prohibited from fighting a war.

This constitution prohibits Japan from making or producing “offensive weapons.” Until 2014, Japan was barred from exporting even its “defensive weapons.” This spear and shield model was a big handicap for Japan in developing an advanced defense industry that one sees in NATO allies of the US.

However, things have been changing since the beginning of this century. Both the US and Japan have agreed to improve the operational capability of the alliance as a combined force.

The US has encouraged Japan to undertake defense reforms by reforming its political and legal constraints. It wants Japan to make its military more capable, flexible, and interoperable with American forces.

It was against this background that the Kishida government released the three security documents that provided a blueprint that could fundamentally reshape Japan’s approach to defending itself and its security relationship with the United States.

The DBP aims to attract new entrants and established players in the defense industry “by improving the longer-term predictability of procurements, offering subsidies for industrial facilities and cyber defenses, and strengthening information and industrial security.”

The DBP seeks to enhance Japan’s defense-technology base “by tightening deadlines on R&D in line with the country’s acquisition requirements, promoting new R&D initiatives with foreign partners, adopting international requirements (replacing Japan-specific ones) and including non-defense technologies for R&D.”

While attempting to reestablish the country’s domestic defense manufacturing, the DBP also emphasizes self-reliance and defense export promotion (which was banned in 2014). The DBP allows equipment transfers to build international partnerships critical to expanding Japan’s defense industrial base.

The idea is that Japan’s growing international defense and security partnerships and defense-related bilateral relationships will create market expansion opportunities for domestic industry participants in allied nations and vice versa. So, synergistic partnerships focusing on technology share and transfer between foreign and domestic companies will be welcome for the industry growth.

As it is, Japan has recently expanded its security cooperation with Australia, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, and India, with the encouragement of the US government. Although not as developed or formalized as the US treaty alliance, these burgeoning relationships indicate efforts by Japan to diversify its defense partnerships beyond the one with the United States. The US does not mind that.

Committed to working with allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific to deal with a rising but hegemonistic China, the US is now encouraging increased defense collaborations among these allies bilaterally and multilaterally, apart from joint planning, joint exercises, and joint training.

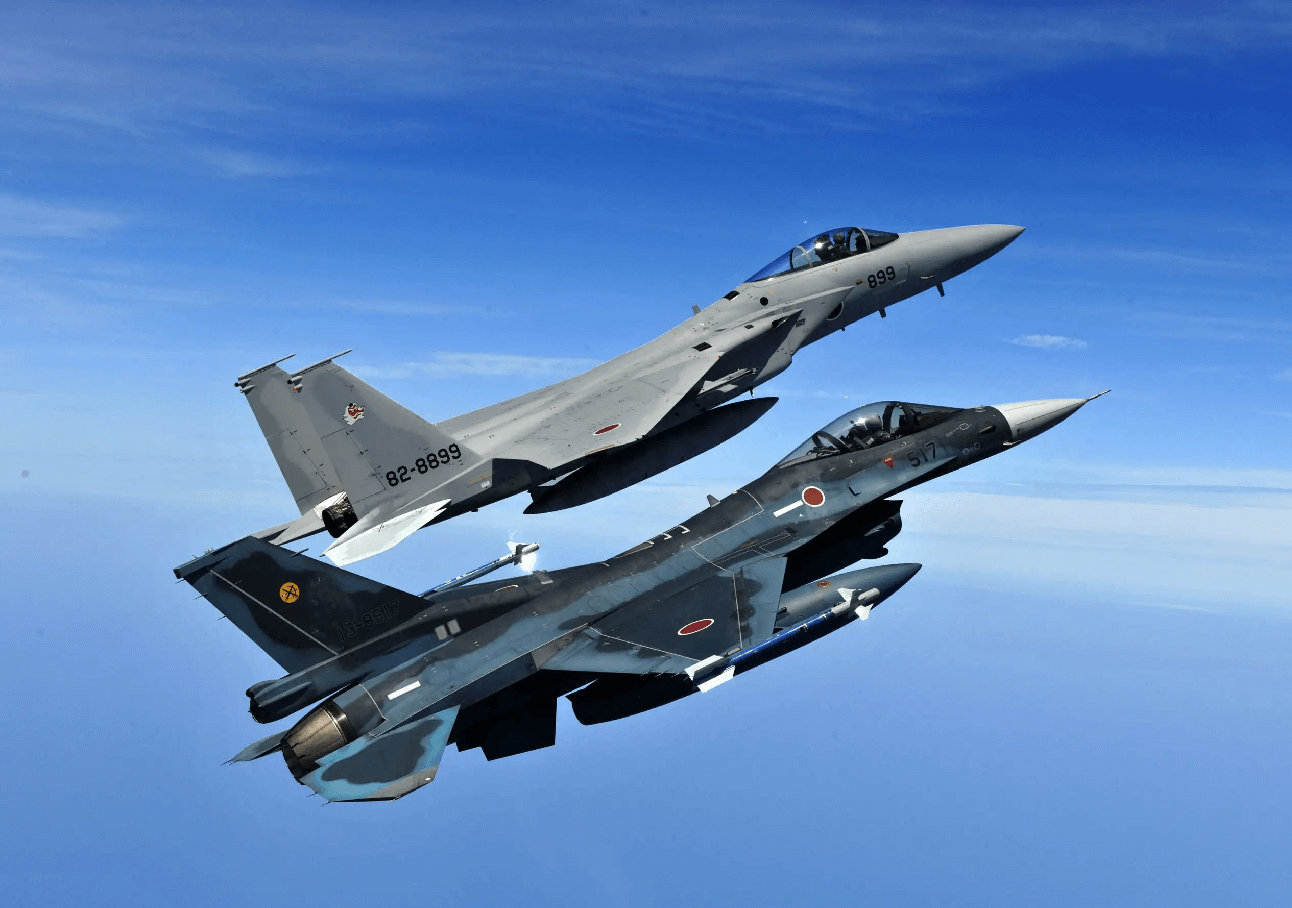

This new outlook change is evident from how Japan plans to build its next-generation FX fighter aircraft in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Italy under a “Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP).” UK’s BAE Systems, Leonardo, MBDA, Rolls-Royce, and its ministry of defense, Japan’s IHI Corporation, Mitsubishi Electric’s and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries; and Italy’s Avio Aero, Elettronica and Leonardo are all parts of this joint effort.

Both QUAD partners, Japan and Australia, are also discussing similar collaborations and co-production. Even India and Japan, as QUAD partners, are mooting the idea of “co-innovation, co-design, and co-creation for a deeper and mutually beneficial defense cooperation” in next-generation warfare equipment and systems.

Last year, Indian Defense Minister Rajnath Singh and his Japanese counterpart Yasukaza Hamada acknowledged the importance of bilateral defense cooperation and partnership and its critical role in ensuring a free, open, and rules-based Indo-Pacific region.

Accordingly, the two countries are said to have taken five initiatives: An agreement concerning defense equipment and technology transfer; a Joint working group on defense equipment and technology cooperation (JWG-DETC); Cooperative research on Augmentation Technology for Unguided Vehicles (UGV)/robotics; Japan India cyber dialogue to review policy and strategic planning for security; and an MoU regarding space cooperation for surveillance and situational awareness.

Of course, many experts believe it will take quite some time for the Japanese defense industry to be a global brand like its electronic or automotive counterparts. Protectionist domestic laws in many areas in the defense sector still need liberalization to attract investment. Besides, the defense industry does not give quick returns to begin with. It will be low profitability for some years.

And then there are “cross-cultural problems.” As Robert Moss, senior director of sales and business development in the Asia-Pacific for US-based Teledyne FLIR Defense, says, “Unfortunately, many US companies — particularly defense companies — join into their business outside of the United States with the same norms and ideas that they bring to the United States and DoD. And that doesn’t work in a country like Japan.

“It doesn’t work in a country like India. It doesn’t work in many places. Conversely, Japanese companies have to understand where those American or European companies are coming from — what their thought process and norms are.”

For Ross, not understanding cultural norms “are going to be points that stop you from doing business smoothly and efficiently and being welcomed into that business culture.”

Admittedly, there are problems. But that does not mean that those cannot be overcome. It is undeniable that Japan’s DBP is marked by historic resourcing and policy shifts aimed at responding to the security challenges in the Indo-Pacific. The DBP states, ” Japan will emphasize the defense production and technology base, characterized as a virtually integral part of a defense capability.”

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board – EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, and strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News