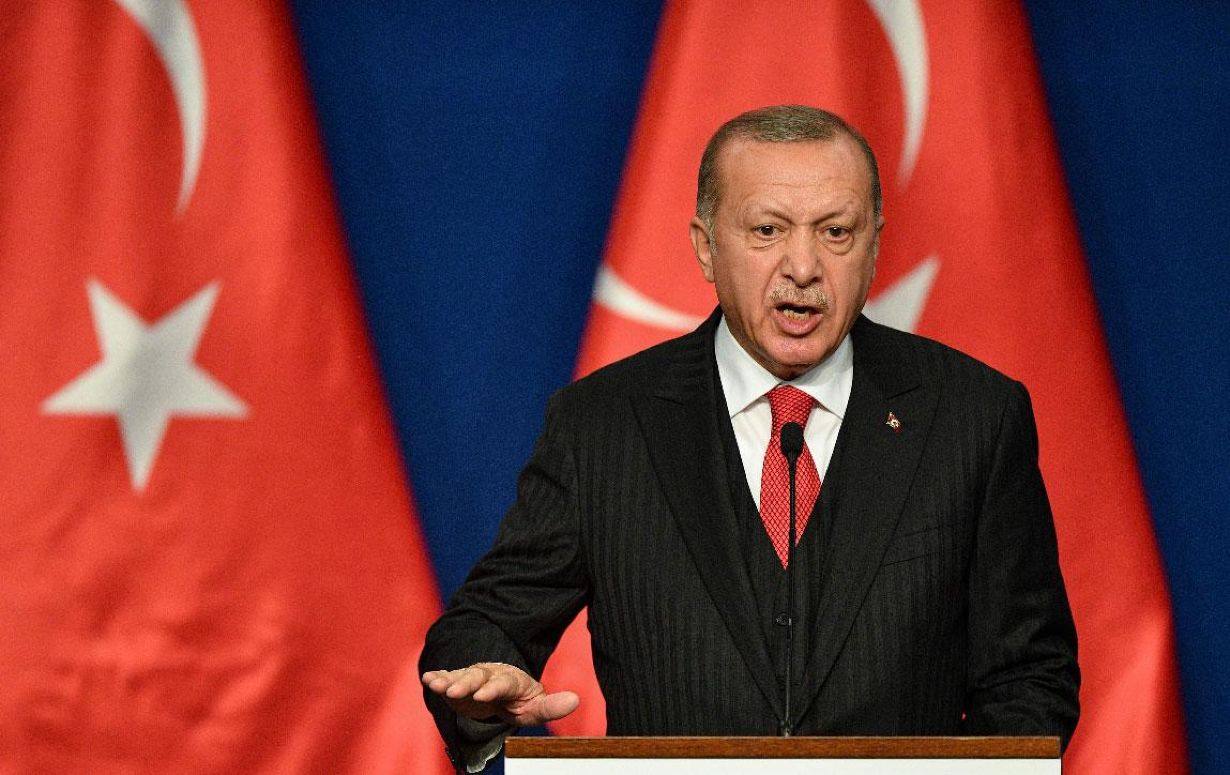

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s volte-face on Sweden’s accession to NATO has brought him into the good books of the multilateral security alliance.

Rafale Fighters ‘Go Missing’ In Official Statements Of Both India & France; Is Indian Navy Really Getting Rafale-M?

Now the US has set in motion the transfer of 40 F-16 fighter jets to the transcontinental country. However, Erdogan’s political maneuvering has not been enough to get Ankara back into the F-35 Lightning II joint strike fighter jet program.

The S-400 surface-to-air missile system acquired by Turkey has been the reason why it was unceremoniously ousted from the development program. The US was uncomfortable with Turkey operating the F-35 along with S-400, a sophisticated high-altitude interceptor capability designed to take down the latest US and European fighter jets.

The US has been apprehensive that the technology of the fifth-generation stealth fighter doesn’t fall into the wrong hands. It was this fear that drove the US and NATO allies to recover the F-35 that crashed in the Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean.

With Turkey’s homegrown fifth-generation twin-engine fighter jet KAAN making some progress, Turkey can survive exclusion from F-35 fighter jet development. Experts point out that the political U-turn got Turkey what it required to refurbish its aging F-16 fleet – 40 new aircraft and kits to overhaul 79 of its existing fleet of the F-16 fighter jet, along with 900 air-to-air missiles and 800 bombs.

Three primary developments convinced Erdogan to back Sweden’s ascension to NATO. An Indian journalist based in Turkey, Iftikhar Gilani, told the EurAsian Times: “First (of the developments), the Biden administration agreed on Turkey’s request for US $20 billion worth of F-16 fighter jets deal. Several phone calls and meetings between senior Turkish officials and their American counterparts – including the foreign ministers, chief advisors, and spy chiefs – established an understanding of the F-16 request.”

The US tried to dissuade Turkey from purchasing S-400 by offering to sell its Patriot Air Defense System. In the last-ditch effort, it also offered to keep Turkey in its F-35 program if Ankara kept its S-400s de-activated.

But the US attached a string to it. The precondition was that American military officials would inspect the status of S-400s, which Erdogan said violated Turkey’s sovereignty.

The second was the re-opening of negotiations for Turkey’s full-fledged membership of the European Union. Negotiations for full membership started in 2005, soon after Erdogan came to power. They hit a wall in 2018. The first 10-12 years of Erdogan’s reign saw an economic boom driven by global investments. The investors hoped to take advantage of the country becoming part of the EU – a large market.

“But as hopes for Turkey joining the EU faded, these investments started running away. Erdogan hopes that the EU membership will re-invigorate investors’ enthusiasm,” Gilani added. The prime driver for Erdogan’s economic revival plan is the local body elections scheduled in April-May 2024.

Gilani added: “There are no provincial elections in Turkey, so local body elections matter a lot in Turkish politics. The Mayor of Istanbul has the same powers and aura as the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh (a state) in India.”

“So, a lot is at stake. He also needs money to rebuild homes in 11 earthquake-affected areas. Erdogan has been trying to get the country’s EU membership on track for several years. Now, Biden has also extended support for this Turkish endeavor,” Gilani said while talking about how the West wooed Turkey back to its corner.

Erdogan has tied his backing of Sweden’s bid for NATO to his country’s entry into the EU. “First, open the way for Turkey’s membership in the European Union, and then we will open it for Sweden, just as we had opened it for Finland,” Erdogan said in a televised media appearance on Monday before departing for the NATO summit in Lithuania.

Turkey and the EU have had a love-hate relationship. Ankara first applied to enter the European Economic Community, the predecessor of the European Union, in 1987. But Erdogan’s insatiable want for powers put a spanner in his EU’s ambitions. He gave himself more executive powers through a referendum in 2017.

In 2016, the EU depended on Turkey for handling the influx of refugees and gave US $ 6.5 billion to Ankara for rehabilitating the refugees. In 2023 the number of refugees coming to European borders is not that high. But Turkey is still hosting 4 million refugees, giving it a lot of negotiating power when it comes to the EU.

Erdogan also wants Sweden to come through on its deal arrived at in June 2022 that called for cracking down on groups that Turkey considers inimical to its national security, including the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, which Ankara considers the Syrian branch of the PKK.

In addition, Ankara wants Stockholm to extradite suspects it has designated as ‘terrorists’ and lift the arms ban imposed on Turkey.

Sweden has also taken a series of steps to placate Erdogan, such as convicting a Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) supporter, launching investigations against terror funding, and closely working with Turkish security agencies to establish a desk to track activities in Sweden of people linked to the Kurdish armed group.

Also, the Swedish govt distanced itself from the burning incident of the Quran and has held the view that it may bring law to ban the desecration of holy books.

“Sweden has said that it would actively support efforts to re-invigorate Turkey’s EU accession process, including modernizing the EU-Turkey customs union and liberalizing visa application processes,” Gilani added. Turkey has approved Finland’s membership in NATO but has held back its support for Sweden’s bid as a bargaining chip.

Sweden and Finland applied for NATO membership last year, abandoning their policies of military non-alignment following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. New members require approval from all NATO countries, and Finland was given the green light in April.

- Ritu Sharma has written on defense and foreign affairs for over a decade. She holds a Master’s Degree in Conflict Studies and Management of Peace from the University of Erfurt, Germany. Her areas of interest include Asia-Pacific, the South China Sea, and Aviation history.

- She can be reached at ritu.sharma (at) mail.com