Come 2023, there will be as many as eight cabinet ministers from Canada in the Indian Capital, New Delhi, apart from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Is that something surprising for a country led by Trudeau, whose equation with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not been that warm in the past, and for a country where the Trudeau government hesitates to act against the votaries of India’s disintegration in the name of an independent state of Khalistan?

The answer probably lies in Canada’s new “Indo-Pacific strategy,” in which “constructive engagement with India” is an area of priority.

Canada Eyeing Better Ties With India?

As it is, Canada’s foreign minister Mélanie Joly, expected in India in March 2023, spoke to Indian External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar last week.

She will be followed by Canada’s minister of national defense Anita Anand, who happens to be of Indian origin, also in March. As former Indian high commissioner to Ottawa Ajay Bisaria says, “2023 should be the year of a necessary reset in the Indo-Canadian strategic partnership. It should see a stronger geopolitical and geoeconomic alignment.”

Canada’s new Indo-Pacific Strategy seems to reflect such geopolitical and geoeconomic alignments. Terming the Indo-Pacific, to which it also belongs, as “a new horizon of opportunity,” Canada, through this strategy, has identified four regions to focus on – China, India, the North Pacific (Japan and Koreas) and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).

Incidentally, Ottawa acknowledges that “people of Indo-Pacific origin” (it has identified 40 countries) constitute the largest diaspora in Canada. “1 in 5 Canadians have family ties to the region,” and “it is also home to 60% of Canada’s international students”, the strategy stresses.

Canada realizes that as many of its “closest allies, including the United States, the European Union, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, have increased or are considering increasing their presence in the region, guided by their interests and strategies and based on significant investments in diplomacy, in their military presence, in trade promotion, and development assistance,” Ottawa “has a unique contribution to make based on our particular history and relationships in the Indo-Pacific.”

As the Indo-Pacific is rapidly becoming the global center of economic dynamism and strategic challenge, “every issue that matters to Canadians—including our national security, economic prosperity, respect for international law, democratic values, public health, protecting our environment, the rights of women and girls and human rights—will be shaped by the relationships Canada and its allies and partners have with Indo-Pacific countries. Our ability to maintain open skies, open trading systems, and societies, as well as to effectively address climate change, will depend in part on what happens over the next several decades in the Indo-Pacific region,” the strategy points out.

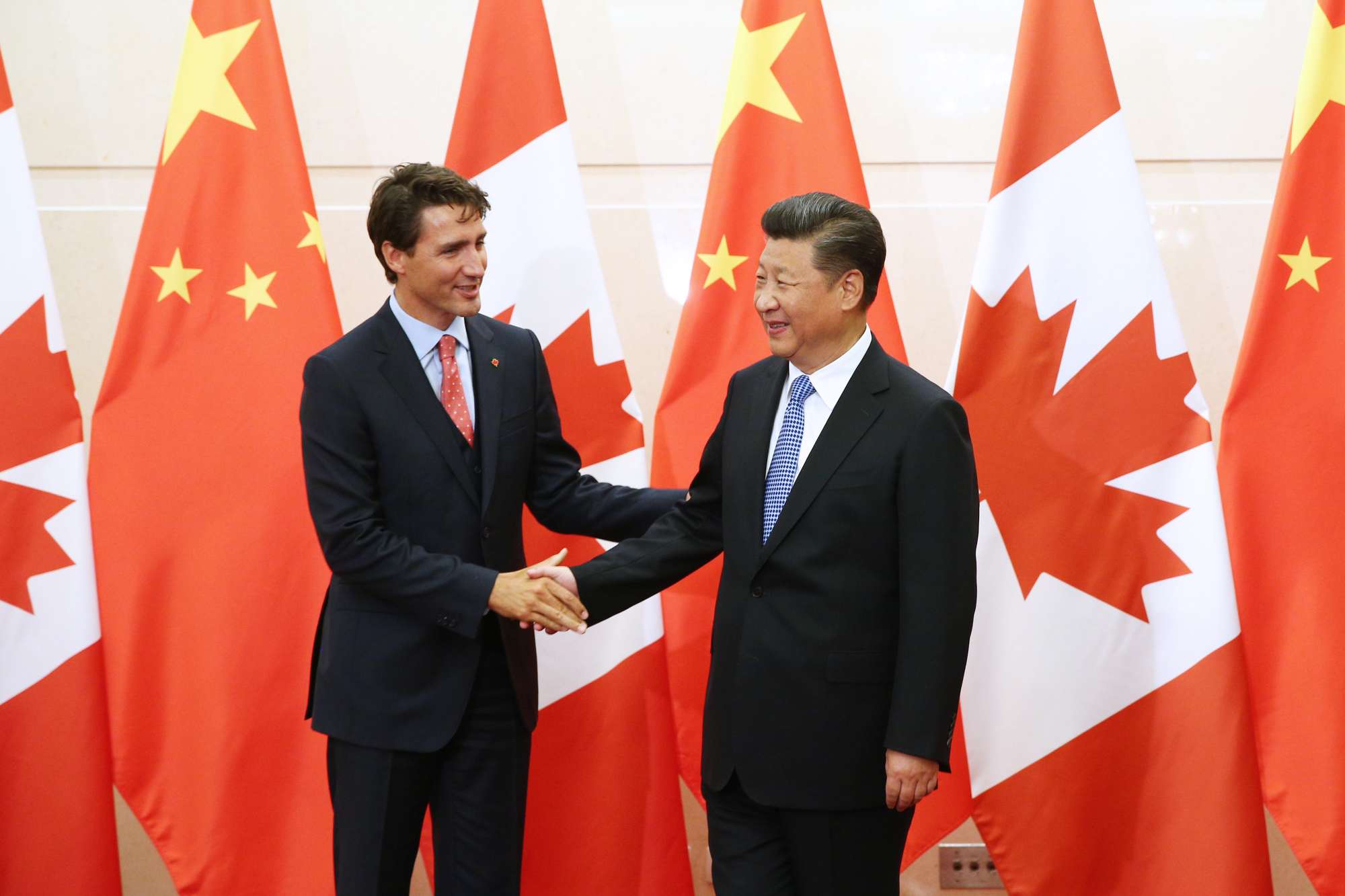

It is to be noted that this strategy of Canada was publicly outlined ten days after China’s Xi Jinping was filmed on November 17, accusing Trudeau of leaking meeting details, days after they held talks at the G20 summit in Bali. And coincidentally, the strategy reflects a change in Canada’s traditional view or position on China, its second-largest trade partner with whom the Trudeau government has pursued close ties.

Canada’s evolving approach to China is critical to the Indo-Pacific Strategy. “China is an increasingly disruptive global power. Key regional actors have complex and deeply intertwined relationships with China. Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy is informed by its clear-eyed understanding of this global China. Canada’s approach aligns with our partners in the region and worldwide.

“China’s rise, enabled by the same international rules and norms that it now increasingly disregards, has had an enormous impact on the Indo-Pacific, and it has ambitions to become the leading power in the region. China is making large-scale investments to establish its economic influence, diplomatic impact, offensive military capabilities, and advanced technologies. China is looking to shape the international order into a more permissive environment for interests and values that increasingly depart from ours,” the strategy says.

It is not that Canada will stop engaging with China. There are areas such as economic progress, renewable energy, cyber security, critical minerals, and climate change where it will deal with Beijing constructively to advance the country’s national interests. But what Omar Allam, managing director, and leader of Deloitte’s global trade and investment practice, considers significant is the strategy’s biggest financial commitment of a half-billion figure given towards military/intelligence cooperation with other allies, along with repeated emphasis that Canada will be vocal about its values to the point of challenging Beijing “in areas of profound disagreement.”

And this is where the importance of India is recognized in the strategy. India’s growing strategic, economic, and demographic significance in the Indo-Pacific makes it a critical partner in Canada’s pursuit of its objectives under this strategy.

It says, “Canada and India have a shared tradition of democracy and pluralism, a joint commitment to a rules-based international system and multilateralism, mutual interest in expanding our commercial relationship and extensive and growing people-to-people connections.

“India’s strategic importance and leadership—both across the region and globally—will only increase as India—the world’s biggest democracy—becomes the most populous country in the world and continues to grow its economy. Canada will seek new opportunities to partner and engage in dialogue in areas of common interest and values, including security and the promotion of democracy, pluralism, and human rights.”

It is to be noted that ever since foreign minister Mélanie Joly enunciated the strategy on November 27, it has been debated by Canadian scholars and analysts, with some saying it was “overdue” and “comprehensive,” whereas others describing it as “inadequate.” Some have also reserved their comments, saying a lot will remain to be seen in the “details on the implementation.”

Goldy Hyder, president and CEO of the Business Council of Canada, thinks that the strategy signifies “good things come to those who wait.” He said the plan was “long overdue.”

China-Canada In The Picture

But there are critics, including leaders from the opposition Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats, who doubt whether the liberals-led government of Trudeau will take on China when “it engages in coercive behavior — economic or otherwise — ignores human rights obligations or undermines our national security interests and those of partners in the region.”

According to Charles Burton, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI), apart from plans to bolster Canada’s military presence by sending frigates to the region, the strategy is unclear about how it will push back against China’s “behaviors that undermine international norms” as it has pledged.

“It is a weak policy, … it’s mostly full of aspirational statements, not about actual action that our government plans to take,” Burton said during a panel discussion held by the MLI on December 14.

Another MLI senior fellow, Stephen Nagy, agrees with Burton, saying, “the Indo-Pacific region may find some elements in Ottawa’s new strategy less relatable or agreeable.”

After all, Canada has committed a $2.3 billion investment in the region over the next five years, which Nagy thinks “is dwarfed by the $3.4 billion assistance that the federal government has pledged for Ukraine.”

The question that Nagy raises is a matter of Canada’s challenges in terms of credibility in the eyes of its allies and friends while pursuing the Indo-Pacific Strategy.

“I think relatability, reliability, and resources are key to understanding how the region sees Canada after the Indo-Pacific Strategy has been released,” Nagy argues. And he seems to have a serious point.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda has been commenting on politics, foreign policy on strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News