The Cold War is often remembered for proxy wars between the two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the US. However, what is often overlooked is the human element in this battle of supremacy.

The nerve-wracking stories of spies and defectors who risked their lives and unwittingly became part of the great game between superpowers.

Many of these defectors were pilots who not only defected to the other side but also flew with the latest fighter jets, providing the other side with crucial insights into these war machines and, in many cases, influencing the other side’s aircraft development programs.

One notable story, and perhaps one of the earliest defections during the Cold War, is the 1953 defection of North Korean pilot No Kum-Sok.

In September 1953, less than two months after the Korean War ended with an armistice, the North Korean pilot flew to a US air base in South Korea with a state-of-the-art Russian fighter jet.

No Kum-Sok flew his cutting-edge Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 from Sunan near Pyongyang to Kimpo Air Base in South Korea on the morning of September 21, 1953. The total flight time from North Korea to landing at Kimbo Air Base in the South was 17 minutes, with the MiG-15 reaching a top speed of 620 MPH (998km/h).

However, this harrowing 17-minute detour from North Korea to South Korea not only earned him a US$100,000 reward (around US$1 million in 2020) but also changed his life and made him famous as one of the first Cold War defectors.

In the US, Flight Lt. No Kum-sok was not content with just being a fighter pilot or living only as a high-profile defector. He reinvented himself as an Engineering student, aerospace engineer, author, and professor at Embry-Riddle.

The High-Profile Defection

At the age of 17, No Kum-sok attended the North Korean Naval Academy and trained in a Yak-18, a light basic trainer. He even trained in Manchuria under Soviet trainers and flew the MiG-15, one of the most advanced Soviet fighter aircraft at the time.

As the war broke out between Communist North Korea, supported by the Soviet Union, and US-supported South Korea, No Kum-Sok, one of the youngest fighter pilots in North Korea, flew more than 100 combat missions. He seemed like any other North Korean fighter pilot, dedicated to the North’s radical Communist ideology.

No one ever suspected that deep inside, he was planning his escape all this while. Barely seven weeks after the three-year-long Korean War (1950-1953) ended in an armistice, Air Force personnel at the US-run Kimpo Air Base near Seoul were surprised to see an unannounced warplane roaring in from the north.

That plane was MiG-15, one of the most advanced Soviet fighter jets at the time. The approaching plane was flashing lights, perhaps signaling that he was not attacking the US-controlled air base.

The Kimpo Air Base had advanced US radars that would have picked up the Soviet-made MiG-15 in an instant and surely challenged the fighter jet, but as luck would have it, the US radars were down for maintenance that day, allowing No Kum-Sok to fly his aircraft to the air base.

When he touched down at Kimpo, his MiG-15 nearly collided with the F-86 Sabre that had just landed at the other end of the runway. According to Blaine Harden, the American Sabre pilot, not believing his eyes, radioed in panic, “It’s goddamn MiG!”

Next, No Kum-sok taxied his MiG-15 in between the F-86 Sabre jets. He exited the jet and started tearing up a picture of the North Korean leader Kim Il-sung.

This was hailed as a major coup as MiG-15 was one of the main adversaries of the F-86s in the 1950-1953 Korean War. No Kum-sok’s defection gave the Americans the first intact model of the MiG-15.

MiG-15 & Korean War: The Jet That Stunned The West

The Soviet Union developed the MiG-15 following World War II, and the fighter jet entered service in 1949. The MiG-15 was the first Soviet fighter equipped with an ejection seat, pressurized cockpit, and swept wing.

The swept wings helped MiG-15 to achieve high transonic speeds. The fighter jet was capable of reaching speeds of 1,042 kilometers per hour (647 mph) at 3,000 meters (9,800 ft).

By 1952, the Soviets provided the MiG-15 (NATO code name “Fagot”) to a number of communist satellite nations, including North Korea.

In 1950, the Soviets began production of a more capable version, the MiG-15bis. The MiG-15bis used a more powerful engine and hydraulically boosted ailerons. During the Korean War, both versions of the MiG-15 operated extensively against US fighter jets and bombers.

With its superior speed and maneuverability, the MiG-15 significantly challenged US air superiority. During the Korean War, the MiG-15 consistently outmatched the newest US fighter jet, the F-86 Sabre, which was lauded as the most advanced fighter of its time.

On November 1, 1950, in the first clash between Soviet and American jets, the MiG-15 shot down at least one US Mustang without suffering any losses. These early successes marked the end of American air supremacy over Korea, as recounted by former Soviet fighter pilot Sergei Kramarenko in his memoir, “Air Combat Over the Eastern Front and Korea.”

One key advantage the MiG-15 held over Western fighters was its ability to reach higher altitudes. With a service ceiling of over 50,000 feet, MiG-15 pilots could easily climb to heights that the F-86 Sabre and other Western aircraft could not reach, providing a haven from enemy fire and a tactical advantage in combat.

The MiG-15 also featured remarkable speed and acceleration, outpacing the F-86 Sabre’s performance. The MiG could achieve a maximum speed of 1,005 km/h, slightly faster than the Sabre’s 972 km/h.

This speed, combined with its climbing rate of 9,200 feet per minute (compared to the F-86’s – 7,200 feet per minute), allowed the MiG-15 to outmaneuver and evade Western jets in dogfights.

The ability to quickly ascend, combined with superior speed, meant that MiG-15 pilots could dictate the terms of engagement, choosing when to engage in combat and when to retreat.

Another crucial aspect of the MiG-15’s dominance was its armament. Unlike the American B-29 bombers, which were equipped with machine guns effective up to 400 meters, the MiG-15 was armed with powerful cannons capable of hitting targets from a distance of 1,000 meters.

The high-explosive bullets fired by the MiG-15 could create holes approximately one square meter in size on enemy aircraft, often causing irreparable damage.

Even if pilots were able to make it back to base after being hit, their aircraft were often too damaged to fly again. In contrast, the MiG-15’s construction and thicker skin allowed it to endure substantial damage and still return to base, giving it a resilience that further contributed to its effectiveness in combat.

The MiG-15’s impact on the Korean War was profound. Retired US Air Force Lieutenant General Charles “Chick” Cleveland remarked that the MiG-15 achieved what German fighters like the Focke-Wulf and Messerschmitt could not during World War II: driving out the US bomber force from the skies.

On one particular day in October 1951, now known as Black Tuesday, Soviet MiGs intercepted and shot down six out of nine B-29 Superfortress bombers. As per Soviet claims, the MiG-15s shot down 1,106 enemy aircraft during the Korean War.

While the US rejected these claims, it was so intrigued by the MiG-15 that it launched ‘Operation Moolah,’ which offered political asylum and a reward of US$100,000 to any pilot who defected with his MiG-15.

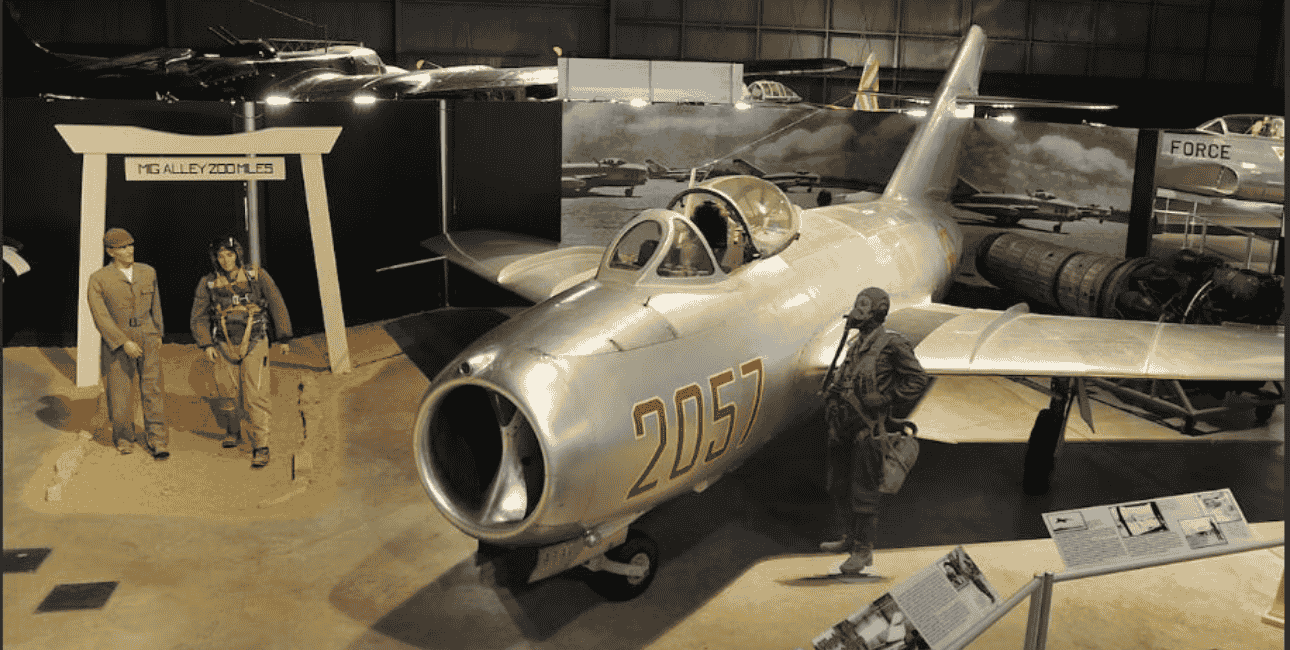

The MiG-15 In US Air Force Museum

According to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, the MiG-15 No Kum-sok flew to Kimpo Air Base and provided “important intelligence data, especially since it was the advanced version of the MiG-15.”

The MiG-15bis was disassembled and airlifted to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in December 1953. It was reassembled and more exhaustively flight-tested.

After considerable flight testing, the U.S. offered to return the airplane to its “rightful owners.” The offer was ignored, and in November 1957, it was transferred to the museum for public exhibition, where it remains to this day.

The North Korean Defector Who Reinvented Himself

When No Kum-sok landed in South Korea with a MiG-15, he claimed he was unaware of Operation Moolah and the US$100,000 reward. He put the money in a trust and used the interest to bring family members to the United States and pursue his education.

He completed his education in Mechanical and Electrical Engineering and became an aeronautical engineer, working for industry giants DuPont, Boeing, General Dynamics, Westinghouse, and General Electric.

Later, he shifted to academia and taught aeronautical science for 17 years at Daytona Beach. Though he was a popular professor with his students, not many of them knew the story of his heroic escape from North Korea with a MiG-15. He died at the age of 90 in January 2023.

His defection and subsequent successful life in the US as a student, engineer, and academic illuminate the many lesser-known human stories from the Cold War era.

- Sumit Ahlawat has over a decade of experience in news media. He has worked with Press Trust of India, Times Now, Zee News, Economic Times, and Microsoft News. He holds a Master’s Degree in International Media and Modern History from The University of Sheffield, UK. He is interested in studying Geopolitics from a historical perspective.

- He can be reached at ahlawat.sumit85 (at) gmail.com