Decades after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world came to the brink of another nuclear showdown between Russia and the United States on January 25, 1995, popularly known as the Black Brant Scare.

Interestingly, the anniversary of the incident coincides with Donald Trump’s recent comments on nuclear arms control talks with Russia and China. Speaking at the Davos Summit, newly-elected US President Donald Trump said: “Tremendous amounts of money are being spent on nuclear, and the destructive capability is something that we don’t even want to talk about today, because you don’t want to hear it.” “We want to see if we can denuclearize, and I think that’s very possible,” he added.

Reacting to President Trump’s comments, the Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said Russia wants to start negotiations as soon as possible—signaling the start of what may be a long-drawn process of eliminating the devastating threat posed by nuclear weapons.

The building momentum on denuclearisation is significant because Russia and the US-led NATO have been embroiled in tensions in the wake of the Ukraine War, with a nuclear threat still looming large over Europe. In September 2024, for instance, Russian President Vladimir Putin warned that Moscow would consider nuclear retaliation if a non-nuclear state supported by a nuclear state launches aggression on Russia.

Amid this increasing nuclear rhetoric from Russia, we recall the ‘Black Brant Scare’ incident — the day when Russia and the US came to the brink of a nuclear showdown thirty years ago.

The Black Brant Scare

The incident occurred several decades after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the time when the two world powers came the closest to a nuclear confrontation during the heat of the Cold War. While the January 25, 1995 incident was not as pivotal as the Cuban Missile Crisis, it was nonetheless a dangerous one.

The Cold War officially ended with the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991. With this, the looming danger of a nuclear war also abated. However, that fear was reignited once again when Russian officers thought a Norwegian rocket launched for observing the aurora borealis was, in fact, a nuclear weapon.

In the wee hours of January 25, 1995, a team of Norwegian and American scientists launched a Black Brant XII four-stage sounding rocket from Norway’s Andoya Rocket Range, a launch location off the northwest coast of the Nordic country. The objective of the launch was to study the northern lights over the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean.

While the scientists had informed Russia and about thirty other states about their high-altitude scientific experiment, the Russian radar technicians somehow never received the information due to a bureaucratic error made by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Unaware of the scientific mission, the Russian Missile Attack Warning System (MAWS) officials stationed at the Olenegorsk Radar Station in northwest Russia (off the northern coast of Norway) detected what they thought was a four-stage missile “launch.” The officers could not instantly identify the missile, but the distance traveled and altitude seemed to match perfectly with the Trident II launched from a US submarine.

The missile appeared to be headed for Moscow. The Russian MAWS had no choice but to consider it as a potential attack and alert the officials in Moscow.

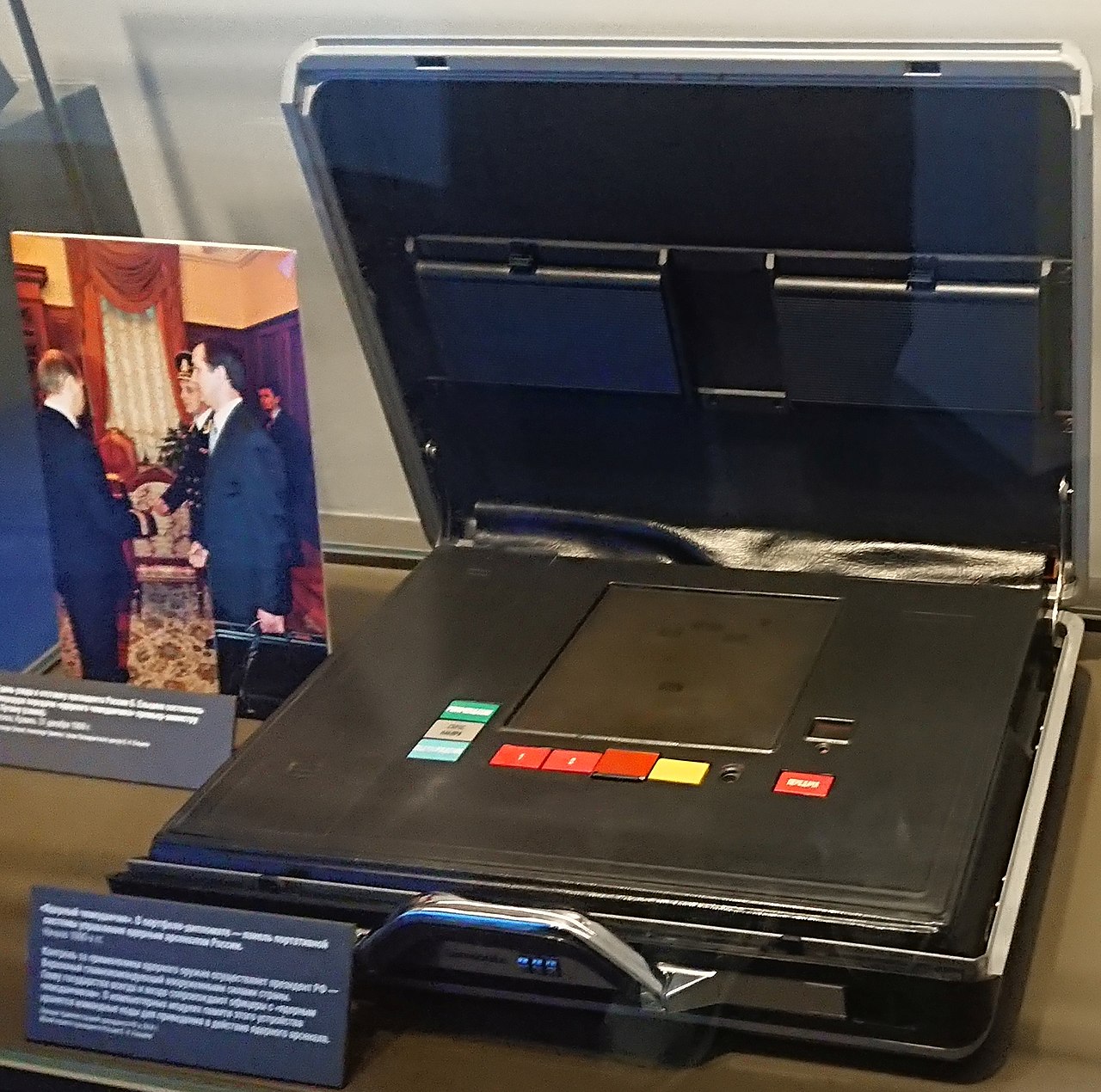

A signal was sent to the nuclear briefcases, called Cheget, that Russian President Boris Yeltsin and other senior defense officials customarily carried at the time. A nuclear briefcase held the launch codes for the country’s missile arsenal that could be used to order a nuclear strike.

As per its typical modus operandi, Russian officials had a deadline: they had to detect an attack, evaluate it, and decide whether to retaliate within ten minutes. Since five minutes had already been spent tracking the “missile’s” trajectory, only five minutes were left for Russia to act.

Russia’s strategic troops were immediately placed on high alert. Procedures from the Cold War era known as “launch on warning” were still in place, which would guarantee mutual destruction in the event of a nuclear attack.

“Despite Yeltsin having the sole legal authority to “press the button,” each man had the technical ability,” reads an excerpt from an article of the Arms Control Centre. Russian submarine commanders were contacted immediately via radio. The Strategic Forces were instructed to prepare for the next instruction, which would have been the launch order.

The Russian commanders waited for the orders. The Russian strategic protocol of the time stated that Russian missiles could be launched before enemy missiles reached Russian territory.

As the rocket separated, radars started to follow each stage. According to reports, one of Yeltsin’s commanders thought these falling parts were more warheads or Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs). However, Yeltsin did not give a launch order.

A few minutes later, the rocket plummeted into the ocean close to Spitsbergen, the Svalbard archipelago’s sole populated island.

The whole thing ended as fast as it had started. The Russian launch was averted, and the forces on high alert were told to stand down.

Yeltsin told the media the following day that he had turned on the cheget. Yeltsin said, “Yesterday, I did use my ‘little black case’ with a button that is always with me for the first time.” “I contacted the Defense Ministry and all the military commanders I needed right away, and we were tracking this missile’s trajectory from start to finish.”

The Russians later learned that the unidentified object was a scientific rocket launched from Norway.

It turned out to be a false alarm and one that risked a nuclear war between the two biggest military powers in the world.

“An officer on duty reported detecting a ballistic missile which started from the Norwegian territory,” recalled MAWS General Anatoly Sokolov.

“If it had been launched on an optimal trajectory, its range would have been extended to 3,500 kilometers, which is the distance to Moscow. The thing is, the start of a civilian missile and a nuclear missile, especially at the initial stage of the flight trajectory, look practically the same.”

While the incident is not remembered as well as other nuclear crises, it did lead to some positive reforms aimed at averting a similar crisis. In the aftermath of the incident, the two sides decided to re-design and re-evaluate the disclosure of missile launches.

- Contact the author at sakshi.tiwari9555 (at) gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News