By Vaishali Basu Sharma

The US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm recently warned about China’s “big-footing” renewable energy technology and supply chains. Global interest in Rare Earth Elements (REEs) for furthering science, technology, and innovation (STI) interventions and emerging geopolitical realities has been rising.

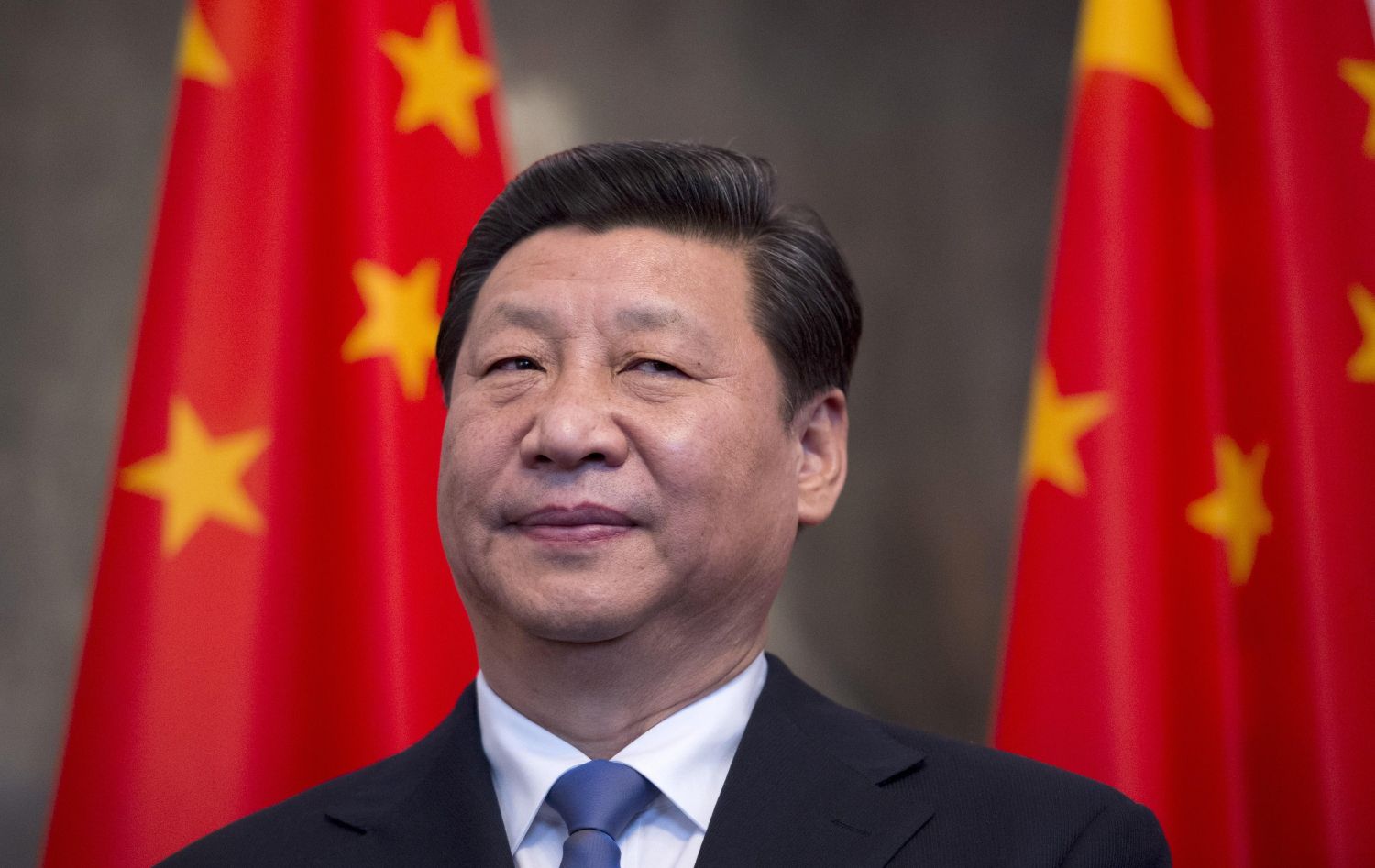

Since China is the world’s largest producer of materials by far and has displayed a willingness to use its export as a punitive geoeconomic tool, the fraught relationship between the countries is directing attention to global supply chain disruption in the rare earth industry.

China’s Monopoly In REEs

In 2021 China produced 168,000 MT of rare earth, and the US imported almost 78% of its rare-earth compounds and metals from China.

Decreasing domestic production means the US’ rare earth import bill has been rising yearly. In 2021 the United States imported rare-earth materials worth $160 million, a significant increase from $109 million in 2020.

While the value chain of REE and their applications have been extensively mapped, Chinese actions of using rare earth supply as an economic lever for geopolitical purposes have lent the subject a certain urgency.

Trade and geopolitical friction between the US and China impact the outlook for rare earth investing. China, the US, Australia, Myanmar, and India have the largest known reserves of REE. And according to some projections, India might even have more rare earth resources than Australia.

Of late, India has been producing less than a ton of rare earth materials domestically and has been selling from its inventory. Over 2021–2030, Australia’s refined rare production is forecast to grow by 69% annually, with possible separation facilities in other countries.

Its Nolans Projects, a mine, and processing facility, north of Alice Springs, is geared to produce almost 5% of global demand for neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr), used in high-power magnets in the initial stages. Australian companies have also indicated keenness to scout for opportunities in critical minerals in India.

Trade and geopolitical friction between the US and China impact the outlook for rare earth investing. Given recent developments, US and Australian collaboration in rare earth mining and production appear to increase.

Australian company Lynas Rare Earths, one the largest in the world aside from the Chinese firms, is in talks with the US Department of Defense to build a multimillion-dollar processing facility in the US.

REEs And Their Many Uses

Because they are not confined to and concentrated in specific areas, their geological exploration and extraction is a daunting task, a set of 17 metallic elements are classified as REEs. They are ‘rare’ because they do not occur anywhere in quantities sufficient to extract cleanly and economically.

Some rare earth minerals are more plentiful in the earth’s crust than copper, and all 17 rare earth minerals are more commonly found in the earth’s crust than silver. Since they occur together, chemically separating them is a highly specialized and expensive endeavor.

Aside from their mysterious occurrence, these closely related metallic elements have nuclear, metallurgical, chemical, catalytic, electrical, magnetic, and optical properties that make them indispensable and non-replaceable in endless modern applications.

Without these REEs, ordinary life as we know it today wouldn’t be possible. In 2018 the US geological survey published a list of 35 minerals and metals critical to progress and national security. Aside from the rare earth elements, the list includes other vital minerals that are essential and irreplaceable for powering most modern technology.

Out of the 35 critical minerals and metals as identified by the US geological survey, China ranked as the number one producer of 16 elements with a monopoly in global production of Yttrium with 99% share, gallium with 94%, magnesium metal with 87% share, tungsten with 82% share, bismuth with 80% share, antimony with 72% share and REE with 80% global production share.

China also produces roughly 60% or more of the world’s graphite, germanium, tellurium, indium, antimony, vanadium, and fluorspar.

The US is a leading producer of only two out of the list of 35 critical minerals, namely beryllium and helium, with no primary production of 22 minerals and five mineral by-products on the critical minerals list.

Every advanced weapon in the US arsenal today, from tomahawk cruise missiles to the F-35 fighter jets, Aegis-equipped destroyers, precision-guided weapons to stealthy drones, and everything in between, is reliant on components made using REE and materials which are almost exclusively made in China.

Each F-35 aircraft jointly produced by 14 allied nations contains 920 pounds of Chinese-origin rare earth elements.

Should More Countries Increase REEs Production?

The world REE market today is controlled by China. Given that the PRC has significantly curbed its export of rare earth materials, it may not be farfetched to imagine that it will shortly impose a total export embargo on these metals.

Disruption in the availability of rare earth will affect the manufacturing of strategic assets, from semiconductors and batteries to defense systems.

With abundant rare earth resources, India was one of the earliest nations to assign due significance to rare earth elements by making organizational arrangements to regulate and develop them.

Unfortunately, over time global developments combined with domestic inertia debilitated any competitive edge India has in rare earth prospecting and mining over other countries.

India aspires to become a world leader in technology like advanced ballistic systems, industrial machinery, semiconductors, electric vehicles, and clean energy systems. Despite having the world’s 5th largest reserve of rare earth elements, India imports most of its rare earth needs from China in finished form.

Several structural problems within the Indian rare earth ecosystem have inhibited the evolution of a spectrum from exploration and mining to producing rare earth materials. It has failed to tap into these resources due to tight regulations and excessive government control.

India has almost 35% of the world’s total Beach sand mineral (BSM) deposits. Unfortunately, for rare earth research in India, the major constituent for BSM is monazite, the mineral from which radioactive thorium is extracted. Because of this connection right from the start, REE research became associated and linked exclusively with the Department of Atomic Energy.

If India can tap into its BSM deposits, it can grab a healthy share of the global rare Earth supply chain. The Modi government has prepared a proposal for opening up two restricted sectors – beach sand mineral and offshore mining for exploration activity by private players.

Critical minerals dominated by a single producing country include niobium from Brazil, Cobalt from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and platinum group metals from South Africa. Chinese producers have successfully negotiated long-term supply agreements within these countries.

In the past, China has demonstrated its ability to directly affect the global supply chain with these elements. In 2020 in response to a US defense deal with Taiwan, China threatened to cut off the supply of rare earth to three American defense manufacturers, including F-35 producer Lockheed Martin.

Recently in a move that is certain to bring further challenges to the global rare earth supply chain China has merged three state entities to establish the China Rare Earth Group Co. Ltd to form a megafirm that will account for almost 62% of its national heavy rare earth supplies.

The equity merger will have pricing power and production efficiency implications, further increasing China’s global competitiveness in the rare earth sector.

Critical minerals and metals affect strategy and geopolitical considerations between nations, and China has precisely grasped and acted on this. It is high time other countries actively pursue the production of REE — beyond academic interest — to contribute meaningfully to its value chain.

- Vaishali Basu Sharma is an analyst of Strategic and Economic Affairs. She has worked as a Consultant with India’s National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS) for nearly a decade. She is now associated with Policy Perspectives Foundation. VIEWS PERSONAL

- You can reach the author at postvaishali (AT) gmail.com