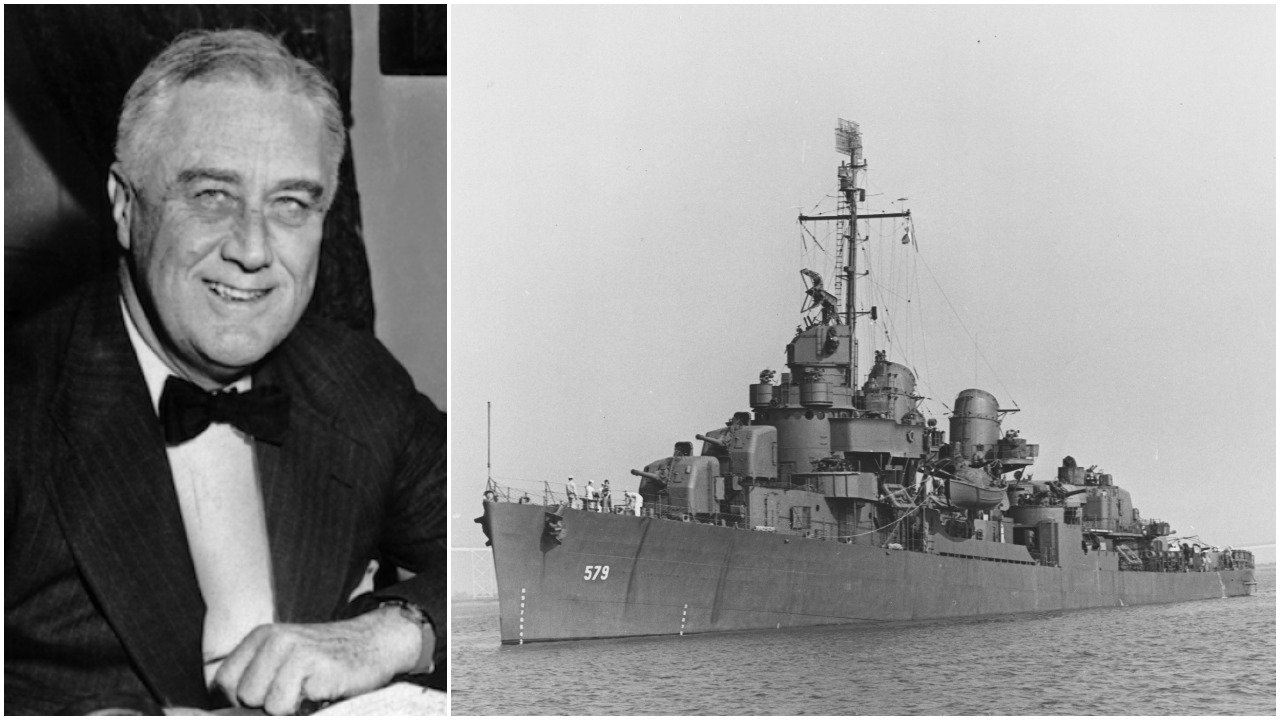

During the Second World War, the US Navy faced countless dangers, but few incidents were as bizarre and consequential as the near-fatal mishap involving President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on November 14, 1943.

On that day, history could have taken a drastic turn, not due to an enemy attack but because of a torpedo fired by an American naval ship—one that could have killed Roosevelt, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and other high-ranking military leaders aboard the USS Iowa.

This close brush with disaster was caused by a torpedo launched from the USS William D. Porter, or “Willie Dee,” as the crew fondly called her.

Had the torpedo hit its target, the political and military consequences would have been catastrophic. The deaths of President Roosevelt and the nation’s top military officials could have disrupted the United States’ war strategy and potentially altered the outcome of the war.

The mistake, though one of the most extraordinary in naval history, resulted from the inexperience and rush that defined the early years of the war for many American sailors.

The USS William D. Porter was one of the hundreds of destroyers hastily constructed by the United States in the early years of the war. Named after a Union Civil War captain, it was part of the Fletcher-class series, a class of warships designed to be fast and agile yet lightly armored.

These “tin cans” were tasked with various duties, from escorting larger warships to protecting convoys and combating submarines, aircraft, and surface warships.

The USS Porter, with its armament—including ten torpedo tubes, depth charge projectors, and radar-guided 5-inch dual-purpose guns—was well-equipped for these roles.

Put into service in July 1943, the USS Porter was staffed by a youthful crew of 125 men, most of whom were fresh from high school, with only a handful of experienced sailors on board.

In the chaotic months of the war, there was little time for extensive training, and the crew’s inexperience was soon tested. Just four months after its commissioning, the USS Porter was assigned to a highly classified mission: protecting President Roosevelt as he traveled to the Tehran Conference aboard the USS Iowa.

The mission was very important, with the world’s future hanging in the balance.

The Secret Voyage

President Franklin D. Roosevelt embarked on a secret mission to French North Africa to meet with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The trip was shrouded in secrecy to protect Roosevelt, with strict orders that no one was to know of his departure until he arrived safely.

Roosevelt’s journey began quietly on November 12, 1943, when he and his entourage, including Secretary of State Cordell Hull and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, slipped out of Washington, D.C., as discreetly as possible.

They boarded the presidential yacht, Potomac, and cruised down the Potomac River, keeping a low profile as they made their way to the Chesapeake Bay, where they would rendezvous with the USS Iowa.

At 45,000 tons, the USS Iowa was a colossal battleship, summoned from its berth in Norfolk, Virginia, to meet Potomac at the bay’s mouth. The Iowa had to offload much of its fuel to avoid running aground in the shallow waters.

The crew on board Iowa had little knowledge of the operation’s purpose until the President’s yacht approached, revealing the high-level significance of their mission.

Grier Sims, a crew member on the Iowa, recalled the moment he realized the importance of their task: “We didn’t know why we were in Chesapeake Bay until the President’s yacht appeared. They had installed a bathtub when we were in Norfolk, and we were all asking what the hell a bathtub is doing on a battleship. Then it made sense when the President came on board.”

Roosevelt was brought on board in his wheelchair, after which the Iowa slipped out to sea under strict orders of radio silence. Joining the battleship were two escort aircraft carriers to provide aerial defense and three destroyers—the USS Cogswell, USS William D. Porter, and USS Young—for additional protection against German submarines lurking in the Atlantic.

Their mission was to safely deliver Roosevelt and his team to Mers-el-Kebir in North Africa, where they would meet Allied leaders for the first major high-level summit of the war.

The fleet traveled at top speed across the Atlantic, with smaller escorting destroyers struggling to keep pace with the powerful Iowa. Most sailors aboard the convoy were unaware of the operation’s full significance, but the high tension among officers hinted that this was no ordinary journey.

The journey would still take eight days at maximum speed, so while they raced across the Atlantic, the crews stayed occupied with training drills and activities.

The Near-Fatal Torpedo Mishap

One of the drills conducted was an anti-aircraft exercise designed to showcase the battleship Iowa’s ability to defend itself. The exercise involved launching several balloons that served as target practice for the ship’s gunners.

While most of the balloons were shot down by the Iowa’s crew, a few of them drifted toward the accompanying destroyers in the convoy, including the William D. Porter, and were similarly destroyed by the destroyer’s gunners.

During these exercises, the Willie Dee showcased its capabilities, particularly its torpedo-launching skills.

The Porter crew intended to impress the President with a simulated torpedo launch at Iowa. Initially, everything went smoothly, with two successful mock launches. However, things quickly spiraled out of control on the third attempt.

At precisely 2:36 PM, a 24-foot-long Mark 15 torpedo was mistakenly launched from the Porter and hurtled toward the Iowa. While torpedoes were notoriously difficult to aim accurately and often unreliable, just one or two successful hits could be disastrous, even for massive warships like battleships and aircraft carriers.

The crew aboard the Porter had no way of knowing whether the torpedo would strike Iowa, but the danger was very real.

The torpedo took just minutes to cover the 6,000 yards between the two ships. Wilfred, the officer aboard the Porter, hesitated to break radio silence, following standard wartime protocols, and decided instead to signal Iowa using a signal lamp.

Unfortunately, the initial messages were garbled twice, making communication unclear. In a moment of desperation, Wilfred finally sent a clearer message: “Lion, lion! Turn right!” (“Lion” being the codename for Iowa).

Iowa’s crew, confused, responded to this cryptic message, prompting the captain of the Porter to clarify: “Torpedo in the water!”

Realizing the immediate danger, Iowa made a sharp turn to port and accelerated to flank speed. At that moment, President Roosevelt, who had been observing the situation from his wheelchair, instructed his Secret Service detail to position him where he could watch the action unfold.

Despite the potential for catastrophe, Roosevelt—ever the statesman—wanted to witness the dramatic event firsthand. Miraculously, at 2:40 PM, the torpedo struck Iowa’s wake and detonated a safe distance away, sparing the battleship from disaster.

Though the ship was unharmed, the close call was enough to provoke serious concern among the fleet’s commanders.

At first, the Navy feared that the torpedo mishap might have been an assassination attempt on Roosevelt. In a show of force, Iowa briefly trained all its guns on the Willie Dee, ready to take action if the incident was deemed deliberate.

Thankfully, the torpedo had failed to cause any damage, and the situation was ultimately attributed to gross incompetence rather than malicious intent.

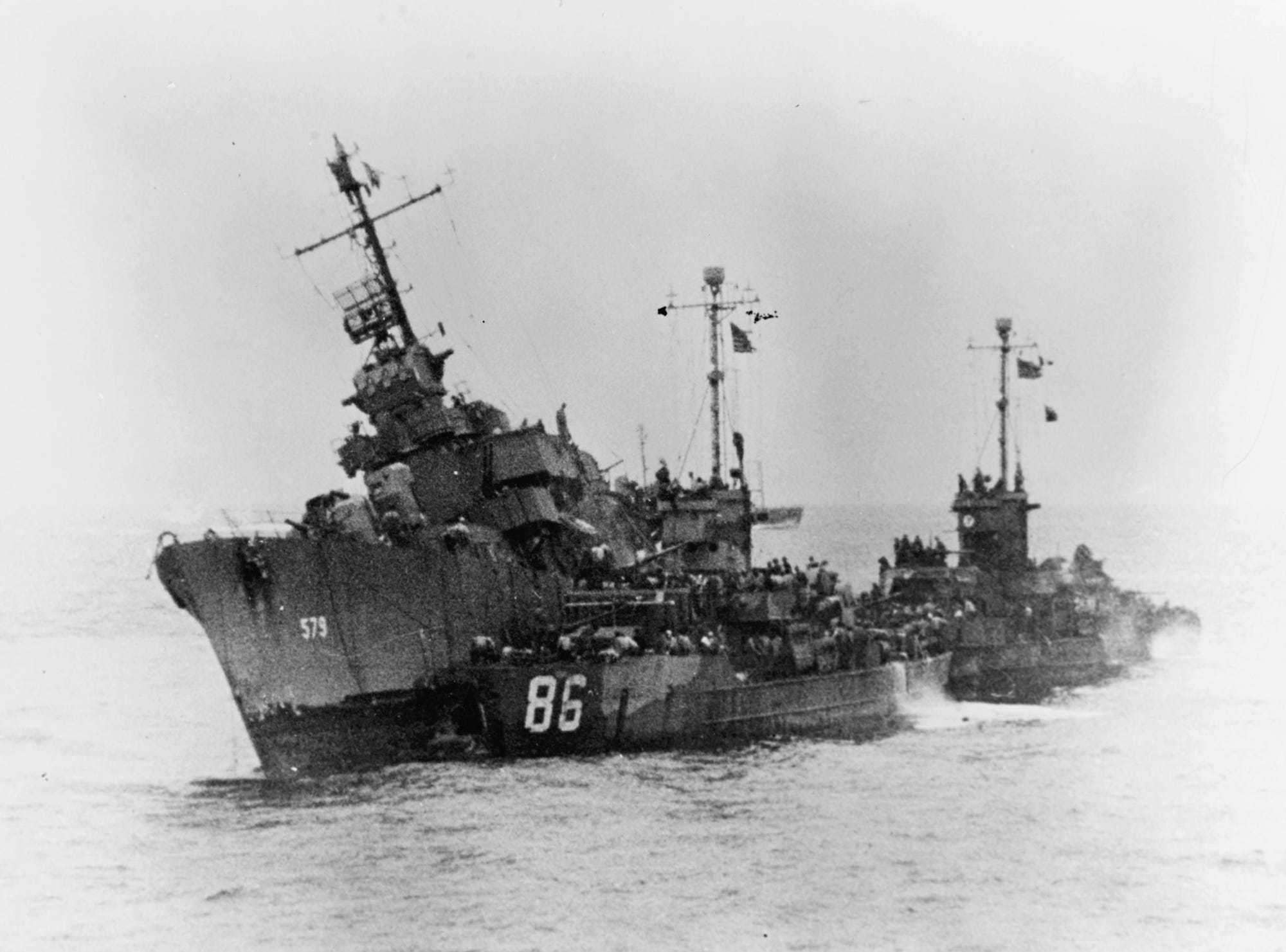

The Porter was immediately ordered to report to Bermuda, where a Navy inquiry would investigate the incident and determine whether it resulted from incompetence or an intentional act of sabotage.

The crew of the Willie Dee was arrested, marking the first time in US Naval history that an entire crew had been detained.

During the inquiry, it was revealed that one of the crew members, Chief Torpedoman’s Mate Lawton C. Dawson, had mistakenly left the primer in the torpedo. He attempted to conceal this error by throwing the evidence overboard during the confusion.

Despite the gravity of the incident, the Navy ultimately decided that the mishap was the result of incompetence rather than any nefarious plot.

Dawson was transferred for a general court-martial. It is reported that he was demoted by one rank to Torpedoman first class. While there was no concrete evidence, several sources suggest he was sentenced to 14 years of hard labor.

However, President Roosevelt intervened, believing the incident to be a mistake, and requested that Dawson not be punished.

Due to wartime censorship, the story remained under wraps, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that the full details of the incident became public. However, word of the near-disaster quickly spread throughout the fleet, becoming a whispered legend.

The Willie Dee would continue to serve in the Pacific Theater until near the end of the war. The ship’s reputation for mishaps followed it, with new crew members humorously chanting, “Don’t shoot, we’re Republicans!” at every new port they entered.

On June 10, 1945, the Willie Dee met its end when a kamikaze pilot narrowly missed crashing directly into the ship. Instead, the wrecked plane exploded underwater beneath the vessel, rocking the ship violently. Remarkably, every member of the crew survived the attack.

Overall, the USS William D. Porter is often referred to as the unluckiest ship in naval history. Its tumultuous service lasted less than two years before its untimely end in June 1945.

Historian Kit Bonner wrote in a 1994 article for The Retired Officer Magazine that the ship’s journey was plagued by a series of misfortunes. It all began with an anchor accident and culminated in a near-disastrous torpedo incident involving the USS Iowa, which was carrying President Roosevelt.

The Porter’s series of misadventures included accidentally releasing a depth charge, losing a sailor overboard, and a drunken crew member firing a 5-inch round while in port, which landed in the “front yard” of the base commandant’s residence. The ship’s troubled journey eventually culminated in its sinking after a kamikaze attack.

- Contact the author at ashishmichel(at)gmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News