For the West, NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) may be the “best ever alliance in the history of mankind,” but for China, it is a “machine that sows the chaos of war.”

On July 26, China accused NATO of continuing to “spread its evil hooks” into the Asia-Pacific region (Beijing refuses to use the term “Indo-Pacific,” now acceptable to the wider world, sans Russia). The Chinese Ministry of National Defense spokesperson Zhang Xiaogang explained how NATO has caused conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Ukraine.

Chinese perception of NATO’s rhetoric as full of “lies, prejudice, incitement, and slander” is understandable in the wake of the adoption of the final communiqué on July 10 at the NATO summit held in Washington. The communiqué identified Beijing as a “decisive enabler of Russia’s war against Ukraine” and posed “systemic challenges to Euro-Atlantic security.”

Will NATO countries change their opinion on China if Beijing, for example, stops supporting Russia in the Ukraine war? It is highly unlikely.

If the NATO communiqué is any indication, China will continue to be a challenge, something that does not necessarily have a linkage with Ukraine. The communiqué has many other complaints. One just has to see its language.

“The PRC continues to pose systemic challenges to Euro-Atlantic security. We have seen sustained malicious cyber and hybrid activities, including disinformation, stemming from the PRC. We call on the PRC to uphold its commitment to act responsibly in cyberspace. We are concerned by developments in the PRC’s space capabilities and activities. We call on the PRC to support international efforts to promote responsible space behavior. The PRC continues to rapidly expand and diversify its nuclear arsenal with more warheads and a larger number of sophisticated delivery systems. We urge the PRC to engage in strategic risk reduction discussions and promote stability through transparency. We remain open to constructive engagement with the PRC, including building reciprocal transparency with the view of safeguarding the Alliance’s security interests. At the same time, we are boosting our shared awareness, enhancing our resilience and preparedness, and protecting against the PRC’s coercive tactics and efforts to divide the Alliance”.

Even otherwise, if one scans through other NATO releases in recent times, it is clear that the alliance is strengthening dialogue and cooperation with its partners in the Indo-Pacific region, known as “IP-4” – Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and New Zealand.

NATO argues that the Indo-Pacific is important for the Alliance, given that developments in that region can directly affect Euro-Atlantic security. Moreover, NATO and its partners in the region share common values and a goal of working together to uphold the rules-based international order.

In fact, even before China and Russia declared their “no-limit partnership” in February 2022 and the subsequent Russian invasion of Ukraine, there were clear, systematic attempts to establish a strong linkage between the Euro-Atlantic (NATO’s principal area of operation) and the Indo-Pacific. Here, the United States, which is as much a Euro-Atlantic as an Indo-Pacific power, had taken a leading role.

Western strategic elites were convinced that a major war initiated by China in the Indo-Pacific would be devastating for the global economy and for the interests of European nations. No wonder why the 2021 EU (European Union) strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific stated that the security of the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait may have a direct impact on European security and prosperity.

It has been argued that European engagement in the Indo-Pacific can contribute to Alliance burden sharing. By helping the United States address its most significant challenge, China, Europe’s NATO partners can help to show that they are valuable allies meaningfully contributing to transatlantic security.

This is all the more imperative as some Americans argue that the United States should pivot away from Europe to allocate more attention and resources to the bigger challenges posed by China and the Indo-Pacific. By helping the United States address the China challenge, Europe’s NATO partners can demonstrate its continued value as an Alliance partner and strengthen US support for continued attention to European priorities, so the argument goes.

The basic point is that all the NATO members acknowledge that the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters are interconnected. At the Madrid Summit in June 2022, NATO Heads of State and Government adopted the NATO 2022 Strategic Concept, the Alliance’s core policy document, which sets NATO’s strategic direction for the coming years.

It talked of “Cooperative Security” as one of its ”three core tasks” along with “deterrence and defense” and “crisis prevention and management.” In this context, the Strategic Concept mentioned for the first time the importance of the Indo-Pacific, noting that “developments in that region can directly affect Euro-Atlantic security.”

NATO has stepped up cooperation with its partners in the Indo-Pacific region in the past few years, including with the first-ever participation of the Heads of State and Government of IP-4 partners in a 2022 NATO summit in Madrid.

During this summit, NATO and the IP-4 partners developed “the Agenda for Tackling Shared Security Challenges” to deepen cooperation in a range of areas, including cyber defense, technology, and countering hybrid threats, as well as maritime security and the security impact of climate change.

In July 2023, the leaders of IP-4 partners also participated in their second NATO summit in Vilnius. Earlier this month, at their third NATO summit in Washington, practical cooperation between Allies and IP-4 partners was further enhanced through the launch of new flagship projects in the areas of support to Ukraine in military healthcare, cyber defense, countering disinformation, and technology such as artificial intelligence.

Apart from these summit engagements, there have also been a series of high-level meetings held between NATO and partners from the Indo-Pacific region over the past years. These include the participation of their foreign ministers in several NATO Foreign Ministerial meetings since 2020, regular North Atlantic Council meetings, and meetings in military format, such as meetings of the NATO Military Committee in Chiefs of Defence session. The last such foreign ministers’ meeting was held in April this year.

Besides, there have been regular bilateral engagements between NATO and important Indo-Pacific countries. On 26 June 2024, NATO hosted military staff talks with Japan at NATO Headquarters in Brussels.

The discussions focused on the ongoing partnership, security challenges, resilience building, and future opportunities for cooperation. The meeting took place under the auspices of the NATO Cooperative Security Division. Similarly, on 14 May 2024, NATO hosted military staff talks with the Republic of Korea at NATO Headquarters.

It may be noted that Japan and Australia have very deep integration into NATO’s military operational structure. As part of the AUKUS agreement, the UK has announced that Australian submariners would receive training aboard Astute-class submarines. Earlier this year, Australia selected the UK’s BAE Systems to build the country’s fleet of nuclear-powered submarines – part of a landmark pact among Canberra, London, and Washington that will also see Australia buy up to five nuclear submarines from the US in the early 2030s.

The NATO partnership is also said to benefit New Zealand through enhanced interoperability, bolstering its armed forces’ capabilities and information exchange, contributing to global security, and upholding the rules-based order.

It is equally important to note that leading NATO countries in Europe, such as France, Germany, and the UK, maintain bilaterally strong security ties, including arms trade, with other leading Indo-Pacific powers, such as India, Singapore, and the Philippines.

Also noteworthy are the facts that these important European powers, all pillars of NATO, have recognized the significance of the Indo-Pacific from their respective security points of view.

The UK had sent a carrier task group to the region not long ago and is reported to do so again next year. It has signed a stationing of forces agreement with Japan.

France and Italy have also sent naval task groups. Defense industrial cooperation is increasing; examples include South Korea’s multi-billion arms sales to Poland and the UK-Japan-Italy Global Combat Air Program.

Naturally, China has reasons to be upset, something that has already been noted. However, China still has its undoubted economic power to ensure that NATO, as an alliance distinct from individual NATO members, will not institutionally get involved in a confrontation with China in the near future.

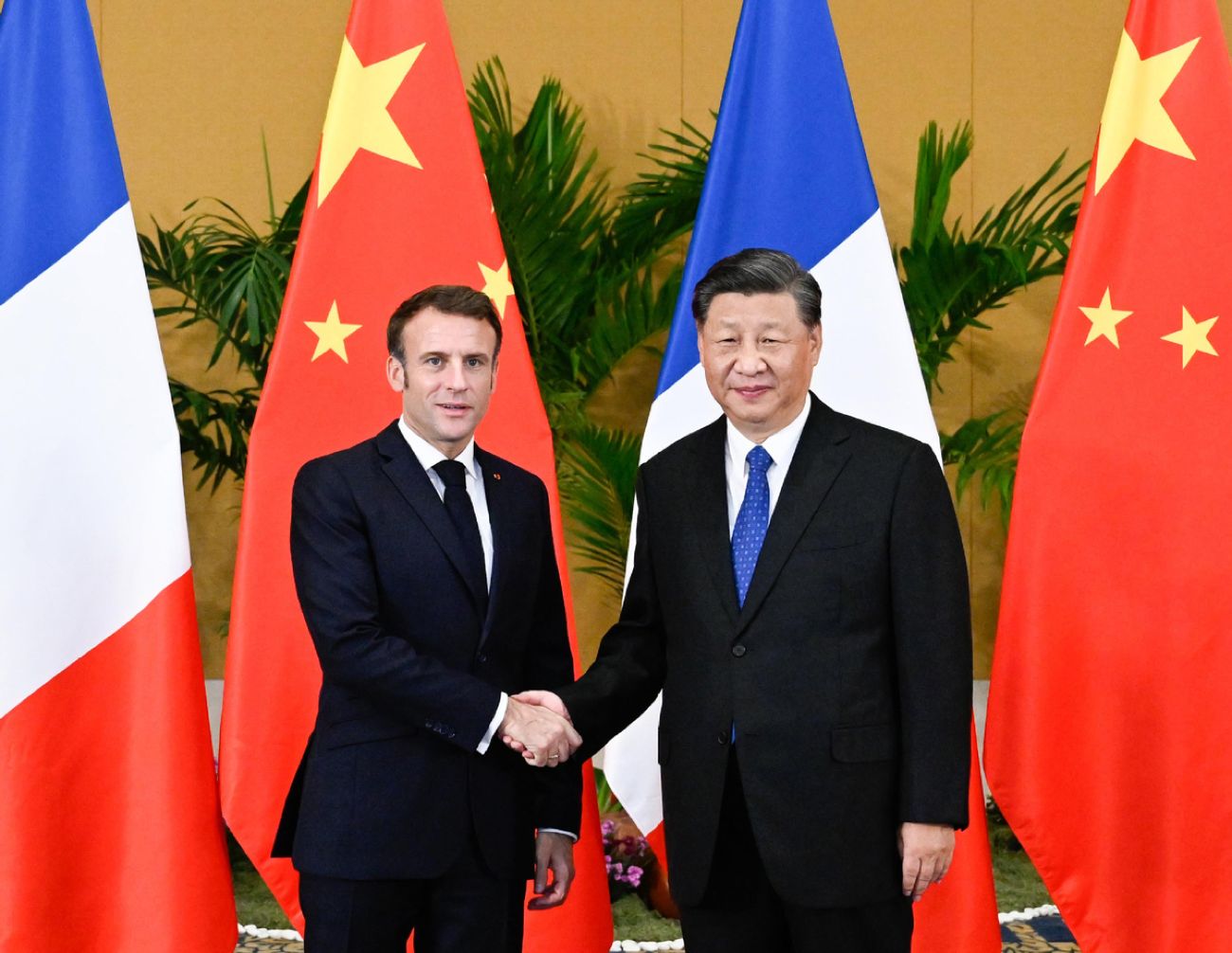

At present, there is no consensus among all 32 NATO members to engage against China beyond a point, with the explicit goal of containing Beijing. France, particularly under President Emmanuel Macron, does not want to burn bridges with China. He has literally vetoed a proposal to open a NATO liaison office in Tokyo.

Germany is witnessing a huge domestic debate on whether it should promote Indo-Pacific security at the cost of €250 billion ($274 billion) trade relationship with China, the country’s largest trading partner, for the last eight years.

Other smaller NATO countries, like Hungary, are strengthening relations with China, which include law enforcement and security cooperation, as well as deeper trade and investment ties.

With these broad divisions among the NATO nations apart, there is also the question of whether NATO has the real hard power, given its primary commitment to Europe’s safety, to expand its remit in the Indo-Pacific to contain Chinese power.

Of course, the United States, NATO’s ultimate leader, will want the alliance to play a bigger role in the Indo-Pacific. But the reality check is that other than demonstrating their symbolic support in the form of more and more joint security drills with the US and other Indo-Pacific powers to emphasize the importance of freedom of navigation and the security of the region’s key choke points, leading European members of NATO may not do much.

However, all this is for the moment. Any Chinese attack on Taiwan could alter the scenario.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda is Chairman of the Editorial Board – EurAsian Times and has been commenting on politics, foreign policy, on strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Professor at Reva University, Bangalore.

- VIEWS PERSONAL OF THE AUTHOR

- ARTICLE REPUBLISHED WITH MORE INFORMATION

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News