With hotly contested maritime disputes with almost all neighboring littorals, China also has land borders with 14 countries. It has settled terrestrial boundaries with all except India and Bhutan.

However, the settlement has been on China-dictated terms. Tajikistan had to yield 1,100 sq km in a settlement in 2011.

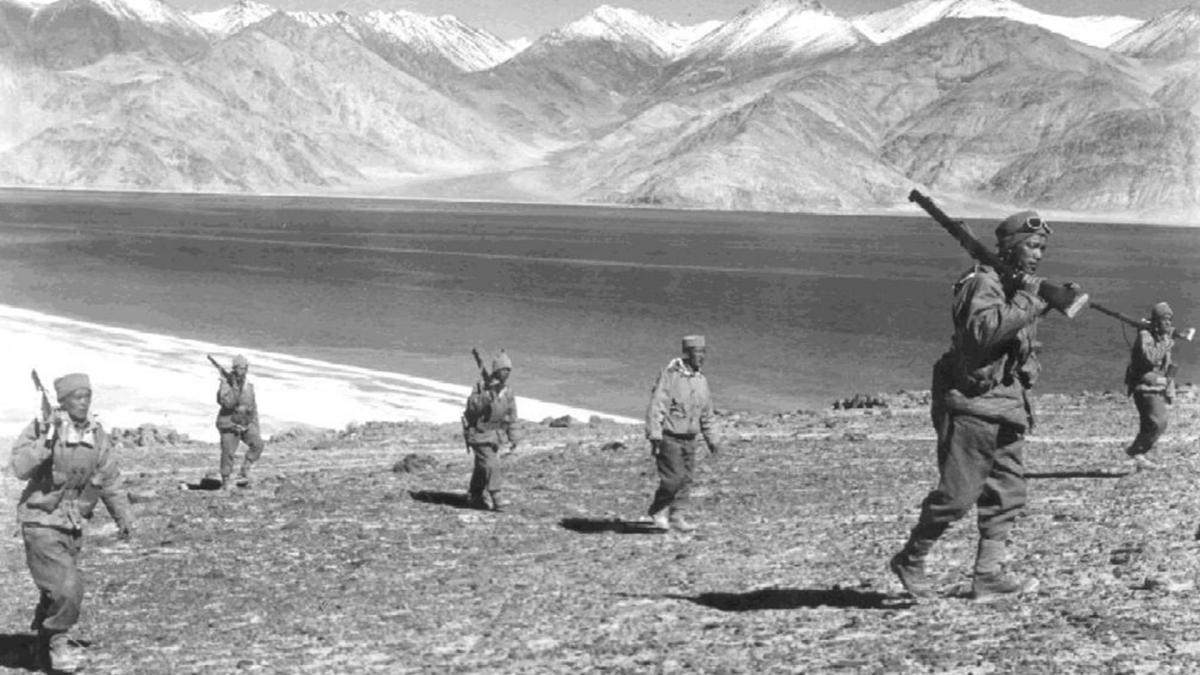

China attacked India and occupied large tracts of territory in Oct-Nov 1962. Yet, inexplicably China unilaterally declared a ceasefire and withdrew 20 kilometers behind its claim lines.

It bears reiteration that China has fought land wars with South Korea, Russia, and Vietnam, besides India.

The undefined border with India is called the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The genesis of the problem can be traced back to the unresolved border between British India and Tibet. China exercised only suzerainty over Tibet, which Beijing later annexed in 1951.

A Brief History Of Clashes & Settlements Between India And China

LAC stretches approximately 3,500 kilometers from Ladakh in the West to Arunachal in the East. After 1962, there was another localized bloody armed clash in 1967 in the Sikkim sector. However, since 1967, there has been no firing on LAC except an isolated, minor accidental shooting in 1975.

In 1986-87, both countries came dangerously close to another clash during a year-long stand-off at Sumdorong Chu in Arunachal. This triggered a series of diplomatic parleys leading to de-escalation, but India had solidified its position around McMahon Line.

This delineation is based on the watershed principle and is generally accepted as the boundary in North East. China’s settled border with Myanmar is based on the very same line.

A set of protocols governed uneasy stability on LAC termed Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) stipulated in treaties starting from 1993 and supplemented by six agreements in 1996, 2003, 2005, 2012, and 2013-14.

The first treaty in 1993 defined the objective as peace and tranquility on the border. Ironically, while the framework was crafted, the border has remained undefined.

India has been pushing for priority to the delineation and definition of the border. On the other hand, China has put it ‘on hold.’

In the interim, trade between both countries has grown, albeit skewed, increasing India’s dependencies. China has been building infrastructure and capability on the border.

It has gained appreciable asymmetry, even in border infrastructure, besides economic and military domains.

Starting from 2013 and with President Xi Jinping, China has initiated the process of salami-slicing to grab strategic territory and alter the reality of LAC. It began with Depsang in Ladakh in 2013. In 2014, there was another stand-off in Chushul in Ladakh even when President Xi was visiting India.

Chinese transgressions in Ladakh are to solidify control over Aksai Chin. These provide depth to strategic communication like G-219, linking Tibet with Xinjiang, which connects with CPEC.

The scene shifted to Doklam in Sikkim in 2017 with another stand-off at a tri-junction between two countries with Bhutan. China taking advantage of COVID-19 and, in the garb of an unnotified war game, orchestrated a series of grab actions starting in May 2021.

The most serious was at Galwan, where India lost 20 soldiers, including one Colonel. China accepted losing four, including officers. Both sides didn’t fire, but PLA used spiked clubs and tasers like barbaric contraptions.

The Yangtze Incident

The Yangtze incident on December 9 was yet another reminder that PLA’s diabolic game of altering realities on LAC continues unabated. The choice of location and timing of the next round of salami-slicing adds a psychological dimension to retaining control of the escalation matrix.

Every such round is followed by some parleys, with meaningless terms like stability, peace, and tranquility. The recent statement of Chinese FM Wang Yi has evoked much skepticism and little optimism. For soldiers on the ground, it translates to enhanced deployment and surveillance.

The Yangtze is the tactical prong, combined with the theological one-Tawang, defining the template in evolving strategic game to further the Chinese claim on Arunachal, described by the Chinese as Zang Nan (Southern Tibet). Yangtze has great spiritual significance due to its proximity to Chumi-Gyatse, a holy waterfall.

Chinese checkers has taken another twist from earlier Chinese articulated move, first in the 50s and repeated till the 80s of ‘swap-settlement’ – entailing control of Aksai Chin for China in lieu of Arunachal for India.

China has gained in asymmetry, and its revanchist cravings have multiplied. Having achieved its claims in Ladakh, grabbing is now unfolding in Arunachal. China seems no longer interested in any mutual accommodation.

The loss of the Yangtze in 1987-88 still rankles China as it is the potential launch pad to reclaim Tawang, the birthplace of Dalai Lama.

Chinese have regularly staked their claim, but it was different this time. The massive strength of the raiding party of 300 plus in peak winter (mid-Dec) at 3.00 am, indicates detailed planning and clearance at the highest level.

It is to the credit of the Indian Army that they were vigilant and pushed back riot-clad PLA marauders equipped with spiked sticks, tasers, and barbaric contraptions.

As analysts lapse into the usual frustrating analysis of the why and how of incidents, the only certainty is that it will likely happen again. It is appropriate to recall that we have not found conclusive answers to the original question on the 1962 War.

Why did PLA go back if it wanted areas like Galwan and Tawang so badly? Analysis has to be based on a reality check on how Beijing perceives India in zhengzhi-junshi-zhang (politico-military war).

The recent much-acclaimed report of former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale sums it up in four inferences. First, as an unequal and unreliable neighbor unworthy of any stand-alone status or consideration.

Second, relevant only in hyphenated mode tagged with great powers in strategic trinity- USA, USSR, and China. The third clear expectation is that India should first understand Chinese objectives.

To put it bluntly, India should play along. Fourth, China can afford to deal with India in episodic tactical mode within its own long-term strategy. Consequently, China’s petty ‘zero-sum’ approach to deter India in the Indian Ocean and neighborhood continues unabated.

The Way Ahead For India

The natural result is how India is dealing with China. It may sound incredulous, but seemingly, without a coherent strategy, India is responding in a reactive mode constrained by existing asymmetry.

It is a strange mix of optimism and denial amongst decision makers (diplomats and experts) searching for the elusive peace and tranquility, even when the ‘wolf-warrior’ remains unrelenting.

There have even been instances of conceding the benefit of the doubt and accepting explanations of local Commanders going rogue. But the same so-called rogue is now in the apex hierarchy in CMC.

Even worse is a sense of bravado seen amongst social-media warriors giving clarion calls to liberate Aksai Chin. As per a reliable opinion poll by an international think tank, 60% of Indians believe that they can simply put it across to the Chinese.

Galwan is the defining marker, with Indians jettisoning the residual trust in the Chinese. China may not have realized the long-term damage it has inflicted on itself.

The post-1962 generation of Millennial and Cross Millennials Indians impressed by Chinese economic progress had no recollection of the 1962 defeat and wanted to collaborate. The dominant narrative is of Chinese deceit and bullying, even when the pandemic was raging.

Chinese game plan is based on a gross underestimation of Indian capability, appetite, and even willpower to impose costs on China.

While this may be true in some measure in the politico-bureaucratic hierarchy, it will be fatal to miss out on the resolve at the tactical level. Even at a higher level, Operation Snow-Leopard to occupy the Kailash range by the Indian Army in August 2022 indicated audacious resolve and political will.

China has destroyed the edifice of CBMs and border management protocols with Galwan, Yangtze, spiked clubs, and tasers. While Indian troops have shown remarkable restraint, incidents can spin out of control under provocation, leading to serious escalation.

Buffer zones with PLA in grab mode will not help, as probing is part of defensive surveillance. Such surveillance is axiomatic when xiao-kangs (militarized border villages are being created) by PLA near LAC.

Two nuclear nations wrestling across the undefined lines with stone age weapons should spur leaders and diplomats on both sides to resolve at least interim border management protocols.

China seems to follow an old Chinese maxim, ‘one mountain cannot contain two tigers.’ It is time China accepts the reality of India being a credible neighbor with legitimate aspirations and heeds to the old maxim, ‘good fences make good neighbors.’

The Himalayan mountains are enormous, and two Tigers can find accommodation with maturity and wisdom.

- Lt Gen KJ Singh, PVSM AVSM & Bar (Veteran), is a former Western Army Commander & State Information Commissioner. Views Personal

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News