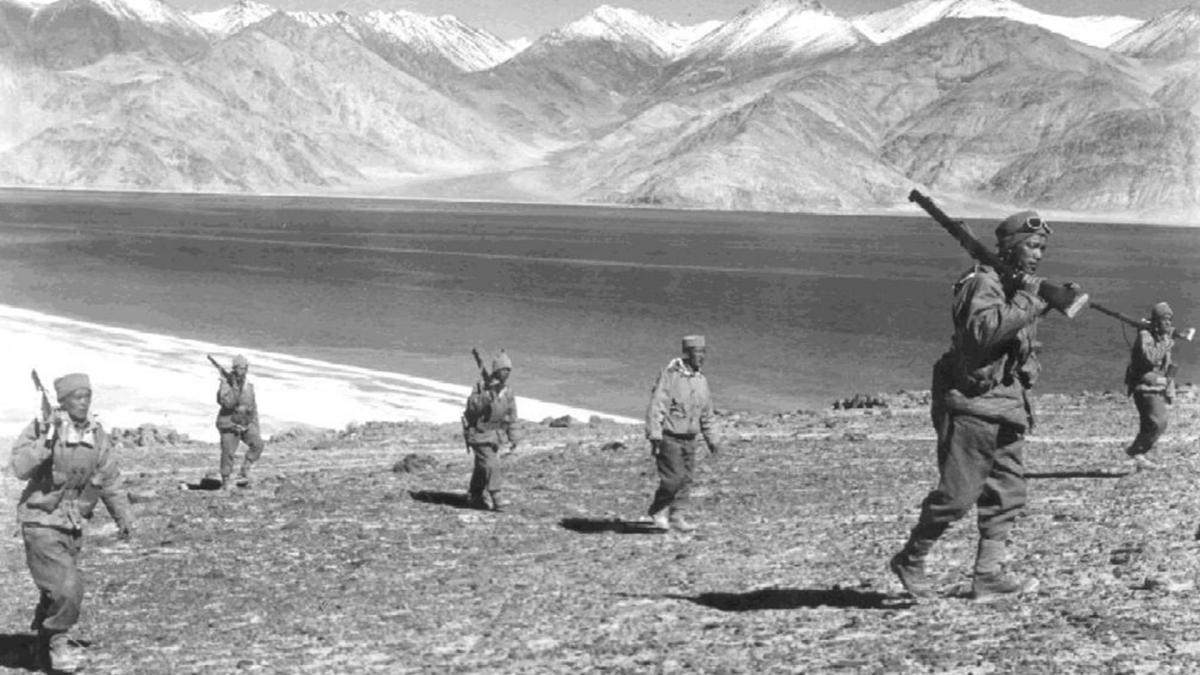

Ever since the skirmish in June 2020 between the Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan valley of India’s Ladakh region, retired Indian diplomats and military officers, as well as civilian-military analysts, have authored several books on the India- China border dispute and the 1962-war between the two.

The latest in the series happens to be one by Sandeep Mukherjee, whose book “The 1962 India-China War: What They Don’t Want You to Know” has been discussed by the EurAsian Times.

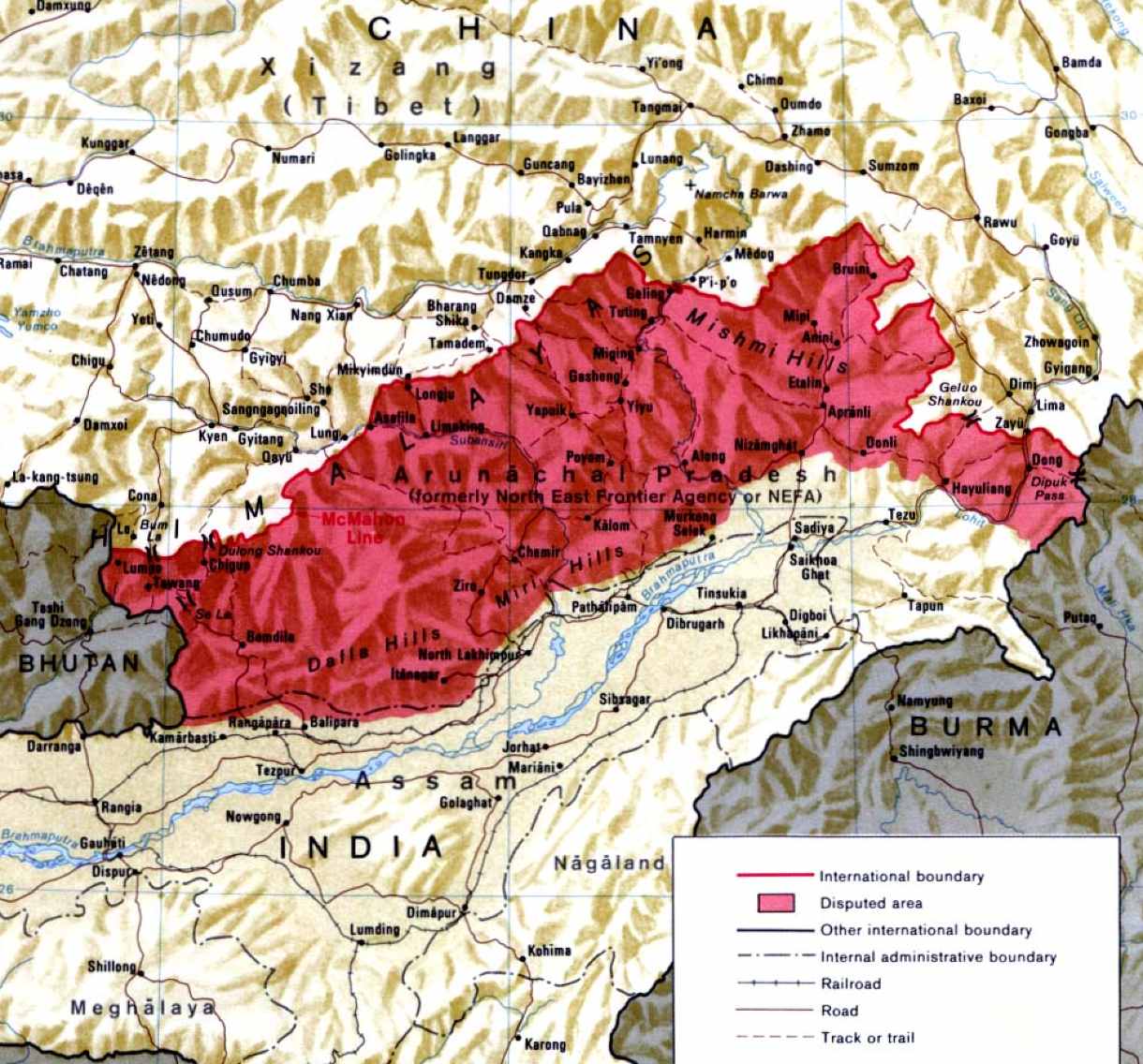

Even otherwise, discussions on the 1962 war continue to be in the headlines (it dominated even the proceedings in the recent Parliamentary session in India), given the border clash in the Tawang sector of Arunachal Pradesh on December 9.

Mukherjee’s book refers to parts of the “yet-to-be-declassified” Henderson Brooks Report (HBR), the official history of the war by India’s Ministry of Defense (MoD). But then the main points of this report are otherwise well-known.

Australian journalist Neville Maxwell posted in his blog on March 17, 2014, the classified Henderson Brooks 1962 war report.

He released a 126-page section of the report’s first volume, which includes an operational review of India’s failure in the war with China in 1962. Predictably, the Indian government reacted. Though it is not being admitted officially, it is widely shared that no one in India can now access Maxwell’s blog because of the government’s intervention.

I am told that Maxwell’s website is also inaccessible in Britain. But then, no government can suppress information, however powerful it may be, in this age of the information revolution.

Alert scholars and media persons downloaded the leaked report from other websites that had already downloaded it from Maxwell’s blog before it became inaccessible.

My friend, the late Bharat Verma, and I downloaded the Henderson report in our respective publications that we edited. I am not sure whether this “classified report” is still available easily on the web, but for the readers of the EurAsian Times, here it is.

It may be noted here that the report is the “Henderson Brooks-Bhagat report,” also referred to as the Henderson Brooks report.

It is an analysis (Operations Review) of the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Its authors were officers of the Indian armed forces— Lieutenant-General Henderson Brooks and Brigadier PS Bhagat. They were asked by the then Defense Minister YB Chavan through the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) JN Chaudhury to prepare a report on what went wrong in 1962. The COAS presented its report to Chavan on July 2, 1963.

It contained a great deal of information on the operational nature, formations, and deployment of the Indian Army.

Reluctance To Publish The Report

Maxwell has released a section that includes four chapters, but not the secret second volume, highlighting sensitive correspondence on decision-making in the lead-up to the war.

The chapters, according to him, show that there were many assessments from commanders on the ground to Delhi, which, if considered by the Nehru government, would have led to a revision of “the Forward Policy” and averted the debacle.

Maxwell, who authored the highly controversial book “India’s China War,” based on the report, had explained his decision to release the report, saying he believed he was “complicit in a continuing cover-up” by keeping the report to himself. “Those who gave me access to the Henderson Brooks Report when I was researching my study of the Sino-Indian border dispute laid down no conditions as to how I should use it. That they would remain anonymous went without saying, an implicit condition.

I will always observe; otherwise, how the material was used was left to my judgment. I decided that while I would quote freely from the report, thus revealing that I had had access to it (and indeed had a copy), I would neither proclaim nor deny that fact, and I assumed that the gist of the report having been published in 1970 in the detailed account of the Army’s debacle given in my India’s China War, the Indian government would release it after a decent interval.

“The passing years showed that assumption to have been mistaken and left me in a quandary. I did not have to rely on memory to tell the falsity of the government’s assertion that keeping the Report secret was necessary for national security. I had taken a copy, and the text nowhere touches on issues that could have current strategic or tactical relevance. The reasons for the long-term withholding of the report must be political, partisan, and familial. While I kept the report to myself, I was complicit in a continuing cover-up.

“My first attempt to put the report itself on the public record was indirect and low-key: after I retired from the University, I donated my copy to Oxford’s Bodleian Library, where, I thought, it could be studied in a setting of scholarly calm. The Library initially welcomed it as a valuable contribution in that ‘grey area’ between actions and printed books, in which I had given them material previously.

But after some months, the librarian to whom I had entrusted it warned me that, under a new regulation, before the report was put on the shelves and opened to the public, it would have to be cleared by the British government with the government which might be adversely interested! Shocked by that admission of a secret censorship process to which the Bodleian had supinely acceded, I protested to the head Librarian, then an American, but received no response.

Fortunately, I was able to retrieve my donation before the Indian High Commission in London was alerted of the Bodleian’s procedures and was perhaps given the report.

“In 1962, noting that all attempts in India to make the government release the report had failed, I decided on a more direct approach and made the text available to the editors of three of India’s leading publications, asking that they observe the usual journalistic practice of keeping their source to themselves. (I thought that would be clear enough to those who had long studied the border dispute and saw no need to depart from my long-standing ‘no comment’ position) To my surprise, the concerned editors decided not to publish.

They explained that, while ‘there is no question that the report should be made public,’ if it were leaked rather than released officially, the result would be a hubbub over national security, with most attention focused on the leak itself, and little or no productive analysis of the text. The opposition parties would savage the government for laxity in allowing the report to get out, and the government would rage upon those who had published it.

“Although surprised by this reaction, unusual in the age of Wikileaks, I could not argue with their reasoning. Later I gave the text to a fourth editor and offered it to a fifth, with the same nil result. So my dilemma continued – although with the albatross hung, so to speak, on Indian necks as well as my own. As I see it now, I have no option but to put the report on the internet rather than leave the dilemma to my heirs. So here is the text (there are two lacunae, accidental in the copying process).”

It may be noted here that Maxwell, who as a journalist was based in India at the time of the 1962 war, did not display in his book the impartiality required of a scholar. His was a biased account, admiring China and blaming India for the war, something that many scholars have challenged.

Be that as it may, returning to the Henderson Brooks report, most of its crucial conclusions have been an open secret for years. Thus it is shocking why the Government of India continues to keep it classified.

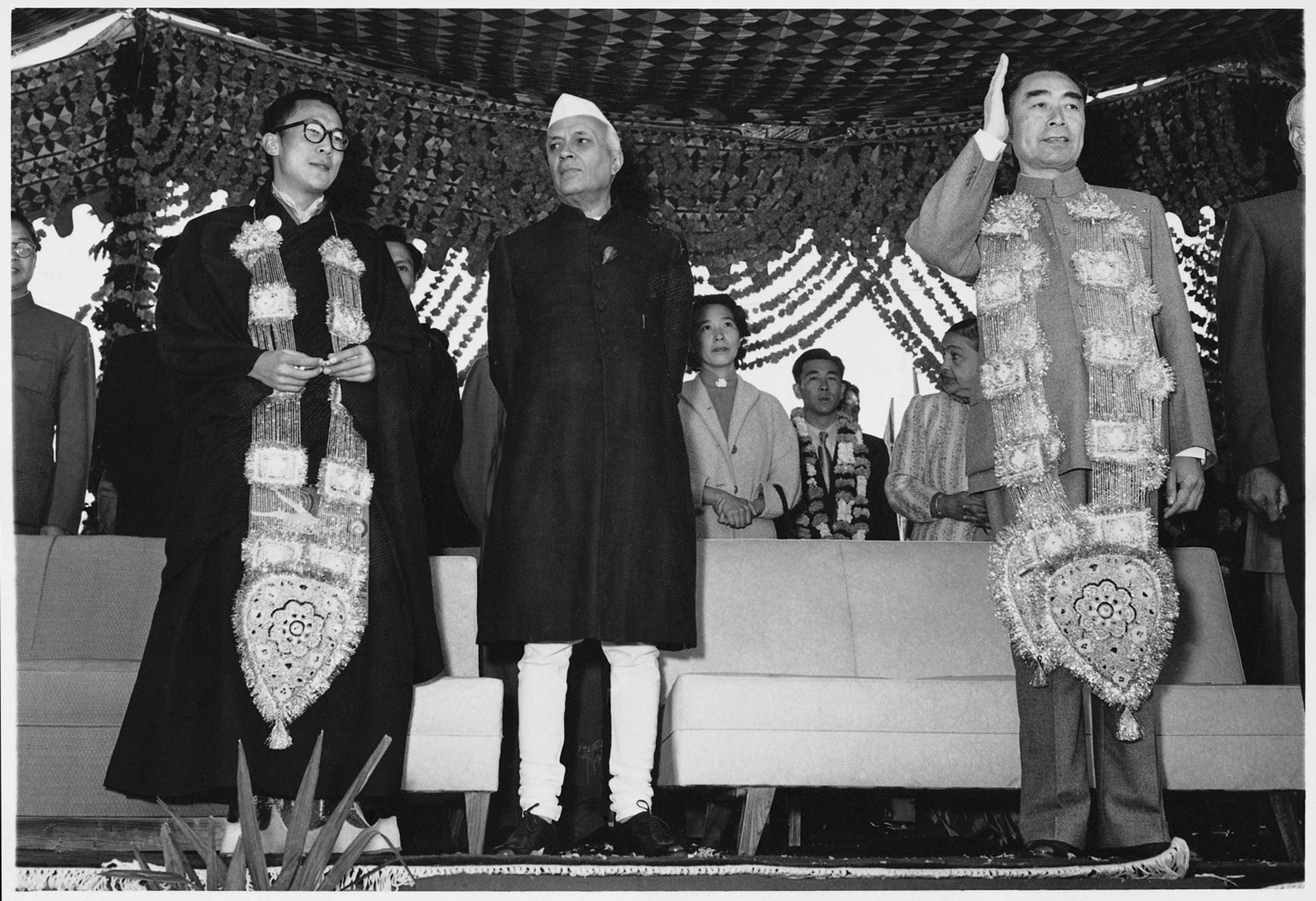

Is it because of our blind reverence for Jawaharlal Nehru? Claude Arpi, a leading scholar on China, thinks so. Warfare has witnessed many a revolution between 1962 and now. So to argue that the report cannot be released officially because of what the Indian government says, “the contents are not only extremely sensitive but are of current operational value,” is not convincing.

On the other hand, the release of the report after 25 to 30 years, as is the practice in many democratic countries to declassify secret official records, could have led to a healthy debate, igniting open and honest scholarly interactions over what led to the border dispute and war and what lessons should be learned to avoid future wars.

In any case, even some official volumes on the 1962 War, brought out by the “History Division” of the Ministry of Defense (MoD), such as Dr. PB Sinha and Col. A Athale authored and SN Prasad edited History of the Conflict with China, 1962, have pointed out how the debacle was due to the absence of institutionalized support for decision-making at the national level.

“Well-established and well-respected agencies providing politico-military linkages were not just there. It was personality-oriented decision-making in the vital areas of national security. That is how Krishna Menon, the Defense Minister, and BN Mullik, the Intelligence Bureau Chief, acquired near total control over the national defense policy and even the disposition of troops in forward areas”, wrote SN Prasad.

One of the principal reasons for the 1962 debacle was that before 1959, none in the then-Indian ruling establishment found any fault with Communist China, mesmerized as they were by the philosophy of Communism and Mao’s brand of Communist practices.

In the Communist style, Krishna Menon wanted a committed, or at least pliant, band of army officers in influential positions to carry out the ideas of the political establishment. That explained why there was a monumental failure of Indian intelligence to assess that China was planning a major attack on the country.

What Lead To The Debacle?

According to the 1992 Ministry of Defense’s Official History, Military Intelligence’s assessment in 1959 was that a “major incursion” by the Chinese was unlikely, given the fact that at that time, India’s pace of industrialization was much better than that of China and that Chinese military was not capable enough “to sustain any major drive across the great land barrier.”

The assumption of Chinese in-action in the event of the crisis was also firmly supported by the then Intelligence Bureau Director BN Mullick, who, many argue, was incompetent for the job, which he got for his proximity to Krishna Menon.

The IB totally identified itself with the view emanating from the South Block bureaucracy (Ministries of Defense and External Affairs) that a limited and high-intensity war with China was “structurally impossible” in a nuclearised bipolar system; because any misadventure by China would lead to global nuclear escalation, a specter that would deter a conflict on the Himalayan border.

Similarly, Defense Minister Krishna Menon repeatedly ignored the pleas of the Army for funds to improve the manpower and weapon systems. For instance, the aforesaid official version behind the 1962 debacle states: “In the years 1959-1960, Lt General SP Thorat, GOC-in-C Eastern Command, had made an appreciation about the magnitude of the Chinese threat to Indian borders in the Eastern Sector and had made projections about his requirements to meet that threat. But the Army HQ and the Defense Minister paid little heed to Gen Thorat’s appreciation. It was not even brought to the notice of the Prime Minister.”

Experts have argued that in 1962, “the Indian Army of 280,000 was short by 60,000 files, 700 anti-tank guns, 5,000 radio field sets, thousands of miles of field cable, 36,000 wireless batteries, 10,000 one-ton trucks, and 10,000 three-ton trucks!

Two regiments of tanks were not operational due to a lack of spares. Indian troops were using .303 rifles which had seen action even before World War I (not II). In contrast, Chinese troops were equipped with machine guns/heavy mortars/automatic rifles.”

Worse, Menon, to a greater extent, and Nehru, to a lesser degree, politicized the then Army hierarchy. General PN Thapar, the then Army Chief, was a great acolyte of Menon and simply rejected every request for better arms and strategies from below. Officers with sound military advice were replaced with submissive ones who carried out the orders.

For instance, the newly formed IV Corps command was given to Lieutenant General BM Kaul, who had never commanded an active fighting outfit! His military strategies were highly flawed. So much so that the official history blamed Kaul for frequently ignoring the chain of command.

The report accused him of approaching the Chief of Army Staff, bypassing the GOC-in-C, and giving orders directly to junior officers, bypassing a chain of middle officers. The politicization of the Army was a key factor behind the 1962 debacle.

Viewed thus, there is no reason why the Henderson report remains classified officially as it has become an open secret. The report in no way will affect India’s border negotiations with China. On the contrary, it will help India better prepare against any untoward eventuality.

- Author and veteran journalist Prakash Nanda has been commenting on politics, foreign policy on strategic affairs for nearly three decades. A former National Fellow of the Indian Council for Historical Research and recipient of the Seoul Peace Prize Scholarship, he is also a Distinguished Fellow at the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

- CONTACT: prakash.nanda (at) hotmail.com

- Follow EurAsian Times on Google News