India and Pakistan have been engaged in a bitter feud over Kashmir since 1947. Pakistan calls Kashmir its jugular vein, while India states the region as an integral part. What makes Jammu and Kashmir so important are its vast natural resources i.e. water, for which both countries are immensely dependent.

China Creating Military Infrastructure in Pakistan-Controlled-Kashmir via CPEC Project: Activists

As rivers have started to run dry in both India and Pakistan, water emanating from Kashmir has the potential to become a major flashpoint between the two nuclear-armed neighbours.

In Pakistan, women and children walk miles every day to scout for water even in the nations financial capital, Karachi. The scenario gets even terrifying in other smaller towns and cities of Pakistan. On the other hand in India, about 75% of people don’t have access to clean drinking water at home while around 70% of the country’s water is contaminated, according to various reports.

The latest dispute between India and Pakistan is over hydroelectric projects which India is building along the Chenab River that Islamabad claims violate the Indus Water Treaty. Indian PM Narendra Modi — who faces elections in the next few months — has vowed to proceed with construction, and it remains unclear how the impasse will be resolved. For now, India has allowed Pakistan auditors to visit the site to assure that the treaty is not being violated.

“Tensions over water will unquestionably propel and put the Indus Waters Treaty to its greatest test. “The prospect of two nuclear-armed rivals becoming embroiled in escalating tensions over water is disturbing and poses severe implications for security in South Asia, according to experts.

For now, relations between India and Pakistan seem to be comparatively calm and even looking more positive. Imran Khan’s government has attempted to mend relations with India, but New Delhi has been circumspect and unwilling to negotiate unless terror activities are not completely halted.

Still, all sides see the long-term risks of conflict over water: Khan himself is attempting to raise $17 billion via the world’s largest crowd-fund for the construction of two large dams, one of which would be built in the disputed territory of Kashmir. In a region that’s home to about a quarter of the world’s population, failure to manage water shortages could be catastrophic.

“Any future war that happens will be on these issues,” Major General Asif Ghafoor, Pakistan’s military spokesman, told reporters last year, referring to water issues. “We need to give it a lot of attention.”

The most serious threat to the water agreement of late followed a terrorist attack on an Indian army camp in September 2016, when Modi stated that “blood and water and cannot flow together” and vowed to review the treaty.

If Modi is re-elected “there’s a possibility that water may become a tool to try bring Pakistan to heel,” said Ashok Swain, professor of peace and conflict research and the director of research at the School of International Water Cooperation at Uppsala University in Sweden.

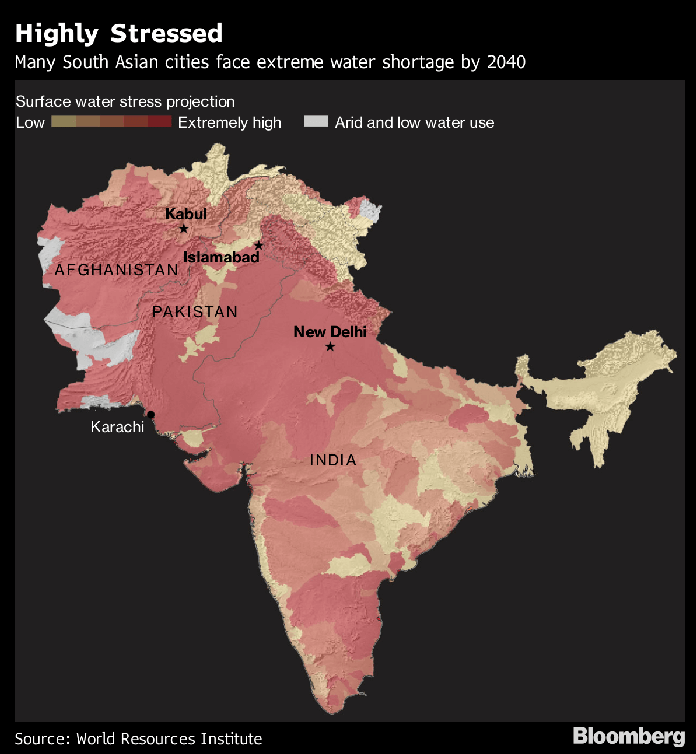

Pakistan, India and Afghanistan are among the world’s eight most water-stressed countries. The Indus river, one of Asia’s longest that originates in the Tibetan Plateau and flows into the Arabian sea near Karachi, has shrunk to a shadow of its former self. Water scarcity has led to regular protests in cities from Shimla in India to Lahore in Pakistan.

Global agencies have made dire predictions that Pakistan — despite having the world’s largest glaciers — will face mass water scarcity by 2025. Already availability per capita has dropped by a third since 1991 to 1,017 cubic meters, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The World Economic Forum rates the water crisis as the biggest risk in Pakistan, with terrorist attacks third on the list. Waseem Akhtar, Karachi’s mayor, told Bloomberg the city needs to fix widespread leakages and theft, but funding is scarce.

Neighbouring India’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply by 2030 and will lead to a six per cent loss in the country’s economic growth by 2050, according to the New Delhi-based government think-tank NITI Aayog.

While a solution will need regional cooperation, there’s been little coordination between India and Pakistan apart from their decades-old river-sharing agreement. Still, officials on both sides of the border recognize they need to act with urgency.