“Those who do not understand the nation’s message will eventually lose,” Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu told thousands of supporters after vote counts revealed that his center-left Republican People’s Party, or CHP, had won the megacity of Istanbul by more than 1 million votes. “Tonight, 16 million Istanbul citizens sent a message to both our rivals and the president,” Reuters reported on April 2 in a dispatch.

The dilemma before the March 31 municipal elections was between status quo and change. With hindsight, one can affirm the event has marked an unprecedented shift in recent Turkish politics. This is not just because the results have led to administrative switches in 29 provinces nationwide but also because this marks a substantial alteration in local power dynamics.

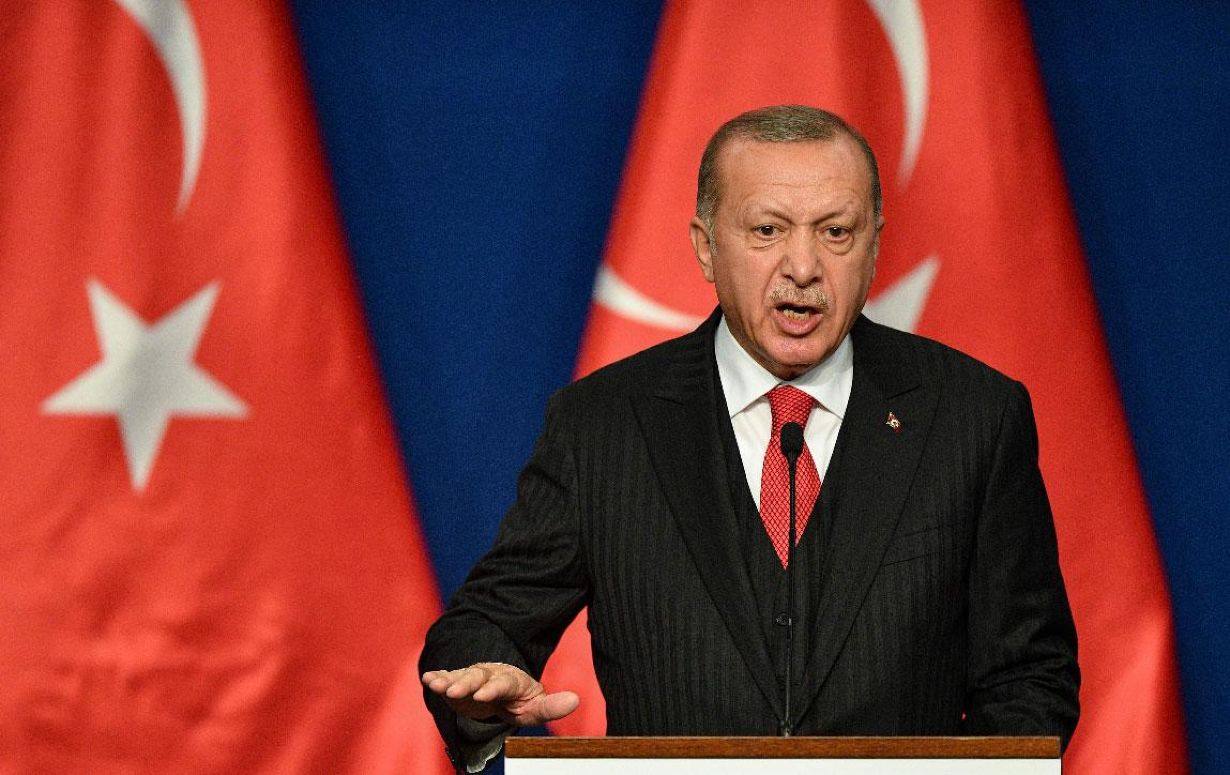

In a speech on Sunday (31 March) night, Erdogan admitted his party had “lost altitude” and would work to rectify its errors. In a diffident tone, he said, “If we made a mistake, we will fix it. If we have anything missing, we will complete it,” he said from the balcony of the presidential palace, according to a Reuter’s translation.

Erdogan, 70, has governed Turkey since 2003. Commenting on the outcome of the 31 March Municipal elections in Turkey, the columnist of CNBC, Natasha Turak, wrote that the sweeping opposition wins in municipal elections across major Turkish cities like Istanbul, Izmir, and the capital Ankara could “set the country in a new direction.”

Erdogan himself rose to prominence as Istanbul’s mayor in the 1990s before going on to win the presidency later; now, analysts are speculating that Mayor Imamoglu’s victory in Istanbul could make him a front-runner for the Turkish presidency in 2028.

Erdogan himself once said that whoever wins Istanbul wins Turkey.

Imamoglu, a 52-year-old former businessman, has been Istanbul’s mayor since 2019. He attempted to run for president in Turkey’s 2023 general election but was banned by Erdogan’s government from running, a move which CHP supporters said was purely political. In those elections, Erdogan’s party won big, leaving the AKP on top at the national level.

Roughly 61 million voters were eligible to cast their votes for mayors, council members, and other administrative leaders across Turkey’s 81 provinces. Voter turnout was registered at 76%, according to the country’s state-run Anadolu news agency. It said CHP came out ahead in 36 of 81 provinces, including several of Turkey’s largest cities.

Why Voters Want A Change

Turkey’s economy has been on a downward graph since 2018, battling severely high inflation, a weak currency, and struggling foreign currency reserves. Annual inflation in the country of 85 million was recorded at 67% for February, and Turkey’s national interest rate sits at 50%—both figures causing significant pain for the ordinary Turkish consumer.

“Disastrous results for the ruling AKP — failing to win major cities and perhaps even losing the national vote to the opposition CHP,” Timothy Ash, senior emerging markets strategist at Bluebag Asset Management, told CNBC. “This result is all about inflation.”

Arda Tunca, an Istanbul-based economist, made a similar assessment. “In 2019, AKP lost major cities owing to the effects of the 2018 [economic] crisis because the crisis was felt mainly in big cities. Now, the threat of impoverishment and unemployment has spread throughout the country,” he said on X.

Turkish Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek was cited by Reuters as saying that the country’s inflation would remain high in the first half of the year “due to base effects and the delayed impact of rate hikes” but that the print would come down in the next 12 months.

Erdogan’s Politics

Undoubtedly, inflation and the economic crisis have been at the center of Erdogan’s party’s municipal election debacle. But other factors contributed to the phenomenon.

With Erdogan not being a direct candidate, AKP’s supporters seemed to have made a distinction between the leader and the party. Despite his indirect candidacy, Erdogan’s highly personalized campaign failed to energize his base, highlighting a desire for political renewal and change.

This might be a consequence of the implementation of the presidential system, which, starting in 2018, has increasingly concentrated power in the hands of the president.

The Turkish voters, known for their strong civil society activism, have become a key force against the country’s drift toward authoritarian rule. By taking action, they have helped create a more balanced political environment, reducing the dominance of any single extreme.

Turkey’s main opposition party, the CHP, responded to its supporters’ wishes for change after numerous electoral losses under Kemal Kilicdaroglu’s leadership. By appointing Ozgür Ozel as the new secretary and elevating the profiles of charismatic mayors like Imamoglu and Ankara’s Mansur Yavas, who oppose Turkey’s shift toward autocracy, the party has made significant strides in appealing to voters.

Various factors have contributed to Erdogan’s party’s debacle in domestic and foreign policy. His autocratic demeanor was evident in the predominantly Kurdish southeast region of Turkey, where the electoral campaign cantered against the practice of appointing government officials in place of mayors who had been officially elected in the previous municipal election.

Erdogan’s non-cooperative role in its capacity as a member of NATO has not gone well with the European members of the organization. Stonewalling the membership of Hungary is an example. Moreover, Erdogan’s soft-paddling with Russia in the Syrian crisis, too, could not be acceptable to the Western powers.

Though elements of Erdoğanism, particularly the political rhetoric used by its supporters, have been inspired by Islamism, the extensive cult of personality surrounding Erdoğan has been argued to have isolated hard-line Islamists who are skeptical of his dominance in state policy.

The central and overarching authority of Erdoğan, a central theme of Erdoğanism, has been criticized by Islamists who believe that the devotion of followers should not be towards a leader but rather to Allah and the teachings of Islam.

As such, the overarching dominance of Erdoğan has furthered Islamist criticism, particularly by Islamist parties such as the Felicity Party (SP), who have claimed that Erdoğanism is not based on Islamism but is instead based on authoritarianism using religious rhetoric to maintain public support amongst conservative supporters.

As a leader schooled in Turkey’s Islamist movement, Erdogan is at his very core an anti-Semite and does not believe in the right of Israel to exist. Instead of standing with Israel in its darkest hour, along with Turkey’s Western allies, Erdogan is choosing to associate with members of the Muslim world, who want to see Israel finished.

- OPED By KN Pandita

- Prof. Pandita (Padma Shri) is the former director of the Center of Central Asian Studies at Kashmir University.

- Views Personal Of The Author.

- Follow EurAsian Times on X (formerly Twitter)